Difference between revisions of "Cost Effectiveness Analysis (CEA)"

| Line 11: | Line 11: | ||

Cost-effectiveness analysis (CEA) considers alternatives in reference to the ratio between the costs associated with each alternative and a single quantified, but not monetary, effectiveness measure. This represents a complication of CEA as costs are represented by monetary values, while effectiveness may be measured in terms of saved lives, time savings or other similar quantifiable measures. For this reason, in CEA a ratio is calculated. | Cost-effectiveness analysis (CEA) considers alternatives in reference to the ratio between the costs associated with each alternative and a single quantified, but not monetary, effectiveness measure. This represents a complication of CEA as costs are represented by monetary values, while effectiveness may be measured in terms of saved lives, time savings or other similar quantifiable measures. For this reason, in CEA a ratio is calculated. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | === Explaining Cost Effectiveness Analysis (CEA)<ref>Explaining Cost Effectiveness Analysis (CEA) [https://www.betterevaluation.org/en/evaluation-options/CostEffectivenessAnalysis BetterEvaluation]</ref> === | ||

| + | CEA is most useful when analysts face constraints which prevent them from conducting cost-benefit analysis. The most common constraint is the inability of analysts to monetize benefits. CEA is commonly used in healthcare, for example, where it is difficult to put a value on outcomes, but where outcomes themselves can be counted and compared, e.g. ‘the number of lives saved’. | ||

| + | |||

| + | CEA measures costs in a common monetary value (££) and the effectiveness of an option in terms of physical units. Because the two are incommensurable, they cannot be added or subtracted to obtain a single criterion measure. One can only compute the ratio of costs to effectiveness in the following ways: | ||

| + | |||

| + | CE ratio = C1/E1 | ||

| + | |||

| + | EC ratio = E1/C1 | ||

| + | |||

| + | where: C1 = the cost of option 1 (in £); and E1 = the effectiveness of option 1 (in physical units). | ||

| + | |||

| + | The first equation above represents the cost per unit of effectiveness (e.g. £s spent per life saved). Projects can be rank ordered by CE ratio from lowest to highest. The most cost-effective project has the lowest CE ratio. The second equation is the effectiveness per unit of cost (e.g. lives saved per £ spent). Projects should be ranked from highest to lowest EC ratios. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The outputs to be ranked by cost-effectiveness analysis will often be social or environmental in nature. For example, work in health economics looking at the cost-effectiveness of different treatments. As with CBA, the level of detail for the analysis will typically depend on the specific issue being addressed, but should take a broad view of costs and benefits to reflect all stakeholders. | ||

| Line 47: | Line 63: | ||

Cost-effectiveness analysis is not always feasible, in which case spending might be directed towards more cost-effective interventions instead. However, if done correctly, this process can provide valuable insights into how best to allocate resources in order to achieve the greatest impact possible. | Cost-effectiveness analysis is not always feasible, in which case spending might be directed towards more cost-effective interventions instead. However, if done correctly, this process can provide valuable insights into how best to allocate resources in order to achieve the greatest impact possible. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | == How to do Cost Effectiveness Analysis<ref>How to do a basic cost-effectiveness analysis [https://tools4dev.org/resources/how-to-do-a-basic-cost-effectiveness-analysis/ Tools4dev]</ref> == | ||

| + | *Decide which outcome you will use for the comparison: The first step is to decide which outcome you will use to compare the activities. It needs to be the same outcome for both activities so you are comparing apples with apples. It also needs to be something you can measure accurately. For example, the number of toilets built, the number of small businesses set up, the number of trees planted, or the number of children who don’t drop out of school. Make sure you clearly define how the outcome is measured. For example, if it is the number of pregnant women attending antenatal care, then how many visits do they need to attend? What if they only attend some visits? Or don’t complete all the required steps? The outcome needs to be measured the same way every time. | ||

