Product Life Cycle

Definition of Product Life Cycle

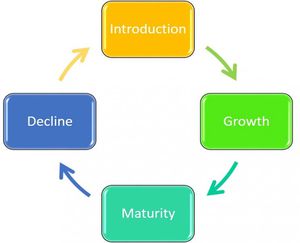

Product Life Cycle (PLC) is the progression of an item through the four stages of its time on the market. The four life cycle stages are: Introduction, Growth, Maturity and Decline. Every product has a life cycle and time spent at each stage differs from product to product.[1]

Product life cycle (PLC) is the cycle through which every product goes through from introduction to withdrawal or eventual demise. PLC analysis, if done properly, can alert a company as to the health of the product in relation to the market it serves. PLC also forces a continuous scan of the market and allows the company to take corrective action faster. But the process is rarely easy.[2]

How Product Life Cycles Work[3]

A product begins with an idea, and within the confines of modern business, it isn't likely to go further until it undergoes research and development and is found to be feasible and potentially profitable. At that point, the product is produced, marketed, and rolled out. The product introduction phase generally includes a substantial investment in advertising and a marketing campaign focused on making consumers aware of the product and its benefits. Assuming the product is successful, it enters its growth phase. Demand grows, production is increased, and its availability expands. As a product matures, it enters its most profitable stage, while the costs of producing and marketing decline. However, it inevitably begins to take on increased competition as other companies emulate its success, sometimes with enhancements or lower prices. The product may lose market share and begin its decline. The stage of a product's life cycle impacts the way in which it is marketed to consumers. A new product needs to be explained, while a mature product needs to be differentiated from its competitors.

New Product Development Stages[4]

Before a product can embark on its journey through the four product life cycle stages, it has to be developed. New product development is typically a huge part of any manufacturing process. Most organizations realize that all products have a limited lifespan, and so new products need to be developed to replace them and keep the company in business. Just as the product life cycle has various stages, new product development is also broken down into a number of specific phases. Developing a new product involves a number of stages which typically center around the following key areas:

source: http://productlifecyclestages.com

- The Idea: Every product has to start with an idea. In some cases, this might be fairly simple, basing the new product on something similar that already exists. In other cases, it may be something revolutionary and unique, which may mean the idea generation part of the process is much more involved. In fact, many of the leading manufacturers will have whole departments that focus solely on the task of coming up with ‘the next big thing’.

- Research: An organization may have plenty of ideas for a new product, but once it has selected the best of them, the next step is to start researching the market. This enables them to see if there’s likely to be a demand for this type of product, and also what specific features need to be developed in order to best meet the needs of this potential market.

- Development: The next stage is the development of the product. Prototypes may be modified through various design and manufacturing stages in order to come up with a finished product that consumers will want to buy.

- Testing: Before most products are launched and the manufacturer spends a large amount of money on production and promotion, most companies will test their new product with a small group of actual consumers. This helps to make sure that they have a viable product that will be profitable, and that there are no changes that need to be made before it’s launched.

- Analysis: Looking at the feedback from consumer testing enables the manufacturer to make any necessary changes to the product, and also decide how they are going to launch it to the market. With information from real consumers, they will be able to make a number of strategic decisions that will be crucial to the product’s success, including what price to sell at and how the product will be marketed.

- Introduction: Finally, when a product has made it all the way through the new product development stage, the only thing left to do is introduce it to the market. Once this is done, good product life cycle management will ensure the manufacturer makes the most of all their effort and investment.

Thousands of new products go on sale every year, and manufacturers invest a lot of time, effort and money in trying to make sure that any new products they launch will be a success. Creating a profitable product isn’t just about getting each of the stages of new product development right, it’s also about managing the product once it’s been launched and then throughout its lifetime. This product life cycle management process involves a range of different marketing and production strategies, all geared towards making sure the product life cycle curve is as long and profitable as possible.

