Information Resource Management (IRM)

Business Dictionary defines Information Resource Management (IRM) as "techniques of managing information as a shared organizational resource." IRM includes

(1) identification of information sources,

(2) type and value of information they provide, and

(3) ways of classification, valuation, processing, and storage of that information.[1]

Information Resource Management (IRM) is a broad term in IT that refers to the management of records or information or data sets as a resource. This can relate to either business or government goals and objectives. Information resource management involves identifying data as an asset, categorizing it and providing various types of active management. Experts describe IRM as the process of managing the life cycle of data sets, from their creation to their use in IT architectures, and on to archiving and eventual destruction of non-permanent data. The term IRM can refer to either software resources, physical supplies and materials, or personnel involved in managing information at any stage of use.[2]

IRM provides an integrated view for managing the entire life-cycle of information, from generation, to dissemination, to archiving and/or destruction, for maximising the overall usefulness of information, and improving service delivery and program management. IRM views information and Information Technology as an integrating factor in the organisation, that is, the various organisational positions that manage information are coordinated and work together toward common ends. Further, IRM looks for ways in which the management of information and the management of Information Technology are interrelated, and fosters that interrelationship and organisational integration. IRM includes the management of

(1) the broad range of information resources, e.g., printed materials, electronic information, and microforms,

(2) the various technologies and equipment that manipulate these resources, and

(3) the people who generate, organise, and disseminate those resources. Overall the intent of IRM is to increase the usefulness of government information both to the government and to the public.[3]

According to Bergeron (1996), IRM is grounded in the following assumptions:

- recognition of information as a resource;

- an integrative management perspective;

- management of the information life cycle;

- a link with strategic planning (Schlögl, 2005).

One important feature of information resources management consists is that it is a framework that seeks to integrate different information professionals and functions under one umbrella. However there are different points of view on which resources are to be managed (Schlögl, 2005).

In a wide sense, information resources management can be defined as the management of those resources (human and physical) that are concerned with

- the systems support (development, enhancement, maintenance) and

- the servicing (processing, transformation, distribution, storage, and retrieval) of information (Schneyman 1985 as cited in Schlögl, 2005).

Marchand and Horton (1986) distinguish between information resources and information assets. Information resources include

- information specialists;

- information technology;

- facilities like the library,

- the data processing department, and

- the information centre and

- external information brokers (Schlögl, 2005).

Information assets cover all the formal information holdings of

- an organization (data, documents, technical literature),

- know-how (rights on intellectual property, practical experience of staff), as well as

- knowledge about the environment (competitors; political, economic, and social environment) (Schlögl, 2005).

While the information assets concern information itself, the information resources are a means by which information can be gained. Lytle (1988) has a somewhat narrower view. He differentiates between data, hardware, software, information systems and services, as well as personnel (Schlögl, 2005).[4]

Figure 1. source: M. Bryce & Associates

History of Information Resource Management (IRM)[5]