| + | *Measure the outcome: If you are comparing the cost effectiveness for two activities then you need to measure the outcome in question for both activities. Let’s continue with the antenatal visit example. Say you want to compare one-on-one outreach with mass SMS messages. First you would need one group of pregnant women who don’t receive any intervention, and you would count how many of them attend antenatal care. For example, 25 women out of a group of 100. Then you would need a second group of pregnant women who receive one-on-one outreach visits. Count how many of them attend antenatal care – let’s say it’s 42 women out of a group of 100. Then subtract how many attended from the first group (42-25 = 17). That means the one-on-one outreach resulted in 17 extra women attending antenatal care. You also need a third group of women who receive SMS messages reminding them to attend antenatal care. Count how many of them attended. Let’s imagine that it was 31. Subtract the number who attended in the first group (31-25=6), meaning that 6 extra women attended antenatal care as a result of receiving the SMS. | ||

| + | *Calculate the costs: The next step is to work out how much each activity cost. Make sure you take into account every cost associated with the activity, including the cost of the time that staff spend organizing and implementing it. Keeping with the same example, this would mean adding up all the costs for the one-on-one outreach sessions, then separately adding up all the costs for the SMS messaging. Let’s say that the total cost of the one-on-one outreach for 100 women was $3,500 and the total cost of the SMS messages was $700. | ||

| + | *Divide the cost by the outcome for each activity: To calculate the cost-effectiveness for each activity divide the total costs by the outcome. In this example that means dividing the total cost of one-on-one outreach or SMS messages by the total number of extra pregnant women who attended antenatal care. In this fictitious example, SMS messages are more cost effective that one-on-one outreach when it comes to getting women to attend antenatal care. | ||

| + | |||

| + | '''Limitations of this method'''<br /> | ||

| + | This is a very basic method for doing cost-effectiveness analysis. It is useful when you want to compare different activities that have exactly the same outcome in order to save money. However, it’s important to realize the limitations. Cost-effectiveness analysis only looks at one outcome. In this example it was the number of women attending antenatal care. It doesn’t take into consideration other factors. | ||

| + | |||

| + | For example, it’s possible that one-on-one outreach had other benefits for vulnerable women (emotional support or increased knowledge of good childcare practices) which were not provided by the SMS messages. One-on-one outreach also achieved a higher participation in antenatal care, so if you wanted the maximum number of women to attend it might still be a better choice. | ||

| + | |||

| + | There may also be times when it is difficult to accurately measure the costs or outcomes of a particular activity. This is often the case when multiple activities are integrated into one program, and there aren’t separate groups of people receiving different activities. In this case cost-effectiveness analysis may not be appropriate. | ||

Revision as of 17:26, 14 June 2022

What is Cost Effectiveness Analysis (CEA)

Cost-effectiveness analysis (CEA) is a decision-making tool that helps compare different ways to achieve a goal in terms of their resource utilization (cost) and outcomes (effectiveness). It can be used to find the cheapest way to achieve a goal, or to estimate the expected costs of achieving a particular outcome. It can also be used to compare the impacts and cost of various alternative means of achieving the same objective. The result of a CEA is expressed in a ratio (cost-effectiveness ratio, CER) between cost and outcome.

Understanding Cost Effectiveness Analysis (CEA)[1]

The best cost-effectiveness analyses take a broad view of costs and benefits, including indirect and longer-term effects, reflecting the interests of all stakeholders who will be affected by the program. So make sure the analysis is as comprehensive as possible.

The concept of cost-effectiveness is applied to the planning and management of many types of organized activity. It is widely used in many aspects of life. In the acquisition of military tanks, for example, competing designs are compared not only for a purchase price, but also for such factors as their operating radius, top speed, the rate of fire, armor protection, and caliber and armor penetration of their guns. If a tank’s performance in these areas is equal or even slightly inferior to its competitor, but substantially less expensive and easier to produce, military planners may select it as more cost effective than the competitor.

Cost-effectiveness analysis is not uniformly applied in the healthcare system. Decision makers often adopt new treatments without knowing if they are cost-effective. Even when cost-effectiveness has been studied, decision-makers may not be able to interpret the data, or they may not agree with the results. Despite this limitation, cost-effectiveness is increasingly used to inform healthcare decision makers.

