Difference between revisions of "First Principles Thinking"

| Line 31: | Line 31: | ||

Every question peels a layer off until you find out an episode in the childhood where that reaction was born. It is a powerful way of thinking. Once you make it a habit, you will learn to apply it in other areas of your life. | Every question peels a layer off until you find out an episode in the childhood where that reaction was born. It is a powerful way of thinking. Once you make it a habit, you will learn to apply it in other areas of your life. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | '''First Principle in Business<ref>First Principle and Business Development | ||

| + | The first thing you need to realize when trying to improve something from a first principle perspective, is that change is hard. Compare it to getting out of bed at 3.00 AM. It is not impossible to do it once or twice, but hard when it is more frequent. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Companies experience a similar issue with change. The mantra when things are going well can be summarized in “if it ain’t broke, don’t fix it”. Companies that experience that, get quickly rusted into habits, making change an unpopular priority. Even when change seems, in both foresight and hindsight, necessary. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Proof of that is the many retail shops that have closed in neighborhoods because they failed to embrace e-commerce on time. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The second thing you need to understand is that first principle follows a similar process as critical thinking or scientific reasoning. It follows the process of questioning, reflecting and coming with fundamental assumptions. | ||

| + | |||

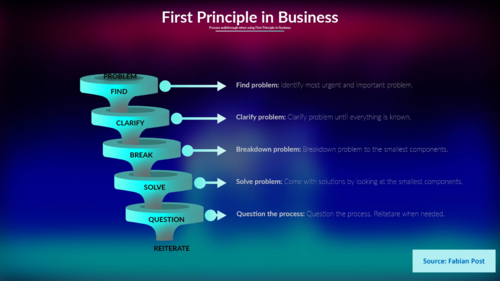

| + | For the next part, the Socratic questioning has been adapted to create a model you can use (see figure below). It should guide you to apply first principle thinking in business scenarios you deem necessary. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | [[File:First Principle in Business.png|500px|First Principle in Business.png]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | The model compromises of five parts: | ||

| + | *Finding problem: As with anything related to business, you need to first identify a problem. Problems can be something encountered organically in a company, but it can also not be as clear or pressing. For example, figuring out how to become less dependable of a client or secure continuity are problems that can be deep and require reflection. However, both may not be urgent nor important depending on the risk threshold a company adopts. Questions that you can ask during this phase, should be about identifying the problem. Though, it may seem that finding the problem is enough, you should also investigate the feasibility of the solution. This will save time when it comes to the reiterative process, which can quickly become cumbersome when an irresolvable problem arises at a later stage. You can refer this stage also as the what stage. You do not necessarily have to adhere only to what questions, but it functions as a rule of thumb. Some example questions you can ask and reflect on are the following: | ||

| + | **What problems are urgent? | ||

| + | **What problems are important? | ||

| + | **What problems are both urgent and important? | ||

| + | **What other problems are both urgent and important? | ||

| + | **How can you verify or disprove whether it is a problem? | ||

| + | **What problems affect the company now? | ||

| + | **What problems will affect the company in the future? | ||

| + | **What are our competitors doing that may cause a problem in the future? | ||

| + | **What problems affect customers? | ||

| + | **What problems will affect our clients in the future? | ||

| + | **What problems affect staff? | ||

| + | **What problems will affect staff in the future? | ||

| + | **What problems affect other stakeholders? | ||

| + | **What other problems are similar in nature? | ||

| + | **How do we know that the problem is a problem? | ||

| + | **Why do we think solving the problem is worth the capital? | ||

| + | **Is the problem solvable? | ||

| + | **How is the problem solvable? | ||

| + | *Clarifying problem: Now that you have identified at least one problem, it is time to clarify the problem. Clarification will help in breaking down the problem to the most essential components. Moreover, it helps in structuring and framing the solutions at the end. When you clarify a problem, you will want to know exactly what the problem is and how it came to be. It is during this part that you also challenge the problem. If the problem happens to not be a problem, you need to go back to step one or grab the second problem you came across and forego the clarification process once more. Similar as before, you could define this stage as the how stage. Example questions could be: | ||

