Business Environment and Internal Control Factors (BEICF)

Business Environment and Internal Control Factors (BEICFs) is a regulatory term that denotes the set of tools and information generated internally be a regulated firm to inform is management of Operational Risk. They are one of four elements identified in Basel II, Pillar 1 that AMA institutions must consider in estimating their minimum capital requirement operational risk. The other three are internal loss data, external loss data and scenario analysis. The U.S. Rule for Risk Based Capital Standards: Advanced Capital Adequacy Framework, published in the Federal Register on December 7, 2007, suggests that they are forward-looking indicators of the risk profile. The Basel Framework goes a bit further and discusses them as a way of achieving the “alignment of risk management to capital,” and of providing some “immediacy” in capital estimates. Beyond that however, there appears to be no precise generally accepted regulatory definition of BEICFs yet.

Business Environment and Internal Control Factors (BEICF) are indicators of a bank’s operational risk profile that reflect underlying business risk factors and an assessment of the effectiveness of the internal control environment. They introduce a forward-looking element to an AMA by considering, for example, rate of growth, new product introductions, findings from the challenge process (eg internal audit results), employee turnover and system downtime. Incorporating BEICFs into an AMA helps to ensure that key drivers of operational risk are captured and that a bank’s operational risk capital estimates are sensitive to its changing operational risk profile.[1]

source: Ernst & Young

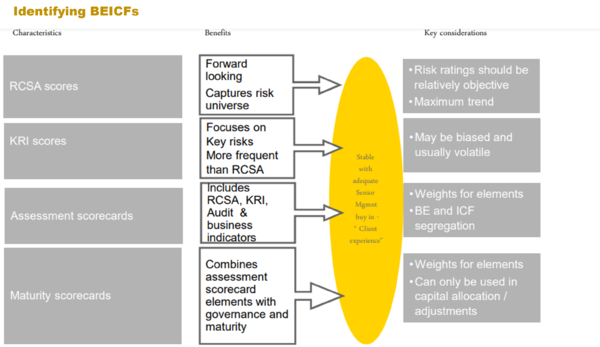

Components of BEICF[2]

- Internal Controls and associated Risk and Control Self Assessments

- Key Risk Indicators / Key Performance Indicators

- Audit Scores / Audit Findings

Industry Positions on BEICF[3]

Position 1: BEICFs are defined as measures that track changes in the operational risk in the business environment and changes in the effectiveness of a firm’s controls.

The environment is defined to include both the internal and external circumstances of the firm’s businesses, and controls are defined as processes that the firm has in place to reduce or eliminate its operational risks. The business environment is the internal and external circumstances of a firm’s businesses that can materially affect its operational risk profile. This includes:

- the quality and availability of the firm’s people, vendors, and other resources;

- the complexity and riskiness of the businesses, the products they deliver and the processes they use to deliver them;

- the degree of automation of the product process and the firm’s capacity for automation;

- the legal and regulatory environment for the businesses; and

- the evolution of the firm’s markets, including the diversity and sophistication of its customers and counterparties, the liquidity of capital markets it trades in and the reliability of the infrastructure that supports those markets.

Internal controls are the detective and preventive processes the firm has in place to reduce the frequency or the severity of operational risk losses or to eliminate altogether the chance of operational risk events. Controls operate by reducing the exposures created by the business environment, by detecting causes, by preventing specific individual risks from arising and by mitigating their effects when they do arise. They can be specific like the confirmation process after a trade or the due diligence before a new hire, or general like a risk and control self assessment process used to detect and assess risks. They can be manual, like the supervisory end-of-day review of a trader’s tickets, partially automatic, like the sign-off often required at certain steps in loan processing by software before the process can proceed, or fully automatic, like many software and building access controls. Controls, however, do not include such things as: insurance – an asset with contingent worth; risk indicators, which may be used in a control but, are not themselves processes; or business processes which contribute directly to the delivery of services to customers. Many risk management processes that support trade-offs of risk and return are not controls. An example might be the use of a screening system that enhances transaction risk management. The system does not enforce a particular behavior so much as enable improved decision making about risk.

Factors are leading measures or indicators of change in the environment or in control effectiveness. Although past losses are an indicator of future losses, loss data are excluded from factors in the context of capital estimation to avoid double-counting, because those data are always taken into account in the other three elements. Otherwise many kinds of objective and subjective measures can be used as factors, including such things as:

- measures of business expansion, such as numbers of new products and increases in gross and net revenues; the number of customer complaints;

- the number of audit points and other measures tracking regulatory and policy compliance and progress in closing any gaps in existing practices;

- outputs from risk and control self assessments, including indicators reflecting the emergence of new risks, the effectiveness of existing controls, control gaps, and progress in closing them; and

- other risk indicators, including general indicators like staff turnover and specific ones like peak capacity utilization in a trading system.

Position 2: BEICFs are more useful for risk management than measurement.

The Basel Framework and U.S. Rule leave the impression that BEICFs are primarily of value in the context of capital estimation. All AMAG member firms believe that the main value of BEICFs is as tools for managing operational risk. Some firms include BEICFs in risk reporting on changing conditions and control effectiveness; use them to set thresholds determined by policy; to benchmark one unit’s performance against

another’s; to define triggers for escalation; and in balanced scorecards for performance evaluation. Firms use BEICFs to characterize and report on the dynamics of the business environment and on the state of their internal controls. BEICFs add value in risk management by providing definition and specificity to policy on risk appetite and tolerance, and by prompting line manager responses to signals of critical changes in the business

environment and internal control effectiveness. Investment in the development of additional BEICFs should usually be driven by where they are likely to make the largest impact on management, as opposed to capital estimation.

Position 3: Firms need flexibility to tailor their choice of BEICFs, depending on availability, applicability, usefulness, purpose and integration.

Availability and applicability of BEICFs will depend on such things as the business profile, process architecture, degree of automation and the rate of change in external circumstances – in other words, the business environment. The usefulness of individual measures will depend on: the level in the organization of the manager who is using them; the risk appetite and tolerance of the organization; the management style; and the relevance of available measures to understanding the business environment and controls. In reporting, the usefulness will also depend on the extent to which measures are supplemented by descriptive information and analysis on, for example, causality. A firm's choice of BEICFs will also depend on the purpose for which they are being used and the manner in which they are integrated into the AMA framework. This includes how they are included in the management reporting process, and whether they are used as a direct or indirect input (the latter, typically through scenario analysis) into the capital model. Other important considerations include providing information that is useful for line of business risk management, appropriately balancing effectiveness with efficiency, and leveraging existing sources of information.

Position 4: BEICFs should play a secondary role in capital estimation.

If it is ever possible to establish significant statistical relationships with future loss distributions, BEICFs may become more useful in capital estimation. Until then, their use should remain secondary to internal and external loss data and scenario analysis. For capital estimation, they should be an input into scenario analysis or into a global adjustment to a calculated capital estimate reflecting considerations not otherwise taken into account. In the latter case, it may well make sense to continue the current practice of the majority of AMAG firms and limit their overall effect to an increase or a decrease of some specified amount such as 5%, 10%, 20% or 30%.

See Also