Affective Computing

Affective Computing is an emerging field of research that aims to enable intelligent systems to recognize, feel, infer and interpret human emotions. It is an interdisciplinary field which spans from computer science to psychology, and from social science to cognitive science. Though sentiment analysis and emotion recognition are two distinct research topics, they are conjoined under the field of Affective Computing research.[1]

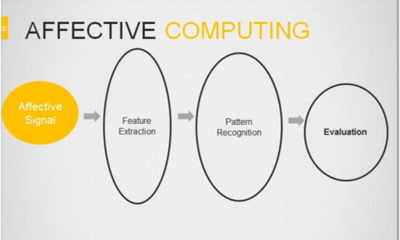

Affective computing technologies sense the emotional state of a user (via sensors, microphone, cameras and/or software logic) and respond by performing specific, predefined product/service features, such as changing a quiz or recommending a set of videos to fit the mood of the learner. The more computers we have in our lives the more we’re going to want them to behave politely, and be socially smart. We don’t want it to bother us with unimportant information. That kind of common-sense reasoning requires an understanding of the person’s emotional state. One way to look at affective computing is [[Human_Computer_Interaction_(HCI)|human-computer interaction in which a device has the ability to detect and appropriately respond to its user’s emotions and other stimuli. A computing device with this capacity could gather clues to user emotion from a variety of sources. Facial expressions, posture, gestures, speech, the force or rhythm of key strokes and the temperature changes of the hand on a mouse can all signify changes in the user’s emotional state, and these can all be detected and interpreted by a computer. A built-in camera captures images of the user and algorithms are used to process the data to yield meaningful information. Speech recognition and gesture recognition are among the other technologies being explored for affective computing applications. Recognizing emotional information requires the extraction of meaningful patterns from the gathered data. This is done using machine learning techniques that process different modalities, such as speech recognition, natural language processing, or facial expression detection.[2]

The Origins of Affective Computing[3]

The actual phrase, Affective Computing, was coined by Dr. Rosalind W Picard, who is the Director of Affective Computing Research at the MIT Affective Computing Research Group. She published a book entitled Affective Computing in 1997, and the name stuck, becoming the common term used for that field of computing. In her book, she looked in detail at how she envisioned affective computing would progress, as well as such areas as possible applications and potential concerns. Picard argued that there had to be something like emotional reasoning for there to be any form of true machine intelligence. Her key idea was that it should be possible to create machines that relate to, arise from, or deliberately influence emotion and other affective phenomena. She argued that programmers needed to consider affect when writing software that interacted with people. The roots of her vision of affective computing come from neurology, medicine, and psychology. It looks at the emotional interaction between people and machines from a biological perspective. According to Picard's school of thought, emotions (which are also known as affects), are identifiable states, which can be modelled to enable as human-like as possible interactions between people and machines. Since the late 1990s, many others have expanded on her theoretical ideas and quite a few of her ideas have over the last 20 years come into reality in practice. Her research is considered to be a cognitivistically-inspired design approach. Of course, as with most areas of scientific research, not all later researchers have agreed with Picard's ideas. This lack of total consensus in itself has helped advancement in the field, as more researchers have tried to expand on and provide proof for their personal theories. The best-known alternative is based on the Affective Interaction Approach. This approach focuses on making emotional experiences available for people to reflect upon which will in some way modify their reactions.

How Does Affective Computing Work?[4]

Affective computing captures signals from human users through cameras, microphones, skin sensors, or other means, collecting information about facial expression, voice tone, gestures, and other variables that can indicate emotional state. By evaluating those data points, the system interprets the user’s emotional state. That determination guides actions that the computing system takes, such as referring users to appropriate services or resources. An affective computing system might monitor an online learning environment, looking for signs of confusion or boredom among

learners and providing different learning choices for those who are struggling. In a sophisticated model that uses avatars or computer-generated voices to communicate with users, affective computing might tailor those avatars or voices to match or complement the emotions of the users. Affective computing software might expand to include mechanisms to “learn” over time, improving its ability to accurately recognize various emotions.

source:PAT Research

Applications of Affective Computing[5]

- Medical Applications: The detection of emotions by computers is very useful for medical applications, not only for the treatment of emotion-related problems, but also to ease the incorporation of emotional indicators as a diagnostic tool.