| + | **Why is it a problem? | ||

| + | **What do we know about the problem? | ||

| + | **What do we not know about the problem? | ||

| + | **What are the blind spots to the problem? | ||

| + | **How do we know about the blind spots? | ||

| + | **Why is solving the problem important? | ||

| + | **How can we look differently at the problem? | ||

| + | **How do the different divisions view the problem? | ||

| + | **How do customers view the problem? | ||

| + | **How do different stakeholders view the problem? | ||

| + | **What other explanations are there for the problem? | ||

| + | **What effect does the problem have on the business? | ||

| + | **Why does the problem affect the business? | ||

| + | **Why does the problem affect customers? | ||

| + | **What is true about the problem? | ||

| + | **How do we know that the problem is true? | ||

| + | **What is causing the problem? | ||

| + | **What are the counter arguments for the problem? | ||

| + | *Break down problem: Breaking the problem down allows you to look at the fundamental elements of the problem. Elements that if taken apart will give you a better idea of how to work things out. Think of it like a Lego construction. Taking pieces apart one by one, will yield building blocks (fundamental elements) that allows you to build something new. However, before doing so, you will need to make sure to create a blueprint of the current construction (continuing with the Lego example). Take the construction apart. Look at all the elements. Once you have done that you can go to the next stage to see whether you can improve the blueprint, create a complete new-one, demolish it and so on. During this stage a reward assessment is important. The way you could assess that is by asking three different questions. What happens if you do something, if you do not and if you ignore it. Needless to say, if nothing happens with all three scenarios you will need to go back to a different problem and reiterate. | ||

| + | As with the two previous stages, this is referred to as the why stage. Like before, this is not necessary to frame the question, but a why question digs deeper and breaks down the problem to the point where we cannot explain things further. Questions that can help you through are below, remember to ask why after each question: | ||

| + | **What is the essential part of the problem? | ||

| + | **What do we believe is the smallest part of the problem? | ||

| + | **How do we know what the smallest part of the problem is? | ||

| + | **What other components are there to the problem? | ||

| + | **Where does the problem originate? | ||

| + | **What is the blue-print of the problem? | ||

| + | **How can we test the problem? | ||

| + | **Which divisions are hindered by the problem? | ||

| + | **What conflict of interest is there with the problem? | ||

| + | **What ways does solving the problem help the business? | ||

| + | **What are the implications? | ||

| + | **What are the consequences? | ||

| + | **What happens if we do not act on the problem? | ||

| + | **What happens if we ignore the problem? | ||

| + | **happens if we do act on the problem? | ||

| + | *Solve problem: Now that you know what the problem is, how it affects the company, why the problem even exists and what part is exactly responsible for it, it is time to solve the problem. Continuing the analogy of before, with Lego. By taking apart the building blocks, you can use them to build something new. It may sound cryptic, but once you break things apart and look at the individual components, you should have the necessary information to solve the problem. During this phase it is important to come-up with different solutions and pit them against each other. Moreover, the solutions should be put into contrast with what the company can do and deliver. Lastly, it should be clear who is responsible for solving the problem and when the results should be seen. Some helpful questions would include: | ||