A foundational component of public administration, Information Resource Management (IRM) can be understood as a philosophy of management that recognizes and calls for the creation, identification, capture and management of information resources as corporate assets to enable and support the development of policy and effective decision making. The roots of modern IRM have a very long history, and may logically be traced back to the College of Notaries and the nascent bureaucracies of the Italian city-states and Signorie beginning in the mid-14th century, the great state chancelleries which emerged in England and France during the 15th and 16th centuries through to the appointment of a new class of public records administrators and archivists, seminally in France in the period immediately following the Revolution of 1789 (Brown, 1997; Cox, 2000; Leroux et al., 2009; Moore, 2008). Essentially, as the administration of the state became more complex and more sophisticated over time through the late medieval and early modern periods, so too did the management of its documents and records. By the end of the 19th moving into the early 20th century, codifications of rules and procedures for records management emerged in a series of administrative manuals, ultimately leading to the rise of a new professional class of bureaucrats uniquely occupied with the administration of documents and records (Jenkinson, 1922; Muller et al., 1940; Schellenberg, 1956). Western democracies also recognized early on that the effective management of their documents and records was fundamental to effective public administration. By the early 1970s, the rapid production of information and the gradual introduction of the computer in organizations everywhere led to the emerging notion of an information age in which information processing was acknowledged as having become a fundamental component of many jobs in industrialized nations. The subsequent emergence of the digital age engaged serious studies and debates on the evolving concept of information (Caron, 2011, Floridi, 2010, Leleu-Merviel and al., 2008). As indicated by Leleu-Merviel and codified in the RSQ, chapter C-1.1, information can now be understood to comprise both what is communicated– i.e., “The information is delimited and structured (…) and is intelligible in the form of words, sounds or images” – and how it is communicated – i.e., “information inscribed on a medium constitutes a document.” These evolving historical contexts provided the basis for various disciplines to contribute to the development and understanding of IRM (Papy, 2008; Salaün, 2009). For instance, in the field of public administration, IRM or Information Management is conceptualized as the “planning, organization, development and control of the information and data in an organization and of the people, hardware, software and systems that produce the data and information” (Fox and Meyer, 1995). In essence, the emergence of IRM reflects the impacts and influences of the digital age and related socioeconomic transformations within public administration. Looking at the contemporary roles and responsibilities now associated with IRM within the context of public administration and government, the continuous creation, capture, management, and preservation of authentic and reliable documentation has become a fundamental component of 21st-century administrative accountability consonant with transparent governance, effective corporate stewardship and the efficient delivery of programs and services to citizens through public business enterprise (Caron, 2011; Caron 2010). Today, the production and preservation of the documents and records of the state and its public administration in open and accessible form – especially in relation to policy development, decision-making, and interactive relationships between citizens and the machinery of government – is increasingly central to the constitution and maintenance of a democratic consensus conceived under the rule of law. Two of the core-essential principles currently operating within this domain of public administration are that:

(1) information resources determined to have long-term value as public or civic goods will be permanently preserved in a documentary resource repository such as an archive or library; and

(2) information resources without any ongoing business or public utility will be systematically disposed of in an open and transparent manner.

Society now provides normative standards created and recognized at the international level to

facilitate and enable the integration and implementation of these core-essential principles within the operations of public administration.

The Goals of Information Resource Management (IRM)[6]

The goals of IRM in the Paperwork Reduction Act fall into seven major categories]:

1. Paperwork Reduction: overseeing agencies' information collection requests, issuing guidance on the exercise of controls, and proposing changes in legislation to remove impediments. This involved facilitating sharing in information collection, the development of a Federal Information Locator System, and establishment of central collection agencies. Finally, standards were to be set for records retention and disposal.

2. Data Processing and Telecommunications: establishing policies for effective acquisition and utilization of computer and telecommunications resources. These included promoting the use of information processing technology and enforcing standards.

3. Statistics: developing long-range plans for improved performance of Federal statistical activities and the development and coordination of Government-wide statistical policies.

4. Records Management: correcting the deficiencies in existing records management practices and coordinating them with other IRM functions. A related objective was the development of standards for record retention for all sectors.

5. Information Sharing and Disclosure: managing decisions relative to the threat to privacy and confidentiality. Policy guidance on disclosure of information, confidentiality, and security of information would be set. To enhance general management practice, it recommended legislation to remove the inconsistencies.

6. Information Policy and Oversight: establishing a strong, central management function responsible for the development of uniform and consistent information policies. To insure success, the agencies were to be given adequate guidance in the conduct of their information management activities.

7. Organization Development and Administration: creating the steps necessary for the establishment and funding of the Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs.

The goals in the private sector centered around the elimination of redundant document processing activities and facilitating access to the information. This view reflects an awareness of the variety of media available for information storage and presentation, and proposes greater integration of people, tools, and systems in order to improve the quality of the information product.

Information Resource Management (IRM) - How it's Done[7]

1. Understand the role of Information: Information can add value to your products and services. Improved information flows can improve the quality of decision making and internal operations. Yet many managers do not fully understand the real impact of information - the cost of a lost opportunity, of a poor product, of a strategic mistake - all risks that can be reduced by using the appropriate information.

2. Assign Responsibility for Leading your IRM Initiative: Developing value from information resources is often a responsibility that falls between the cracks of several departments - the user departments in different business units, and corporate planning, MIS units or librarians.

3. Develop Clear Policies on Information Resources: Policies for ascertaining information needs, acquiring and managing information throughout its life cycle. Pay particular attention to ownership, information integrity and sharing. Make the policies consistent with your organisational culture.

