Organizational Change

Organizational Change is a process in which a large company or organization changes its working methods or aims, for example in order to develop and deal with new situations or markets: Sometimes deep organizational change is necessary in order to maintain a competitive edge.[1]

Organizational change is the process in which an organization changes its structure, strategies, operational methods, technologies, or organizational culture to affect change within the organization and the effects of these changes on the organization. Organizational change can be continuous or occur for distinct periods of time.[2]

Organizational Change looks at the process in which a company or any organization changes its operational methods, technologies, organizational structure, whole structure, or strategies, as well as what effects these changes have on it. Organizational change usually happens in response to – or as a result of – external or internal pressures. It is all about reviewing and modifying structures – specifically management structures – and business processes. Small commercial enterprises need to adapt to survive against larger competitors. They also need to learn to thrive in that environment. Large rivals need to adapt rapidly when a smaller, innovative competitor comes onto the scene. To avoid falling behind, or to remain a step ahead of its rivals, a business must seek out ways to operate more efficiently. It must also strive to operate more cost-effectively. Ever since the advent of the Internet, the business environment today has been changing at a considerably faster pace compared to forty years ago. Organizational change is a requirement for any business that wants to survive and thrive.[3]

Forces for Organizational Change[4]

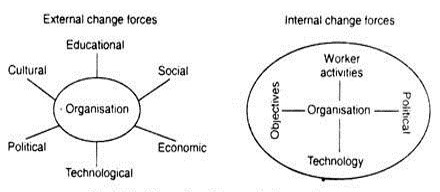

In practice, numerous factors affect an organization and most of these are continuously changing. These forces leading to or causing change to originate both within or outside the organization, as shown in the figure below.

source: Business Management Ideas

*External Change Forces:

External forces for change derive from the organization’s general and task environments. External forces causing changes may include technology, competition, government actions, economic variables, and social values. Government regulations on health, safety, and the conduct of business affect an organization. Labour laws influence hiring, pay, training, and promotion decisions. Tax laws change. Economic conditions- such as recession, money supply, inflation, and interest rates — are sources of change.

As Griffin has rightly put it:

“Changes in any of the elements of the general environment (that is, the economic, international, political, technological, and socio-cultural environments) or in the task environment (customers, competitors, associates, unions, regulatory, and suppliers) may necessitate a change in the organization itself. Change may also be brought about internally by a new manager or by the new philosophy of an existing manager.”

In the international element of the general environment, a foreign competitor (such as Canon) might introduce a new product, increase prices, reduce prices, change standards or enter new markets, thus forcing domestic organizations to react. In the political element, new laws, court decisions, and regulations all affect organizations. The technological element may yield new production techniques that the organization needs to explore.

Largely due to its proximity to the organization, the task environment usually is an even more powerful force for change. Competitors obviously influence organizations via their price structures and product lines. Customers determine what products can be sold at what prices. The organization must constantly be concerned with consumer tastes and preferences.

In a like manner, suppliers affect organizations by raising or lowering prices, changing product lines, or even snapping trade relations with a company. Regulators can have dramatic effects on an organization. Trade (labor) unions are a force for change when they demand and succeed in getting higher wages or going out on strike. Finally, subsidiaries can spur change as they add to or drain from the resource base of the holding company.

Finally, cultural changes in such areas as modes of dress, reasons for people working, the composition of the labor force, and changes in traditional female and male roles can affect the organizational environment. The sociocultural element, reflecting societal values, determines what kinds of products or services will find a ready market.

It appears that external change forces have a greater effect on organizational change than internal stimuli, as they are diverse and numerous and management has hardly any control over them.

*Internal Change Forces: Pressures for change may also originate from within the organization. In other words, various forces inside the organization may cause change. These forces might include managerial policies or styles, systems, and procedures; technology, and employee attitudes. For example, top management’s decision to shift its goal from long-term growth to short-term profit is likely to affect the goals of various departments and may even lead to re-organization. In short, if top management revises the organization’s goals, organizational change is likely to result.

A decision by Philips India Ltd. to enter the home computer market or a decision to increase a ten-year product sales goal by 3% would occasion many organization changes.

Other internal forces may actually be indirect reflections of external forces. As socio-cultural values shift, for example, workers’ attitudes toward their jobs may also shift and they may demand a change in working hours or working conditions. In such a case, even though the force is rooted in the external environment, the organization must respond directly to the internal pressure it generates. For example, the development of a new set of expectations for job performance will influence the values and behaviors of the employees affected. The employees could adapt to these expectations to resist them.

Types of Organizational Change[5]

With organizational change strategies, companies can avoid stagnation while minimizing disruption as much as possible. Preparation is integral for success, especially during a change effort. However, one can’t prepare without knowing what type of change is occurring. Here is a list of 5 types of organizational change companies may undergo.