Product Life Cycle (PLC) Stages[5]

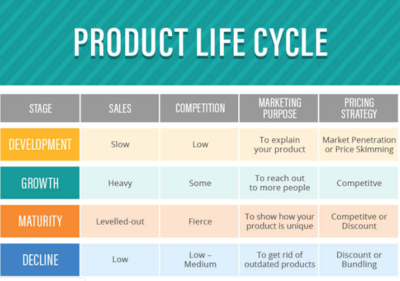

A new product progresses through a sequence of stages from introduction to growth, maturity, and decline. This sequence is known as the product life cycle and is associated with changes in the marketing situation, thus impacting the marketing strategy and the marketing mix. The product revenue and profits can be plotted as a function of the life-cycle stages as shown in the graph below:

- Introduction Stage: In the introduction stage, the firm seeks to build product awareness and develop a market for the product. The impact on the marketing mix is as follows:

- Product branding and quality level is established, and intellectual property protection such as patents and trademarks are obtained.

- Pricing may be low penetration pricing to build market share rapidly, or high skim pricing to recover development costs.

- Distribution is selective until consumers show acceptance of the product.

- Promotion is aimed at innovators and early adopters. Marketing communications seeks to build product awareness and to educate potential consumers about the product.

- Growth Stage: In the growth stage, the firm seeks to build brand preference and increase market share.

- Product quality is maintained and additional features and support services may be added.

- Pricing is maintained as the firm enjoys increasing demand with little competition.

- Distribution channels are added as demand increases and customers accept the product.

- Promotion is aimed at a broader audience.

- Maturity Stage: At maturity, the strong growth in sales diminishes. Competition may appear with similar products. The primary objective at this point is to defend market share while maximizing profit.

- Product features may be enhanced to differentiate the product from that of competitors.

- Pricing may be lower because of the new competition.

- Distribution becomes more intensive and incentives may be offered to encourage preference over competing products.

- Promotion emphasizes product differentiation.

- Decline Stage: As sales decline, the firm has several options:

- Maintain the product, possibly rejuvenating it by adding new features and finding new uses.

- Harvest the product - reduce costs and continue to offer it, possibly to a loyal niche segment.

- Discontinue the product, liquidating remaining inventory or selling it to another firm that is willing to continue the product.

The marketing mix decisions in the decline phase will depend on the selected strategy. For example, the product may be changed if it is being rejuvenated, or left unchanged if it is being harvested or liquidated. The price may be maintained if the product is harvested, or reduced drastically if liquidated.

Preparing for the Product Life Cycle[6]

There is no definite way you can prepare for the product life cycle. You can’t predict the exact amount of time the product will be in each stage. But, understanding the product life cycle will help you know how to handle pricing strategies, competition, and marketing.

source: Patriot Software

Product Life Cycle Management[7]

To effectively manage the product life cycle, organisations need to have a very strong focus on a number of key business areas:

- Development: Before a product can begin its life cycle, it needs to be developed. Research and new product development is one of the first and possibly most important phases of the manufacturing process that companies will need to spend time and money on, in order to make sure that the product is a success.

- Financing: Manufacturers will usually need significant funds in order to launch a new product and sustain it through the Introduction stage, but further investment through the Growth and Maturity stages may be financed by the profits from sales. In the Decline Stage, additional investment may be needed to adapt the manufacturing process or move into new markets. Throughout the life cycle of a product, companies need to consider the most appropriate way to finance their costs in order to maximize profit potential.

- Marketing: During a product’s life, companies will need to adapt their marketing and promotional activity depending on which stage of the cycle the product is passing through. As the market develops and matures, the consumers attitude to the product will change. So the marketing and promotional activity that launches a new product in the Introduction Stage, will need to be very different from the campaigns that will be designed to protect market share during the Maturity Stage.

- Manufacturing: The cost of manufacturing a product can change during its life cycle. To begin with, new processes and equipment mean costs are high, especially with a low sales volume. As the market develops and production increases, costs will start to fall; and when more efficient and cheaper methods of production are found, these costs can fall even further. As well as focusing on marketing to make more sales and profit, companies also need to look at ways of reducing cost throughout the manufacturing process.

- Information: Whether it’s data about the potential market that will make a new product viable, feedback about different marketing campaigns to see which are most effective, or monitoring the growth and eventual decline of the market in order to decide on the most appropriate response, information is crucial to the success of any product. Manufacturers that efficiently manage their products along the product life cycle curve are usually those that have developed the most effective information systems.

Most manufacturers accept their products will have a limited life. While there may not be much they can do to change that, by focusing on the key business areas mentioned, product life cycle management allows them to make sure that a product will be as successful as possible during its life cycle stages, however long that might be.