4. Conduct an Information Audit (Knowledge Inventory): Identify current knowledge and information resources (or entities), their users, usage and importance. Identify sources, cost and value. Classify information and knowledge by its key attributes. Develop knowledge maps. As knowledge management gains prominence, this is sometimes called a knowledge inventory "knowing what you know".

5. Link to Management Processes: Make sure that key decision and business process are supported with high leverage information. Assess each process for its information needs.

6. Systematic scanning: Systematically scan your business environment. This includes the wider environment - legal and regulatory, political, social, economic and technological - as well as the inner environment of your industry, markets, customers and competitors. Provide selective and tailored dissemination of vital signs to key executives. This goes beyond the daily abstracting service provided by many suppliers.

7. Mix hard/soft, internal/external: True patterns and insights emerge when internal and external data is juxtaposed, when hard data is evaluated against qualitative analysis. Tweak your MkIS system to do these comparisons.

8. Optimize your information purchases.You don't have to control purchasing, but most organisations do not know how much they are really spending on external information. By treating consultancy, market research, library expenses, report and databases as separate categories, many organisations are confusing media with content.

9. Introduce mining and refining processes: Good information management involves 'data mining', 'information refining' and 'knowledge editing'. You can use technology such as intelligent agents, to help, but ultimately subject matter experts are needed to repackage relevant material in a user friendly format. One useful technique is content analysis, whose methods have been developed by Trend Monitor International in their Information Refinery, and are used in our analysis services. The classifying, synthesising and refining of information combines the crafts of the information scientist, librarian, business analyst and market researcher/analyst. Yet many organisations do not integrate these disciplines.

10. Develop Appropriate Technological Systems: Continual advances in technology increase the opportunities available for competitive advantage through effective information management. In particular,intranets, groupware and other collaborative technologies make it possible for more widespread sharing and collaborative use of information. Advances in text retrieval, document management and a host of other trends in knowledge management technologies have all created new opportunities for providers and users alike.

11. Exploit technology convergence:Telecommunications, office systems, publishing, documentation are converging. Exploit this convergence through open networking, using facilities such as the World Wide Web, not just for external information dissemination but for sharing information internally.

12. Encourage a Sharing Culture: Information acquires value when turned into intelligence. Market Intelligence Systems (MkIS) are human expert-centred. Raw information needs interpretation, discussing and analysing teams of experts, offering different perspectives. This know- how sharing is a hall-mark of successful organisations

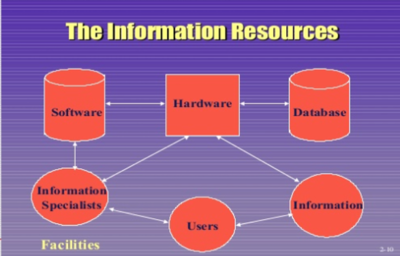

Components of Information Resource Management (IRM) (Figure 2.)[8]

Below is a diagrammatic illustration of the information resources that form the essential components of Information Resource Management (IRM) in a modern organization:

Figure 2. source: Dhani Ahmad

Effective IRM Management[9]

Nick Willard of ASLIB's IRM Network (now the IRM SIG) has developed a model highlighting the five key activities for their effective IRM management:

- Identification What information is there? How is it identified and coded?

- Ownership Who is responsible for different information entities and co-ordination?

- Cost and Value A basic model for making judgements on purchase and use

- Development Increasing its value (see '10 ways to add value to your business') or stimulating demand.

- Exploitation Proactive maximization of value for money

Implementing Information Resource Management (IRM)[10]

- Implementing Information Resource Management (IRM) requires a long term strategy. In implementing IRM strategy senior managers must not be concerned simply with quick results to information problems or technical fixes to their operational problems. IRM requires a long term view of organizational change and adjustment.

- Information Resource Management (IRM) must be implemented incrementally and not all at once. IRM requires attention to many areas of responsibility. In implementing IRM it is unlikely that an organization will seek to address and resolve issues in all areas at one time. Instead, the IRM plan should provide a path by which the areas of greatest concern are addressed in a phased manner.

- Implementing Information Resource Management (IRM) requires only attention to and planning for administrative changes that may be needed. Inevitably, even in phase 1 the IRM strategy will require attention to realigning organizational subunits or reassigning management and technical staff, In other cases, IRM may require changes in procurement policies for IT or interpretations of rules and procedures. In still other instances, IRM may require that the organization create new positions, such as an IRM Director or IR planner. In all these cases, the successful implementation of IRM plans will need to anticipate such policy, regulatory, and administrative changes.