| + | **How can we solve the problem? | ||

| + | **What other solutions are there to the problem? | ||

| + | **Why is one solution better than the other? | ||

| + | **How does solving the problem affect the business? | ||

| + | **How does the solution benefit the business? | ||

| + | **What is the most important part to solve the problem? | ||

| + | **How do we know that the solution solves the problem? | ||

| + | **What do we have to solve the problem? | ||

| + | **What do we need to solve the problem? | ||

| + | **How does solving the problem affect the finances of the company? | ||

| + | **How is the investment worth solving the problem? | ||

| + | **What do we need to invest to solve the problem? | ||

| + | **What other problems does the solution solve? | ||

| + | **What other problems does the solution create? | ||

| + | **How does the solution affect all stakeholders? | ||

| + | **What happens if we cannot solve the problem? | ||

| + | **What can we learn after solving the problem? | ||

| + | **What knowledge and insights can we use to solve other problems? | ||

| + | **What steps are necessary to solve the problem? | ||

| + | **Who will be responsible for leading the solution to the problem? | ||

| + | **Who will monitor and evaluate? | ||

| + | **How do we measure solving the problem? | ||

| + | **Which solution is the team going to pursue? | ||

| + | **When is the solution going to be implemented? | ||

| + | *Question the questions: The last part is reviewing the total process you have gone through. You can question any of the previous phases and see if you have covered things that has not occurred before. During this stage, it is important to question the process, problem, clarification, break down and solution. If improvements need to be made, reiterate. If everything seems water proof, you can conclude and execute. | ||

| + | Despite how rational it sounds to think from first principle, it is not always the best way to go about problems. Companies are generally entities that are already efficient. Some companies or departments will undoubtedly be more efficient than others, but there are always tradeoffs when approaching things from first principle. Moreover, using first principle does not always yield positive or efficient results. Questioning everything (why) can sometimes result in unsatisfactory answers, wherein a company can conclude there is not much they can do about a problem. Furthermore, if that type of thinking is incorporated in a company without consequences, it can lead to a company that experiences the dreadful analysis paralysis. | ||

Revision as of 19:30, 13 June 2022

First-principles thinking is one of the best ways to reverse-engineer complicated problems and unleash creative possibility. Sometimes called “reasoning from first principles,” the idea is to break down complicated problems into basic elements and then reassemble them from the ground up. It’s one of the best ways to learn to think for yourself, unlock your creative potential, and move from linear to non-linear results. This approach was used by the philosopher Aristotle and is used now by Elon Musk and Charlie Munger. It allows them to cut through the fog of shoddy reasoning and inadequate analogies to see opportunities that others miss.[1]

First Principles Frameworks[2]

Here are three frameworks that will help you to start practicing thinking from First Principles.

1. Socratic Questioning

- Clarifying your thinking and explaining the origins of your ideas. Why do I think this? What exactly do I think?

- Challenging assumptions. How do I know this is true? What if I thought the opposite?

- Look for evidence. Why do I think this is true? What are the sources?

- Consider alternative perspectives. What might others think? How do I know I am correct?

- Examine the consequences and implications. What if I am wrong? What are the consequences if I am?

- Question the original questions. Why did I think that? Was I correct? What conclusions can I draw from the reasoning process?

It helps to figure out several important things. First, find the origins of your idea. Is it based on your assumptions? Can you find data to prove its viability? Second, consider symmetrically different perspectives to understand possible consequences. Lastly, conclude and move up from there.

2. Elon Musk's First Principle Reasoning Framework Elon Musk was one of the first to popularize reasoning from first principles. This approach led him to discover opportunities for his new companies SpaceX and Tesla, which made him the richest person in the world in 2021. It was not until Elon started up SpaceX when the whole aerospace industry shifted. Before, every company took an approach of incremental change and improvement before his intervention. The existing technologies have been improved and tinkered with since the mid of the 20th century. To gain insight, he asked the following questions.

- What are the problems?

- Why is it expensive?

- What can I do differently?

- What do we know is true?

- What are the obstacles?

Nobody assumed to reduce the cost of rocket production and launches. First principles reasoning led him to discover that production cost can be significantly reduced. He deconstructed the problem into its foundational principles and built his solution from the bottom up. Elon Musk's 3-step framework

- Identify current assumptions.

- Break down the problem into its fundamental principles.

- Create new solutions from the discovered truth.

This framework provides a solid structure to deconstruct a problem and test different solutions. If you have an idea, try to apply Elon's framework to gain insight and find secrets that thinking by analogy would not allow.