Linear PLC and Circular PLC[8]

So far, we have been discussing the typical PLC. It is linear and at each stage has material, labor, and resource inputs. It also has waste outputs that can negatively affect the environment. Researchers assert that the introduction stage where design takes place determines between 70 percent and 90 percent of the life cycle costs. At this stage, manufacturers can also remove excess waste and continue to develop sustainable manufacturing practices. These practices should include products being reused, recycled, and remanufactured. With this, you are developing a closed-loop manufacturing cycle. Instead of a linear PLC, this represents a circular PLC.

A closed-loop cycle is a natural extension of PLM, and creates a truly full life cycle that takes your obsolete or used products back into raw materials, not just assigning them to waste. Although many of these closed-loop products are down cycled (converted into lesser-quality materials), the products are still recycled and reused repeatedly.

An example of this is Dell’s take-back program, which takes the computers that it manufacturers and turns a majority of them into new computers. Other companies separate out product components and sell them to their partners on the commodities market, as raw materials, who then make them into new products. The benefits of a closed-loop system include:

- Better for the environment

- Does not affect performance or price

- Fewer carbon emissions in manufacturing

- As programs scale, they become cheaper and more effective

Product Life Cycle of A Mobile App[9]

The traditional PLC theory has been developed in the pre-internet world dominated by tangible products and offline services. Therefore, the application of PLC in the digital world requires certain modification. First of all, internet provides a vast amount of information to users and word-of-mouth travels much faster. Therefore, information in the form of user reviews became highly important determinant in software adaptation (Duan, et al., 2009). In the context of apps, both apps ranking (within its depository) and user reviews affect its adoption (Carare, 2012). Obviously, user sometimes do not have time to address all the competing alternatives (e.g. apps offering same service) and they would end up following others (Duan, et al., 2009). Through online reviews, online users are informed about other users’ choice and the overall ranking of particular app, which makes their decisions easier. Furthermore, in the context of paid apps, a research study also revealed that users are prepared to pay more for a top ranked app than say unranked app (Carare, 2012). Besides the online information overload, the app market is constantly growing offering millions of apps. Since users are sometimes reducing their post-purchase dissonance by following other peoples’ behaviour or by following a herd, a vast number of apps will end-up below the radar. On the other hand, popular apps will become even more popular making their growth curve even steeper. This herding phenomenon had been observed in many different fields, such as financial markets (Bikhchandani & Sharma, 2001) or TV broadcasting (Kennedy, 2002). The phenomenon has also been recognised among the web users (Simonsohn & Ariely, 2008), so herding in the context of apps can be considered as a spill-over effect in the app market context.

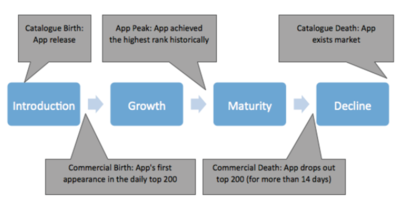

App’s PLC within the context of daily download rank

source: IJMC (adopted from Liu, et al., 2014, p. 2).

Liu et al. (Liu, et al., 2014) suggested the following distinctive stages in the lifecycle of an app (see Figure below):

- App catalogue birth – product is released and available for download in the app depository (e.g. Apple’s Store or Google Play);

- App commercial birth – begins when the app starts to gain a relatively large number of downloads (e.g. an app's will appear in the daily top-200 download rank list once it gets a decent number of downloads);

- App peak – represents the app’s highest sales level (i.e. there are at least two peaks – its peak ranking relative to all apps, and its categorical peak);

- App commercial death – occurs when the app’s downloads fall below certain threshold (e.g. out of the top-200 for more than 14 consecutive days);

- Catalogue death – refers to the removal of the product from its developer's catalogue.