- Implementation of IRM requires consistency in executive leadership. A major ingredient for successful IRM implementation is consistency and stability in the organization's executive leadership. Since the implementation of IRM can require from three to five years, and therefore necessitate a strong consensus on the part of the senior managers of the organization that IRM is worth pursuing, frequent changes in this leadership group will lead to inconsistency in the pursuit of IRM objectives and plans.

Barriers to IRM[11]

Ineffective information resource management often results in massive cost overruns, long schedule delays, and systems that do not perform as intended. Some of the causes to this ineffectiveness are:

- a. Lack of well-defined IRM concepts

- b. Lack of IRM training or awareness

- c. Lack of agreement on objectives

- d. Lack of ability to attract and retain skilled people

Benefits of Information Resource Management (IRM)[12]

IRM has Numerous Benefits

- IRM assists in development of systems that are targeted to support strategic and operational objectives;

- In IRM , there is increased integration of technologies, which improves the sharing of information across the organization and makes it easier to obtain information for changing decision-making needs;

- IRM Assist in identification and adoption of appropriate information technology standards, minimizing dependence on specific suppliers of hardware or software;

- IRM helps in identification of opportunities to improve the relevance and adequacy of information provided and activities performed;

- IRM offers a technological infrastructure that will support the strategic business plan;

- IRM helps in minimization of duplicate, and possibly inconsistent, data and processing capabilities within the organization's portfolio of information systems;

- There is prioritization of projects to be implemented and greater cost-justification of system development and maintenance activities.

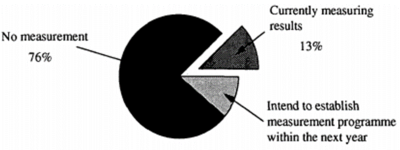

The Importance of Measuring IRM Benefits (Figure 3.)[13]

While there is considerable literature on IRM techniques and their potential benefits (eg McKenney and McFarlan, 1982; Martin, 1989; Katz, 1990; Kerr, 1991; Hancock, 1992; Hufford, 1993; English, 1993; Love, 1993), there has been little serious attempt at quantification of these benefits. There are few published cases in the literature of successful IRM efforts, and very few, if any, with benefits quantified in dollar terms. "Success stories" which are regularly presented at industry forums such as IBM's Share-Guide (eg Hancock, 1992) or the Data Administration and management Association (DAMA), seldom report quantitative benefits, and usually represent the only the perspective of the IRM group, which has a vested interest in being perceived as effective.

A recent survey of IRM practitioners in the U.S. (Figure 3) showed that only 13% of organisations had implemented procedures for measuring IRM performance (English and Green, 1991). In the absence of any formal measurement of the impact of IRM in practice, the assumption that IRM adds value to the business remains essentially an unproven one. As Strassman (1985) says, "you cannot tell whether you have improved something if you have not measured its performance". Aside from purely anecdotal evidence, there is little to say whether IRM has had a net positive or negative effect in organisations. Measurement provides a means for particular functions within an organisation to quantify and improve their value to the organisation. Effective measures serve as a framework for defining shared goals and for communicating how the goals of each function support organisational goals (Walrad and Moss, 1993). Measurement of IRM effectiveness is important both from the perspective of individual organisations, who need to assess the return on their investment in IRM, and from the broader perspective of establishing sound industry practices.

Figure 3. source: Daniel L. Moody & Graeme C. Simsion

- Justifying Initial Investment in IRM: In the past, it may have been sufficient to demonstrate the apparent logic of properly managing information, or to cite the results of past mis-management, in order to convince an organisation to invest in IRM. There is a major emphasis both in the literature and in practice on "selling" the benefits of IRM. As one IRM manager said, "... the marketing of IRM is a continual necessity, particularly in the light of the difficulty in quantifying its benefits." (Green, 1989b). Such approaches are becoming less effective in the absence of well-documented success stories, and the requirement for sound quantified business cases to support all IT investment. A study of 31 organisations implementing IRM carried out by Goodhue et al (1988) showed that the successful companies in the sample justified IRM not by conceptual or technical arguments but by compelling business needs.