3. Five Whys Framework Children naturally think in first principles. They ask questions until they get to the bottom of it and understand the foundations. It is essential to align the knowledge of the world with reality as closely as possible. Wrong assumptions could threaten the chances of survival in the past. Unfortunately, most of the parents get annoyed by constant questioning. They either do not know the proper answer or think that a child can not understand the complexity of the world. Therefore, the most popular answer among parents is "Because I said so".

Every question peels a layer off until you find out an episode in the childhood where that reaction was born. It is a powerful way of thinking. Once you make it a habit, you will learn to apply it in other areas of your life.

First Principle in Business<ref>First Principle and Business Development

The first thing you need to realize when trying to improve something from a first principle perspective, is that change is hard. Compare it to getting out of bed at 3.00 AM. It is not impossible to do it once or twice, but hard when it is more frequent.

Companies experience a similar issue with change. The mantra when things are going well can be summarized in “if it ain’t broke, don’t fix it”. Companies that experience that, get quickly rusted into habits, making change an unpopular priority. Even when change seems, in both foresight and hindsight, necessary.

Proof of that is the many retail shops that have closed in neighborhoods because they failed to embrace e-commerce on time.

The second thing you need to understand is that first principle follows a similar process as critical thinking or scientific reasoning. It follows the process of questioning, reflecting and coming with fundamental assumptions.

For the next part, the Socratic questioning has been adapted to create a model you can use (see figure below). It should guide you to apply first principle thinking in business scenarios you deem necessary.

The model compromises of five parts:

- Finding problem: As with anything related to business, you need to first identify a problem. Problems can be something encountered organically in a company, but it can also not be as clear or pressing. For example, figuring out how to become less dependable of a client or secure continuity are problems that can be deep and require reflection. However, both may not be urgent nor important depending on the risk threshold a company adopts. Questions that you can ask during this phase, should be about identifying the problem. Though, it may seem that finding the problem is enough, you should also investigate the feasibility of the solution. This will save time when it comes to the reiterative process, which can quickly become cumbersome when an irresolvable problem arises at a later stage. You can refer this stage also as the what stage. You do not necessarily have to adhere only to what questions, but it functions as a rule of thumb. Some example questions you can ask and reflect on are the following:

- What problems are urgent?

- What problems are important?

- What problems are both urgent and important?

- What other problems are both urgent and important?

- How can you verify or disprove whether it is a problem?

- What problems affect the company now?

- What problems will affect the company in the future?

- What are our competitors doing that may cause a problem in the future?

- What problems affect customers?

- What problems will affect our clients in the future?

- What problems affect staff?

- What problems will affect staff in the future?

- What problems affect other stakeholders?

- What other problems are similar in nature?

- How do we know that the problem is a problem?

- Why do we think solving the problem is worth the capital?

- Is the problem solvable?

- How is the problem solvable?

- Clarifying problem: Now that you have identified at least one problem, it is time to clarify the problem. Clarification will help in breaking down the problem to the most essential components. Moreover, it helps in structuring and framing the solutions at the end. When you clarify a problem, you will want to know exactly what the problem is and how it came to be. It is during this part that you also challenge the problem. If the problem happens to not be a problem, you need to go back to step one or grab the second problem you came across and forego the clarification process once more. Similar as before, you could define this stage as the how stage. Example questions could be:

- Why is it a problem?

- What do we know about the problem?

- What do we not know about the problem?

- What are the blind spots to the problem?

- How do we know about the blind spots?

- Why is solving the problem important?

- How can we look differently at the problem?

- How do the different divisions view the problem?

- How do customers view the problem?

- How do different stakeholders view the problem?

- What other explanations are there for the problem?

- What effect does the problem have on the business?

- Why does the problem affect the business?

- Why does the problem affect customers?

- What is true about the problem?

- How do we know that the problem is true?