Taking into consideration the herding phenomenon within the app market context, if an app succeeds reaching a decent number of daily downloads, it will appear on the top list, which will result with even more downloads. On the other hand, if an app does not reach the top list, it will skip the growth stage. Empirical evidence points to the value of the large user base that can be tapped into either to extend maturity or escape decline phase of the product life cycle. Having a large number of users of a game provides the game developer with an opportunity to increase the value of the game for each user by expanding the functionality of the game through adding multiplayer features. This essentially creates value for users through network effects as has been observed in many technology related industries (Marchand, 2016). Large user base tends to provide valuable source of additional revenues when growth rate of new users declines or stops. Hence, it becomes of high importance to maximize the user base in the growth phase of the product life cycle curve. However, user base growth has to be carefully balanced with revenue generation. Usually, there is a tradebetween the two. If game developer starts appropriating value from the users too soon (through different revenue models) this might hamper the growth rate, however, if the monetization starts too late, the bottom line will be hurt. This points to the paramount importance of choosing the right business model for the game that will drive the growth of the app and allow for later date revenue generation with the aim of maximizing profits from the game (Nielsen & Lund, 2018).

Product Life Cycle in Respect to The Technology Life Cycle[10]

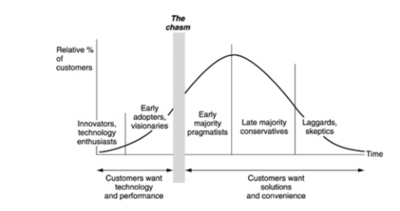

As a new technology matures so is the product or service that uses this technology. The change that occurs during a technology life cycle has a unique reflection on the customers and so on the product life cycle.

In the early days of a new technology, early adopters and technology enthusiasts drive a market since they demand just technology. This drive and demand is translated as the introduction phase of a new product by many companies. As technology grows old, customers become more conservative and demand quick solutions and convenience. In this case a product usually enters in the realm of its growth and as time passes its maturity.

Change in customers as technology matures

source: URENIO (Norman D.)

The “chasm” shown in the graph above depicts the difference between the early and late adopters. Each needs different marketing strategies and each is translated to a product’s different phase of its life cycle. One should note that the late adopters hold the greatest percentage of customers in a market. This is why most products begin their life cycle as technology driven and change into customer driven as time passes by. A good example of this is the computer market. In one hand customers ask for ease of use, convenience, short documentation and good design. On the other hand

customers rush out to purchase anything new regardless of its complexity. This is why companies in the computer industry withdraw their products long before they reach their maturity phase. This is the moment that a product reaches its peak i.e. the time that both early and late adopters buy the product.

Product Life Cycle Examples[11]

The traditional product life cycle curve is broken up into four key stages. Products first go through the Introduction stage, before passing into the Growth stage. Next comes Maturity until eventually the product will enter the Decline stage. These examples illustrate these stages for particular markets in more detail.

- 3D Televisions: 3D may have been around for a few decades, but only after considerable investment from broadcasters and technology companies are 3D TVs available for the home, providing a good example of a product that is in the Introduction Stage.

- Blue Ray Players: With advanced technology delivering the very best viewing experience, Blue Ray equipment is currently enjoying the steady increase in sales that’s typical of the Growth Stage.

- DVD Players: Introduced a number of years ago, manufacturers that make DVDs, and the equipment needed to play them, have established a strong market share. However, they still have to deal with the challenges from other technologies that are characteristic of the Maturity Stage.

- Video Recorders: While it is still possible to purchase VCRs this is a product that is definitely in the Decline Stage, as it’s become easier and cheaper for consumers to switch to the other, more modern formats.

Another example within the consumer electronics sector also shows the emergence and growth of new technologies, and what could be the beginning of the end for those that have been around for some time.

- Holographic Projection: Only recently introduced into the market, holographic projection technology allows consumers to turn any flat surface into a touchscreen interface. With a huge investment in research and development, and high prices that will only appeal to early adopters, this is another good example of the first stage of the cycle.

- Tablet PCs: There are a growing number of tablet PCs for consumers to choose from, as this product passes through the Growth stage of the cycle and more competitors start to come into a market that really developed after the launch of Apple’s iPad.

- Laptops: Laptop computers have been around for a number of years, but more advanced components, as well as diverse features that appeal to different segments of the market, will help to sustain this product as it passes through the Maturity stage.

- Typewriters: Typewriters, and even electronic word processors, have very limited functionality. With consumers demanding a lot more from the electronic equipment they buy, typewriters are a product that is passing through the final stage of the product life cycle.

While it’s usually left up to the manufacturers and their marketers to worry about Product Life Cycle Management and what implications the different stages might have for their business, considering actual products is a good way to show consumers the part they play in this life cycle.