Cost-effectiveness analysis (CEA) considers alternatives in reference to the ratio between the costs associated with each alternative and a single quantified, but not monetary, effectiveness measure. This represents a complication of CEA as costs are represented by monetary values, while effectiveness may be measured in terms of saved lives, time savings or other similar quantifiable measures. For this reason, in CEA a ratio is calculated.

Explaining Cost Effectiveness Analysis (CEA)[2]

CEA is most useful when analysts face constraints which prevent them from conducting cost-benefit analysis. The most common constraint is the inability of analysts to monetize benefits. CEA is commonly used in healthcare, for example, where it is difficult to put a value on outcomes, but where outcomes themselves can be counted and compared, e.g. ‘the number of lives saved’.

CEA measures costs in a common monetary value (££) and the effectiveness of an option in terms of physical units. Because the two are incommensurable, they cannot be added or subtracted to obtain a single criterion measure. One can only compute the ratio of costs to effectiveness in the following ways:

CE ratio = C1/E1

EC ratio = E1/C1

where: C1 = the cost of option 1 (in £); and E1 = the effectiveness of option 1 (in physical units).

The first equation above represents the cost per unit of effectiveness (e.g. £s spent per life saved). Projects can be rank ordered by CE ratio from lowest to highest. The most cost-effective project has the lowest CE ratio. The second equation is the effectiveness per unit of cost (e.g. lives saved per £ spent). Projects should be ranked from highest to lowest EC ratios.

The outputs to be ranked by cost-effectiveness analysis will often be social or environmental in nature. For example, work in health economics looking at the cost-effectiveness of different treatments. As with CBA, the level of detail for the analysis will typically depend on the specific issue being addressed, but should take a broad view of costs and benefits to reflect all stakeholders.

Cost-effectiveness analysis (CEA) vs. Cost-benefit analysis (CBA)

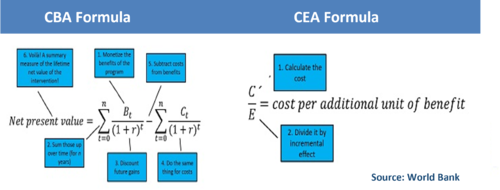

There are a few key differences between cost-benefit analysis (CBA) and cost-effectiveness analysis (CEA). CBA measures the monetary value of all costs to all benefits, whereas CEA only calculates costs to outcomes of interest. This means that CBA is useful for making cross-comparative decisions across vastly different interventions (i.e., agriculture versus education), while CEA is used for comparing programs with common outcome(s) in mind, or when using nonmonetary values as well as monetary values are relevant to decision-making purposes.

CEA is more rigorous and in-depth than CBA, but it assumes a specific post-intervention trajectory. In contrast, CBA does not make any assumptions about the future and can be used for both pre- and post-intervention comparisons. Another important distinction is that while CBAs require a number of assumptions about the monetary values of all benefits, CEAs are transparent, simple and objective. Finally, while CBA measures the monetary value of all costs to all benefits, CEA only calculates costs to outcomes of interest.

While CBAs provide more information than CEAs about potential outcomes after an intervention, they are less able to calculate the cost of an intervention with respect to its benefits or effectiveness only. In contrast, CEAs are able to calculate the cost of an intervention with respect to its benefits or effectiveness only and can provide more detailed information about potential outcomes after an intervention.

When making decisions about which interventions to pursue, it is important to consider both CBA and CEA. However, given that CEAs are more rigorous and in-depth than CBAs, they should be used when there is a specific post-intervention trajectory in mind or when nonmonetary values as well as monetary values are relevant to decision-making purposes.

CBA calculates the monetary ratio of all costs to all benefits of a program. CBA can help to determine whether a program is worth the investment. It can also allow comparison across vastly different interventions (i.e. education versus agriculture). However, CBA requires a number of strong assumptions about the monetary value of all the different benefits, including the lifetime benefits of an intervention. In contrast, CEA is a transparent, simple, and objective measurement that enables comparison of programs with common outcome(s) of interest. However, the implicit assumption is a common post-intervention trajectory.