- Survival of the IRM Group: In today's economic climate, organisations are looking to maximise return on investment in all areas of the business, and to cut back in areas that are not directly contributing to profitability. Usually "infrastructure" groups, such as IRM, are the first victims of cost cutting exercises (Simsion and Drummond, 1990). Because they do not contribute directly to the task of delivering systems, they are seen as expendable in times of crisis. The existence of formal measurement of results acts as an effective insurance policy against such a demise.

- Management Support: Lack of management support is consistently cited by IRM practitioners as the major reason why IRM does not succeed and as the major obstacle to achieving ongoing success (English and Green, 1991; Martin, 1989). The exercise is more likely to fail from a lack of management commitment than from any technical reasons. Perhaps management are right in withdrawing support for a group which cannot justify its value to the organisation. Management will not continue to support a concept that cannot demonstrate measurable benefits to the firm.

- Clarifying Goals: IRM groups are often established with a rather vague charter, for example "to manage data as a corporate asset", or "to promote integration and sharing of data throughout the organisation". However it is very difficult to translate slogans into action. As a result, in spite of large amounts of effort and good intentions, they end up achieving very little. Without clearly defined goals and ways of measuring progress against these goals, IRM groups often lack direction and focus. Just the process of defining goals and measures will help IRM groups to define what their charter really means, and clarify the role and function of IRM in the organisation.

- Focussing IRM Investment: Measurement of results is fundamental to ensuring that activities are concentrated in areas of most benefit (Darcy, 1994). An IRM group may take a variety of initiatives all aimed at improving the management of information: eg establishing standards for data formats, reviewing database designs prior to implementation, implementing a repository. It is important to be able to measure the effect of each initiative in order to focus resources where they are providing greatest benefit, and to identify problem areas. For example, effort expended on integration should be proportional to the need for integration: in some areas, overheads may be higher than the benefits (Goodhue et al, 1988, 1992).

- Ensuring Conformance: One of the major obstacles to the success of IRM in practice is ensuring that development projects conform to the enterprise data model. By itself, an enterprise data model is nothing more than an idealised picture of how an organisation's data should be structured. It becomes valuable only if it is used in practice. Many enterprise data models are ignored after they are completed and the expense put into developing them is wasted (Butler Cox, 1988; IBM, 1992). This is despite conformity to the model being mandated by standards in many

See Also

Information Technology (I.T.)

Information Technology (IT) Transformation

Enterprise Architecture

Enterprise Architecture Framework

Design & Engineering Methodology for Organizations (DEMO)

Information Management (IM)

Strategic Vision

Enterprise Information Integration (EII)

Enterprise Information Management (EIM)

Enterprise Information Security Architecture (EISA)

Information System (IS)

Resource Management

References

- ↑ Definition of Information Resource Management (IRM) Business Dictionary

- ↑ Explaining Information Resource Management (IRM) Techopedia

- ↑ What is Information Resource Management (IRM)? The Free Dictionary

- ↑ Understanding Information Resource Management (IRM)? Tallinna Ülikool

- ↑ History of Information Resource Management (IRM) EDPA

- ↑ What are the Goals of Information Resource Management (IRM) Eileen M. Trauth

- ↑ How is IRM Done? Komal Gupta

- ↑ What are the Components of IRM in a Modern Organization Dhani Ahmad

- ↑ Five key activities for their effective IRM management David Skyrme Assoc.

- ↑ Implementing Information Resource Management (IRM) successfully Jack Rabin

- ↑ Barriers to IRM Komal Gupta

- ↑ What are the Benefits of Information Resource Management (IRM) CivilServiceIndia

- ↑ What is the Importance of Measuring IRM Benefits Daniel L. Moody & Graeme C. Simsion

Further Reading

- An Empirical Assessment of the Information Resource Management Construct Bruce R. Lewis, Charles A Snyder, R Kelly Rainer, Jr.

- Information Resources Management Strategic Plan 2014-2018 Department of Energy USA

- Elevating the Role of Information Resource Management for Business Efectiveness IMAC, Larry P. English

- The Evolution of Information Resource Management Eileen M. Trauth

- Justifying the Investment in Information Resource Management Daniel L. Moody & Graeme C. Simsion

- Information Resource Management in a Knowledge Society V. Rajendran and E. Soundararajan