Pyramid of Production Systems[12]

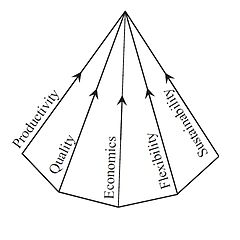

According to Malakooti (2013), there are five long-term objectives that should be considered in production systems:

- Cost: Which can be measured in terms of monetary units and usually consists of fixed and variable cost.

- Productivity: Which can be measured in terms of the number of products produced during a period of time.

- Quality: Which can be measured in terms of customer satisfaction levels for example.

- Flexibility: Which can be considered the ability of the system to produce a variety of products for example.

- Sustainability: Which can be measured in terms ecological soundness i.e. biological and environmental impacts of a production system.

The relation between these five objects can be presented as pyramid with its tip associated with the lowest Cost, highest Productivity, highest Quality, most Flexibility, and greatest Sustainability. The points inside of this pyramid are associated with different combinations of five criteria. The tip of the pyramid represents an ideal (but likely highly unfeasible) system whereas the base of the pyramid represents the worst system possible.

Pyramid of Production Systems

source: Wikipedia

Product Life Cycle - What You Need to Bear in Mind

As a model, the curve provides a good approximation of the sales and profits that can be expected as products pass through the four stages of the typical life cycle. However, there are a few things to bear in mind when trying to apply the Product Life Cycle Curve in the real world.

- Unpredictability: While a product’s life may be limited, it is very hard for manufacturers to predict exactly how long it is likely to be, especially during the new product development phase. While most manufacturers are very good at making the best decisions based on the information they have, consumer demand can be unpredictable, which means they don’t always get it right.

- Change: The unpredictability of a products life span comes from the fact that all the factors that influence the product life cycle are constantly changing. For example, changes in the cost of production or a fall in consumer demand due to the launch of alternative products, could significantly alter the duration of the different product life cycle stages.

- The Curve is a Model: Critics of the product life cycle have claimed that some manufacturers may place too much importance on the suggestions the model makes, so that it eventually becomes self-fulfilling. To illustrate the point, if a company uses the product life cycle curve as a basis for its decisions, a decrease in sales may lead them to believe their product is entering the Decline stage and therefore spend less on promoting it, when the opposite strategy could help them to capture more market share and actually increase sales again.

While the Product Life Cycle Curve needs to be applied with a certain amount of care, and manufacturers are unlikely to rely solely on it’s simple illustration to predict their sales and profits, it is still a useful tool. With a general appreciation of the kind of challenges that will be faced during each of the four stages, the model provides businesses and their marketing departments with the opportunity to be plan ahead and be better prepared to meet those challenges.

Criticisms of the PLC[13]

As we have seen, the PLC has the ability to offer marketers guidance on strategies and tactics as they manage products through changing market conditions. Unfortunately, the PLC does not offer a perfect model of markets as it contains drawbacks that prevent it from being applicable to all products. Among the problems cited are:

- Shape of Curve – Some product forms do not follow the traditional PLC curve. For instance, clothing may go through regular up and down cycles as styles are in fashion then out then in again. Fad products, such as certain toys, may be popular for a period of time only to see sales drop dramatically until a future generation renews interest in the toy.

- Length of Stages – The PLC offers little help in determining how long each stage will last. For example, some products can exist in the Maturity stage for decades while others may be there for only a few months. Consequently, it may be difficult to determine when adjustments to the Marketing Plan are needed to meet the needs of different PLC stages.

- Competitor Reaction is Not Predictable – As we saw, the PLC suggests that competitor response occurs in a somewhat consistent pattern. For example, the PLC says competitors will not engage in strong brand-to-brand competition until a product form has gained a foothold on the market. The logic is that until the market is established it is in the best interest of all competitors to focus on building interest in the product form itself and not on claiming one brand is better than another. However, competitors do not always conform to theoretical models. Some will always compete on brand first and leave it to others to build market interest for the product form. Arguments can also be made that competitors will respond differently than what the PLC suggests on such issues as pricing, number of product options, spending on declining products, to name a few.