- Organization-Wide Change: Organization-wide change is a large-scale transformation that affects the whole company. This could include restructuring the leadership, adding a new policy, or introducing enterprise technology, for example. Such a large-scale change will be felt by every single employee. However, as the dust settles, you can begin to see improvements. Sometimes change is required to see how a long-held policy has become outdated or that the company outgrew its shell. Like a hermit crab, leaders might identify the need to find a bigger shell for a better fit. However, poorly planned change can be highly disruptive and result in broad consequences across the company. Enterprise-wide change is quite extensive and needs to be planned with precision to protect all of those affected. Whether the results of the change are negative or positive depends on your organizational change strategies and their execution.

- Transformational Change: Transformational change specifically targets a company’s organizational strategy. Companies that are best suited to withstand the rapid change in their industry are nimble, adaptable, and prepared to transform their strategies when the need arises. Strategies to guide transformational change must account for the current situation and the direction a company plans on taking. Cultural trends, social climate, and technological progress are some of the many factors leaders must consider when devising organizational change strategies to support a transformation. According to a study from MIT Sloan Management Review and Deloitte, maturing digital businesses are focused on integrating digital technologies, such as social, mobile, analytics and cloud, into their transformation strategies. Meanwhile, less-mature digital businesses are focused on solving discrete business problems with individual technologies. However, given the rapid pace at which digital technology evolves, companies will be better positioned to succeed if they incorporate scalable and adaptable technology into their transformation strategies.

- Personnel Change: Personnel change is when a company implements mass hiring or layoffs. Each of these types of organizational change can cause a significant shift in employee morale and engagement, for better or worse. The threat of layoffs evokes fear and anxiety among staff members. Although certain circumstances necessitate such a decision, leaders should expect that employee morale will suffer. Nevertheless, the company must move forward. It is important to display genuine compassion and motivate employees to continue to work hard through difficult time. While mass hiring has better implications for a company, it is not without difficulty. Mass hiring is a sign of major growth, during which a company is susceptible to cultural changes and disorganization. Hiring new staff means training them, and providing ongoing support. Welcoming an influx of employees is great, but the work is cut out for those in management. If the transition is not handled correctly, it can cause chaos, and inefficiency, and ultimately deter further growth.

- Unplanned Change: Unplanned change is typically defined as necessary action following unexpected events. While unplanned change cannot be predicted — it can be dealt with in an organized manner. For example, the hurricanes that battered the U.S. early in the fall of 2017 caused thousands of residents to evacuate and seek temporary shelter far away from home. Following the emergency, they began the long process of restoring normalcy to their lives. Companies also experienced an unplanned change in the aftermath of the storms. New government regulations, over which individual companies have no control, can also spur unplanned change. Although the circumstances that lead to unplanned change may be chaotic, it’s important for organizations to be resilient and adaptable. Companies can also benefit from setting basic organizational change strategies in place to minimize chaos and disruption.

- Remedial Change: Leaders implement remedial changes when they identify a need to address deficiencies or poor company performance. For example, financial distress, usually due to poor performance, requires remedial change. The most common examples of such change could be introducing a new employee training program, rolling out a new software, or creating a new role to remedy a pain point. Other types of corrective action could include reviewing strategies that may have been in place for years but are no longer profitable. Issues stemming from leadership, such as a newly appointed CEO who turns out to be a poor fit for the company, might also call for remedial change. Although remedial change efforts must be tailored to the specific problem on hand, they still require effective organizational change strategies to be successful.

Theories on Organizational Change[6]

Theories on organizational change try to explain why organizations change and what the consequences of change might be (Barnett & Carroll, 1995). Based on the argumentation that understanding the theory and practice of change management is fundamental in order to achieve organizational effectiveness and success (Arnold et al., 2005), there are two approaches that in the last 50 years have dominated the theory, practice, and literature on change, and sheds light on the current debate on how to best manage change.