- What is causing the problem?

- What are the counter arguments for the problem?

- Break down problem: Breaking the problem down allows you to look at the fundamental elements of the problem. Elements that if taken apart will give you a better idea of how to work things out. Think of it like a Lego construction. Taking pieces apart one by one, will yield building blocks (fundamental elements) that allows you to build something new. However, before doing so, you will need to make sure to create a blueprint of the current construction (continuing with the Lego example). Take the construction apart. Look at all the elements. Once you have done that you can go to the next stage to see whether you can improve the blueprint, create a complete new-one, demolish it and so on. During this stage a reward assessment is important. The way you could assess that is by asking three different questions. What happens if you do something, if you do not and if you ignore it. Needless to say, if nothing happens with all three scenarios you will need to go back to a different problem and reiterate.

As with the two previous stages, this is referred to as the why stage. Like before, this is not necessary to frame the question, but a why question digs deeper and breaks down the problem to the point where we cannot explain things further. Questions that can help you through are below, remember to ask why after each question:

- What is the essential part of the problem?

- What do we believe is the smallest part of the problem?

- How do we know what the smallest part of the problem is?

- What other components are there to the problem?

- Where does the problem originate?

- What is the blue-print of the problem?

- How can we test the problem?

- Which divisions are hindered by the problem?

- What conflict of interest is there with the problem?

- What ways does solving the problem help the business?

- What are the implications?

- What are the consequences?

- What happens if we do not act on the problem?

- What happens if we ignore the problem?

- happens if we do act on the problem?

- Solve problem: Now that you know what the problem is, how it affects the company, why the problem even exists and what part is exactly responsible for it, it is time to solve the problem. Continuing the analogy of before, with Lego. By taking apart the building blocks, you can use them to build something new. It may sound cryptic, but once you break things apart and look at the individual components, you should have the necessary information to solve the problem. During this phase it is important to come-up with different solutions and pit them against each other. Moreover, the solutions should be put into contrast with what the company can do and deliver. Lastly, it should be clear who is responsible for solving the problem and when the results should be seen. Some helpful questions would include:

- How can we solve the problem?

- What other solutions are there to the problem?

- Why is one solution better than the other?

- How does solving the problem affect the business?

- How does the solution benefit the business?

- What is the most important part to solve the problem?

- How do we know that the solution solves the problem?

- What do we have to solve the problem?

- What do we need to solve the problem?

- How does solving the problem affect the finances of the company?

- How is the investment worth solving the problem?

- What do we need to invest to solve the problem?

- What other problems does the solution solve?

- What other problems does the solution create?

- How does the solution affect all stakeholders?

- What happens if we cannot solve the problem?

- What can we learn after solving the problem?

- What knowledge and insights can we use to solve other problems?

- What steps are necessary to solve the problem?

- Who will be responsible for leading the solution to the problem?

- Who will monitor and evaluate?

- How do we measure solving the problem?

- Which solution is the team going to pursue?

- When is the solution going to be implemented?

- Question the questions: The last part is reviewing the total process you have gone through. You can question any of the previous phases and see if you have covered things that has not occurred before. During this stage, it is important to question the process, problem, clarification, break down and solution. If improvements need to be made, reiterate. If everything seems water proof, you can conclude and execute.

Despite how rational it sounds to think from first principle, it is not always the best way to go about problems. Companies are generally entities that are already efficient. Some companies or departments will undoubtedly be more efficient than others, but there are always tradeoffs when approaching things from first principle. Moreover, using first principle does not always yield positive or efficient results. Questioning everything (why) can sometimes result in unsatisfactory answers, wherein a company can conclude there is not much they can do about a problem. Furthermore, if that type of thinking is incorporated in a company without consequences, it can lead to a company that experiences the dreadful analysis paralysis.

- ↑ Definition - What does First Principles Thinking mean? Farnam Street

- ↑ First Principles frameworks Ayk Martirosyan