Considerations for cost calculations[3]

- Use program financial records. Typically, begin calculating costs by referring to program budgets, which provide a list of all relevant activities involved in implementing the program. Consider, however, that budgets are forward-looking estimates of true costs. Thus, it’s better to use actual program financial records on expenditures for calculations. However, this is not commonly done.

- Interview program and field staff to get key information including unit cost data like allocation of staff time across activities and wages for staff at various levels of implementation team. Note that using average wages makes calculations less sensitive.

- Model program costs at the margin. You want to capture marginal costs of new activities initiated as part of the interventions. For example, to calculate the costs of a school meals program, you may need the cost of new kitchen, cooks, implements, and food. However, you should not include the cost of school administration or buildings as these would exist whether or not the intervention was implemented.

- Consider depreciation. Account for how to value new assets or equipment obtained over the program implementation period.

- Consider the cost of user time. Include the costs of participation in program (i.e. using local wages).

- Differentiate between pilot costs and scale-up costs.

- Include spillover effects on indirect beneficiaries when quantifying impacts

Why Use Cost-Effectiveness Analysis?

There are many reasons why an organization might want to use cost-effectiveness analysis. Perhaps the most important reason is that it allows organizations to identify low-cost, high-impact interventions. For example, each year more than a million young children die from dehydration when they become ill with diarrhea. However, oral rehydration therapy is a way of treating diarrhea that does not diminish its severity or mortality rate. Oral rehydration therapy cost only $2-$4 per life year saved and was promoted by public policy to help save millions of lives worldwide .

Another reason for using cost-effectiveness analysis is that it helps identify where to allocate resources in order to maximize impact. A study at Harvard University focused on the 185 interventions which cost US$21 each year . This type of analysis can help countries make decisions about which interventions are most effective and allocation of funds.

Cost-effectiveness analysis is not always feasible, in which case spending might be directed towards more cost-effective interventions instead. However, if done correctly, this process can provide valuable insights into how best to allocate resources in order to achieve the greatest impact possible.

How to do Cost Effectiveness Analysis[4]

- Decide which outcome you will use for the comparison: The first step is to decide which outcome you will use to compare the activities. It needs to be the same outcome for both activities so you are comparing apples with apples. It also needs to be something you can measure accurately. For example, the number of toilets built, the number of small businesses set up, the number of trees planted, or the number of children who don’t drop out of school. Make sure you clearly define how the outcome is measured. For example, if it is the number of pregnant women attending antenatal care, then how many visits do they need to attend? What if they only attend some visits? Or don’t complete all the required steps? The outcome needs to be measured the same way every time.

- Measure the outcome: If you are comparing the cost effectiveness for two activities then you need to measure the outcome in question for both activities. Let’s continue with the antenatal visit example. Say you want to compare one-on-one outreach with mass SMS messages. First you would need one group of pregnant women who don’t receive any intervention, and you would count how many of them attend antenatal care. For example, 25 women out of a group of 100. Then you would need a second group of pregnant women who receive one-on-one outreach visits. Count how many of them attend antenatal care – let’s say it’s 42 women out of a group of 100. Then subtract how many attended from the first group (42-25 = 17). That means the one-on-one outreach resulted in 17 extra women attending antenatal care. You also need a third group of women who receive SMS messages reminding them to attend antenatal care. Count how many of them attended. Let’s imagine that it was 31. Subtract the number who attended in the first group (31-25=6), meaning that 6 extra women attended antenatal care as a result of receiving the SMS.

- Calculate the costs: The next step is to work out how much each activity cost. Make sure you take into account every cost associated with the activity, including the cost of the time that staff spend organizing and implementing it. Keeping with the same example, this would mean adding up all the costs for the one-on-one outreach sessions, then separately adding up all the costs for the SMS messaging. Let’s say that the total cost of the one-on-one outreach for 100 women was $3,500 and the total cost of the SMS messages was $700.