- Patterns May Not Apply to All Global Markets – Marketers who base their strategies on how the PLC plays out in their home market may be surprised to see the PLC does not follow the same patterns when they enter other global markets. The reason is that customer behavior may be quite different within each market. For instance, a company may find that while customers in their home market easily understand how the company’s new product could save them time in performing a certain task, customers in a foreign market may not easily see the connection.

- Impact of External Forces – The PLC assumes customers’ decisions are primarily impacted by the marketing activities of the companies selling in the market. In fact, as we discussed in the Managing External Forces Tutorial, there are many other factors affecting a market, which are not controlled by marketers. Such factors (e.g., social changes, technological innovation) can lead to changes in market demand at rates that are much more rapid than would occur if only an organization’s marketing decisions were being changed (i.e., if everything was held constant except for company’s marketing decisions).

- Use for Forecasting – The impact of external forces may create challenges in using the PLC as a forecasting tool. For instance, market factors not directly associated with the marketing activities of market competitors, such as economic conditions, may have a greater impact on reducing demand than customers’ interest in the product. Consequently, what may be forecast as a decline in the market, signaling a move to the Maturity stage, may be the result of declining economic conditions and not a decline in customers’ interest in the product. In fact, it is likely demand for the product will recover to growth levels once economic conditions improve. If a marketer follows the strict guidance of the PLC he/she would conclude that strategies should shift to those of the Maturity stage. Doing so may be an overreaction that could hurt market position and profitability.

- Stages Not Seamlessly Connected – Some high-tech marketers question whether one stage of the PLC naturally will follow another stage. In particular, technology consultant Geoffrey Moore suggests that for high-tech products targeted to business customers, a noticeable space or “chasm” occurs between the Introduction and Growth stages that can only be overcome by significantly altering marketing strategy beyond what is suggested by the PLC.

Pros and Cons of the Product Life Cycle[14]

- Pros of the Product Life Cycle

- The product life cycle helps with planning. Marketing managers can check which stage they're currently in, in terms of the product life cycle and to make the appropriate changes to their marketing strategies.

- The product life cycle also helps managers avoid the pitfalls of the different stages. By comparing their products to similar products at similar stages in their life cycles, they can spot mistakes and trends before they occur, so they can prepare accordingly.

- Cons of the Product Life Cycle

- The product life cycle is too clean a picture. Sometimes a product’s sales might never rise beyond the introduction stage, or it may enter into a decline just before going into a subsequent rise. Consequently, this can cause managers to be too rigid in their strategies, as they expect the sales volumes of their products to follow a script written in stone.

- Product life cycles can be self-fulfilling. Each stage has a set of recommended actions. Consequently, when a product begins to behave as if it is in a decline, managers might decide to discontinue that product, because that is the protocol. Meanwhile, it could be that the product was merely dipping in sales, as a result of economic externalizations, which will eventually lift.

See Also

Product Lifecycle Management

Product

Product Data Management (PDM)

Product/Market Fit

Product/Market Grid

Application Lifecycle Management (ALM)

Application Lifecycle Framework

Software Development Life Cycle (SDLC)

References

- ↑ Definition - What is Product Life Cycle (PLC)? Shopify

- ↑ Significance of PLC Economics Times

- ↑ How Product Life Cycles Work Investopedia

- ↑ New Product Development Stages PLC Stages

- ↑ Product Life Cycle Stages Explained Quick MBA

- ↑ Preparing for the Product Life Cycle Patriot Software

- ↑ Product Life Cycle Management Living Better Media

- ↑ Closed-Loop Manufacturing Cycle SmartSheet

- ↑ The Mobile Apps PLC Nikola Draskovic et al.

- ↑ Product Life Cycle in Respect to The Technology Life Cycle urenio.org

- ↑ Product Life Cycle Examples productlifecyclestages.com

- ↑ Pyramid of Production Systems Wikipedia

- ↑ Criticisms of the PLC Know This

- ↑ Pros and Cons of the Product Life Cycle Chron

Further Reading

- The product life cycle : a critical look at the literature David M. Gardner

- Exploit the Product Life Cycle Theodore Levitt

- Product Life Cycle: the evolution of a paradigm and literature review from 1950-2009 Hui Cao and Paul Folan

- Application of late-stage product life cycle strategies by the medical device Industry - Thesis Kashif Ikram

- The Product Life Cycle: Analysis and Applications Issues George S Day