- Content Selection and Data Mining: The ability to detect the positiveness or satisfaction of a subject has lead to the improvement of recommendation systems and to develop more satisfactory content browsing systems.

- E-Learning: Affective Computing applications of emotion recognition can be very useful while overcoming the problems related to e-learning derived by the absence of human company.

- Interface Improvements: As mentioned, Human Computer Interaction is an area that highly benefits from improvements in affective computing. Interface improvement can be designed to better respond to the emotional state of the user.

- Neuromarketing: The ability to detect the emotional response of a human without the necessity of asking him or her has contributed to the development of neuromarketing, a discipline of marketing research that guides the design of products and marketing strategies according to the un-biased response of the subject.

Affective Computing: Critical Perspectives[6]

Mainstream affective computing is critically discussed, e.g., within the field of human-computer interaction. When Rosalind Picard coined the term 'affective computing', she outlined a cognitivist research program whose goal it is to " ... give computers the ability to recognize, express, and in some cases, 'have' emotions". A range of researchers have criticized this research program and outlined a post-cognitivist, "interactional" perspective which, as Kirsten Boehner and collaborators suggest, " ... take[s] emotion as a social and cultural product experienced through our interactions". They criticize the Picardian approach for its cognitivist notion of emotion that they also describe as an "information model" of emotion: Both cognition and emotion are construed here as inherently private and information-based: biopsychological events that occur entirely within the body. Like cognition, emotion can be modeled as a form of information processing, and another set of inputs to cognitive processing. This information account of emotion talks about it as a form of internal signaling, providing a context for cognitive action. The information model treats emotion as "objective, internal, private, and mechanistic". It reduces emotion to discrete psychological signal that is assumed to be formalizable and measurable in rather unproblematic ways. Critics of the Picardian approach to affective computing hold that such an understanding of emotion undercuts the complexity of emotional experience. The post-cognitive, interactional approach to affective computing departs from the Picardian research program in three ways: First, it adopts a notion of emotion as constituted in social interaction. This is not to deny that emotion has biophysical aspects, but it is to underline that emotion is "culturally grounded, dynamically experienced, and to some degree constructed in action and interaction". Second, the interactional approach does not seek to enhance the affect-processing capacities of computer systems. Rather, it seeks to help " ... people to understand and experience their own emotions".[52] Third, the interactional approach accordingly adopts different design and evaluation strategies than those described by the Picardian research program. Interactional affective design supports open-ended, (inter-)individual processes of affect interpretation. It recognizes the context-sensitive, subjective, changing and possibly ambiguous character of affect interpretation. And it takes into account that these sense-making efforts and affect itself may resist a computational formalization. To summarize, Picard and her adherents pursue a cognitivist measuring approach to users' affect, while the interactional perspective endorses a pragmatist approach that views (emotional) experience as inherently referring to social interaction. While the Picardian approach, thus, focuses on human-machine relations, interactional affective computing focuses primarily on computer-mediated interpersonal communication. And while the Picardian approach is concerned with the measurement and modeling of physiological variables, interactional affective computing is concerned with emotions as complex subjective interpretations of affect, arguing that emotions, not affect, are at stake from the point of view of technology users.

See Also

References

Further Reading

- What is Affective Computing And How Could Emotional Machines Change Our Lives?-Forbes

- The Encyclopedia of Human-Computer Interaction, 2nd Ed. 12. Affective Computing -Kristina Hook

- 7 Things You Should Know About Affective Computing -Educause

- Affective computing: How 'emotional machines' are about to take over our lives -The Telegraph

- Affective Computing: Challenges -Rosalind W. Picard