- Divide the cost by the outcome for each activity: To calculate the cost-effectiveness for each activity divide the total costs by the outcome. In this example that means dividing the total cost of one-on-one outreach or SMS messages by the total number of extra pregnant women who attended antenatal care. In this fictitious example, SMS messages are more cost effective that one-on-one outreach when it comes to getting women to attend antenatal care.

Limitations of this method

This is a very basic method for doing cost-effectiveness analysis. It is useful when you want to compare different activities that have exactly the same outcome in order to save money. However, it’s important to realize the limitations. Cost-effectiveness analysis only looks at one outcome. In this example it was the number of women attending antenatal care. It doesn’t take into consideration other factors.

For example, it’s possible that one-on-one outreach had other benefits for vulnerable women (emotional support or increased knowledge of good childcare practices) which were not provided by the SMS messages. One-on-one outreach also achieved a higher participation in antenatal care, so if you wanted the maximum number of women to attend it might still be a better choice.

There may also be times when it is difficult to accurately measure the costs or outcomes of a particular activity. This is often the case when multiple activities are integrated into one program, and there aren’t separate groups of people receiving different activities. In this case cost-effectiveness analysis may not be appropriate.

Applications of CEA[5]

The concept of cost-effectiveness is applied to the planning and management of many types of organized activity. It is widely used in many aspects of life. In the acquisition of military tanks, for example, competing designs are compared not only for purchase price, but also for such factors as their operating radius, top speed, rate of fire, armor protection, and caliber and armor penetration of their guns. If a tank's performance in these areas is equal or even slightly inferior to its competitor, but substantially less expensive and easier to produce, military planners may select it as more cost-effective than the competitor.

Conversely, if the difference in price is near zero, but the more costly competitor would convey an enormous battlefield advantage through special ammunition, radar fire control and laser range finding, enabling it to destroy enemy tanks accurately at extreme ranges, military planners may choose it instead – based on the same cost-effectiveness principle.

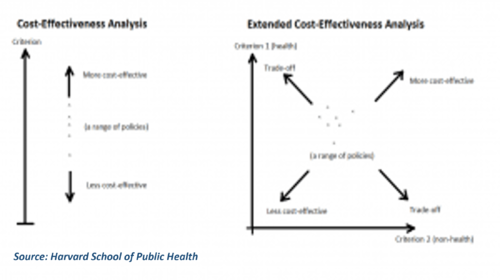

Extended Cost-Effectiveness Analysis (ECEA)[6]

Extended Cost-Effectiveness Analysis (ECEA) is a form of quantitative economic analysis that assesses the health and financial impact of health policies. It is an expansion of cost-effectiveness analysis, which compares the relative costs and gains in health outcomes (in the form of years of life saved, premature deaths averted, quality- or disability-adjusted life years gained/averted, etc.) of interventions. ECEA also includes non-health benefits such as financial risk protection and distributional consequences like equity in the economic evaluation of health policies. This enables health policy makers to take into account multiple criteria and make trade-offs among competing demands (see Figure below).

Challenges to conducting CEA

It is no secret that conducting a Cost-Effectiveness Analysis (CEA) can be difficult. In fact, many challenges exist when trying to measure the cost of an intervention and its impact on a single outcome. For one, it can be hard to obtain accurate cost estimates from other sources. This is due in part to exchange rates, inflation rates, and discount rates- which make comparisons between studies or programs difficult.

Another challenge faced when conducting CEA is that they often take a long time to complete. Aggregating across multiple outcomes also proves to be difficult- especially when trying to measure costs over different time periods.

Despite these challenges, there are some considerations for how to calculate costs that researchers must take into account. These include research methods, economic assumptions, and what impacts you want to measure/costs over which time periods/etc..

One exception where CEA has been used in the past is with "National recommendations on immunization policy." The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices uses Cost-Effectiveness Analysis as a tool when making national recommendations about immunizations.

