Accountable Care Organization (ACO)

Accountable care organization (ACO) is an umbrella term for a major switch in contracting between providers and public or private payers. In an ACO model, a group of providers, operating as a legal entity, contracts to assume some portion of the risk for cost and quality for a panel of beneficiaries through a variety of value-based payment models over a specified period of time. ACOs include primary care services. The U.S. CMS Distributed Shared Savings Program, which began operation in 2012, is one version of this model.[1]

The Origin of Accountable Care Organizations (ACO)[2]

{br}The term Accountable Care Organization was first coined in 2006 by Elliott Fisher, MD, Director of the Center for Health Policy Research at the Dartmouth Medical School. The ACO concept immediately sparked a great deal of interest and debate. Interest gained additional momentum in 2009 when the Affordable Care Act (ACA) used a specific CMS-drafted definition of an ACO. The following discussion focuses on the general ACO concept as defined by Fisher and others rather than the specific ACA definition. The ACO concept is one that is still evolving, but it can be generically defined as a group of health care providers, potentially including doctors, hospitals, health plans and other health care constituents, who voluntarily come together to provide coordinated high-quality care to populations of patients. The goal of coordinated care provided by an ACO is to ensure that patients and populations — especially the chronically ill — get the right care, at the right time and without harm, while avoiding care that has no proven benefit or represents an unnecessary duplication of services.

Accountable Care Organization (ACO) Principles[3]

There are three defined core ACO principles:

- Provider-led organizations with a strong base of primary care that are collectively accountable for quality and per capita costs across the continuum of care

- Payments linked to quality improvements and reduced costs

- Reliable and increasingly sophisticated performance measurement, to support improvement and provide confidence that savings are achieved through care improvements.

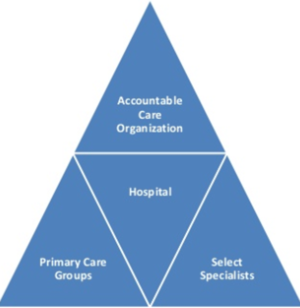

ACO Traditional Model Illustration

source: Healthcare Medical Pharmaceutical Directory

Types of Accountable Care Organization (ACO)[4]

ACOs can take different forms to meet local market conditions and existing levels of competition among providers. ACO programs have been piloted through the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) and the Center for Medicare & Medicaid Innovation (CMMI), as well by private payers.

- ACOs within CMS, such as the Medicare Shared Savings Program (MSSP), must sign a contract for three years. The minimum number of beneficiaries depends on the selected CMS ACO model.

- Commercial ACOs, like their Medicare counterparts, may receive reimbursement on shared savings for a defined population over a period of time. To achieve shared savings, certain quality and performance metrics must be met. Specific contract length and risk level vary from payer to payer. The goals of a commercial ACO mirror the goals of the CMS ACOs.

ACO Operating Model Illustration

source: ACO Watch

Pros, Cons and Challenges of Accountable Care Organization (ACO)[5]

It seems simple enough on the surface. By providing care within a specified network, losses and inefficiencies will be lowered. Also, since there is a specific focus on chronic disease, patients should receive better care. Breaking down the benefits on a granular level, they should be multi-faceted:

- Better care for patients, especially those with chronic disease.

- Less waste in the Medicare system.

- Physician-driven treatment.

- Financial incentives for successful ACOs.

But in order to tell the whole story we also have to discuss the potential cons of the system. This is where things get a bit tricky.

- Consolidation: It can be argued that this is a benefit, leading to better cross-network scheduling and lower patient cancellations. However there is also some concern being raised toward potentially monopolistic practices. Since an ACO must cover 5,000 Medicare patients in order to receive its benefits, in some areas a specific ACO will be the only choice for a patient, and therefore could raise its prices considerably. That said, the focus on quality of care should help to keep the rising costs in a system of checks and balances. And in many areas, monopolies already exist outside of the ACO format simply because consolidation has proven to be such a successful trend in the industry.

- Financial Benefits: For providers, operating successfully within the ACO can lead to financial rewards. For patients, lowered overall billing and lack of duplication of services should allow them to see less money spent to get quality care. That said, these benefits are being called into question because of the associated costs to set up an ACO. At best, according to some with knowledge of the matter, the benefits turn out to be a wash. At worst, they don’t begin to cover the new expenses or allow for efficient patient care.

- Rising Requirements: The early days of an ACO are the good days, according to some naysayers. The “low-hanging fruit” that can easily be trimmed can allow an ACO to meet the first tiers of requirements. However, as time goes on, the requirements are reassessed and the concern is that the increases will become insurmountable at some point in the not-so-distant future.

- Capitation: If you’re not familiar with the term, capitation is a system whereby a provider will be paid only a certain amount for the care of a single patient over a chosen period of time. While a patient needing less care could prove to be a financial boon to the provider, chronic disease patients (again, the focus of much of the ACO movement) are historically high-cost patients to treat. By placing a ceiling on the payments that can be provided, a patient risks seeing lessened care and the provider risks financial ruin.

- Difficult Implementation: The design of ACOs is based around sharing of information. For organizations that are already using some sort of EMR this task could be easier, but for those who have not then the financial and resource costs could prove to be more than a practice is willing to incur. It was initially thought that physician-led ACOs would be at a disadvantage because of their smaller size versus hospital-led ACOs. However, growth of ACOs over the first few years of their existence has shown that physician-driven groups have shown greater expansion, perhaps due to the hesitance of hospital-led groups to move away from a fee-for-service model. That said, studies are showing that older physicians are increasingly choosing retirement over changing away from how they have practiced medicine in the past, perhaps leading to a lack of necessary physicians in the future.

References

Further Reading

- ACOs make progress in using big data to improve care Modern Healthcare

- The Role of Healthcare Informatics in Accountable Care Inter Systems

- 5 Reasons Master Data Management (MDM) is Critical to The Success of a Data Driven Health System & Accountable Care Organization (ACO) VisionWare