However, using CEA evidence for health care decisions is not uncontroversial in America. Many people are resistant to the idea of accepting limits on the delivery of health care. This may be partly due to a lack of understanding about what rationing would entail and how it would affect them personally. However, conducting CEA remains an important tool in assessing the value of health technology. Methods have been improved over time, but there is still room for growth in this area.

Ethical Considerations for CEA[7]

There have been a few criticisms on ethical grounds of CEA’s use for decision making. These include:

- Controversies associated with the use of QALYs: The lower health utility, or health-related quality of life, assigned to patients with worse health (because of more severe disease, disability, age, and so on) raises distributional issues in using QALYs for resource allocation decisions. For example, because patients with disabilities have a lower overall health utility weight, any extension of their lives by reducing the health burden from one disease “would not generate as many QALYs as a similar extension of life for otherwise healthy people.” This distributional limitation arises because of the multiplicative nature of QALYs, which are a product of life-years and health utility weight. Consequently, the National Council on Disability has strongly denounced the use of QALYs. Alternatives to QALYs have been proposed. The Institute for Clinical and Economic Review has started using the equal value of life-years gained metric, a modified version of the equal value of life (EVL) metric, to supplement QALYs. In EVL calculations, any life-year gained is valued at a weight of 1 QALY, irrespective of individuals’ health status during the extra year. EVL, however, “has had limited traction among academics and decision-making bodies” because it undervalues interventions that extend life-years by the same amount as other interventions but that substantially improve quality of life.30 More recently, a health-years-in-total metric was proposed to overcome the limitations of both QALYs and EVL, but more work is needed to fully understand its theoretical foundations.

- Distributive justice. The second criticism pertains to the fundamental notion that “a QALY is a QALY is a QALY no matter who gets it.” Because of this egalitarian notion, the question of whose values shall count for how much raises some ethical issues. For example, should large benefits to a small number of people receive priority over smaller but greater aggregate benefits to a large number of people? Or when should society give priority to treating the sickest or worst off? However, CEA was not meant to address such distributional considerations directly. The Second Panel on Cost-Effectiveness in Health and Medicine emphasized that such distributive considerations also matter to decision makers and are often part of deliberative processes. Areas of ongoing research include the development of equity weights, which assign numerical values based on considerations other than QALYs (eg, the severity or rarity of the disease), and incorporating social distributions of health (eg, by income or ethnicity) into CEA.

- Incomplete valuation. The third criticism relates to CEA’s consideration (or lack thereof) of certain value elements. Many HTA bodies around the world use CEA from a health care sector perspective and do not incorporate value elements such as productivity, time costs, caregivers’ costs, and spillover to other sectors of the society. Even in the United States, ICER has not considered these elements formally, although more recently it has allowed for a modified societal perspective as a secondary analysis.7 The Second Panel on Cost-Effectiveness in Health and Medicine, which recommends analyses using both the health care sector perspective and the societal perspective, has laid out the methods for incorporating such value elements. Often, lack of data (eg, the effect of a treatment on productive time) precludes analysts from including some of these value elements in the analysis, even though they are generally believed to be important to patients and their caregivers. Although recent advances in measuring these value elements have provided a set of useful resources, more work is needed to readily incorporate these elements into standard CEA.

While the criticisms have been discussed in detail here, it is worth pointing out that cost-effectiveness evidence is only one of many factors considered in resource allocation decisions. It has been found that none of the international HTA bodies bases its decisions solely on cost-effectiveness evidence. Therefore, much of CEA’s criticisms, fair or not, can be addressed through deliberative processes.

See Also

References

- ↑ Understanding Cost Effectiveness Analysis (CEA) MSR

- ↑ Explaining Cost Effectiveness Analysis (CEA) BetterEvaluation

- ↑ Considerations for cost calculations World Bank

- ↑ How to do a basic cost-effectiveness analysis Tools4dev

- ↑ Applications of CEA Wikipedia

- ↑ What is Extended Cost-Effectiveness Analysis (ECEA)? HSPH

- ↑ Ethical Considerations for CEA David D. Kim, PhD and Anirban Basu, PhD