- The Planned approach to change. In 1946 Lewin, a pioneer in systematic studies of planned change (Kanter et al., 1992), initiated the Planned approach to change, which influenced and dominated the theory and practice of change management until the 1980s(Burnes, 2004). The Planned approach comprises Field theory, Group dynamics, Action research, and the Three-Step model, and the last one is cited as a key contribution to the study of organizational change. The Three-Step model for change recognizes that old behavior has to be discarded before any new behavior can be successfully adopted and fully accepted (Burnes, 1996). As indicated by the name, the process of planned change involves three steps: Unfreezing the present level, moving to the next level, and refreezing the new level. The Planned approach was primarily developed as a theoretical framework with a broad orientation toward understanding the concept of change in general, and not solely for organizational issues (Marcus, 2000). Nevertheless, Lewin’s Three-Step model is argued to be the best-developed, best-supported, and best-documented approach to change (Burnes, 2004), and its conceptualization is suggested as fundamental for understanding how humans and social systems change (Mirvis, 2006). Schein (2004) claims that any change in human systems is based on the assumptions originally derived from Lewin, and even those who have not read Lewin use the Planned approach (Kanter et al., 1992). The Planned approach influenced the field of organizational psychology, especially related to studies and theories on change, such as Beckhard and Harris’ Three-part process from 1987 explaining organizational change as a transition from a current to a future state (Marcus, 2000). The Organizational Development (OD) builds on the fundamental ideas of Lewin but argues that the Three-Step model should be seen as an independent rather than an integrated element in the Planned approach (Burnes, 2004). OD’s elaboration of the theory has resulted in alternative theories on planned change such as Lippitt and colleagues’ Seven-phase model from 1958, Bullock and Battens’ Four-phase model from 1985, and Cummings and Huses’ Eight-phase model from 1989. With a system-wide and humanistic-democratic orientation, OD received much attention as it responds to the changing needs of organizations and their customers (Arnold et al., 2005).

- The Emergent approach to change. The Planned approach to change received extensive criticism in the early 1980s regarding its inability to adapt to the rapid pace of change (Schein, 2004), and its focus on the small-scale and incremental change made it less applicable in large-scale and transformational change situations (Burnes, 1996). The description of organizations as frozen units that had to be refrozen was argued to be inappropriate, and the metaphor was argued to be replaced by the picture of organizations as fluid entities (Kanter et al., 1992). The Emergent approach appeared as several united stances against Lewinian, planned change, and became dominating due to its focus on organizations as complex, dynamic, and non-linear systems (Burnes, 2005), and it's understanding of the broad range of unpredictable problems facing modern organizations (Bamford & Forrester, 2003). Although focusing on organizational structure, organizational culture, organizational learning, managerial behavior, and power to politics (Burnes, 2004), and besides comprising Kotter’s (1996) Eight-Stage Process for Successful Organizational Transformation, and Kanter’s (Kanter et al., 1992) Ten Commandments for Executing Change, the Emergent approach is criticized for lacking coherence, being new in the game, and offering no more choice than the Planned approach (Burnes, 1996).

New paradigms and ‘no such thing as one way to change’. Based on the acceleration of change situations in the last two decades, and despite the large body of research devoted to the topic, there is still considerable disagreement concerning the most appropriate way to change. Research shows that the previously dominating approaches do not fully cover thespectrum of change confronting modern organizations (Burnes, 2004), no universal rule on how to successfully manage change exists (Dawson, 2003), and even currently available theories receive restricted support, and moderate empirical evidence (Bamford & Forrester, 2003; Burnes, 2004; Guimaraes & Armstrong, 1998; Todnem, 2005). Burnes (2004) moves beyond the question of good or bad approaches to change and calls for a more profound debate on appropriate models, as there is increasing support for rejecting the idea that one or two theoretical approaches are suitable for all change situations (O’Brien, 2002). The Contingency theory, emerging in the 1960s as one of the first theories to reject the ‘one best way’ approach of how to manage change, emphasizes that organizational activities are dependent on situational variables. As structure, strategies, culture, shape and size differ from organization to organization, the ‘one best way’ to change for all organizations should be replaced by the ‘one best way’ to change for each organization, seeking the optimum fit in each situation (Dunphy & Stace, 1993). A more recent contribution is Burnes Framework for Change (2004) that encompasses possible change situations and allows managers a degree of choice related to change under the given circumstances. The framework attempts to combine various approaches to change, as combining approaches on how to best assign change is suggested beneficial for organizational survival in the long run. In a similar vein, Cao, Clarke and Lehaney’s (2003) present a four-dimensional view on how to manage organizational change. Similar ideas are found when combining Beer and Nohria’s (2000) economicoriented Theory E with the human-oriented Theory O, or Kanter et al.’s (1992) suggestion that large-scale transformations of Bold Strokes should be followed by slow small-scale transformations of Long Marches, in order to embed and succeed with rapid change. Strategic organizational change comprises, according to Kotter (1996), small- and large-scale changes, and despite their different nature, starting time and management, the overall aim is the same.

A Model for Organizational Change[7]

A large global retailer uses the model illustrated below to increase the speed and impact of change initiatives while reducing the downturn of performance, thereby achieving desired outcomes quicker. This model for organizational change includes a four-phase change management process:

- Define—Align expectations regarding the scope of the change as well as timing and business impact.

- Plan—Understand how the change will impact stakeholders and design a strategy to help them navigate it.

- Implement—Engage with leaders and associates to execute the change.

- Sustain—Work with leaders and employees to track adoption and drive lasting change.

Process and Phases of Organizational Change[8]

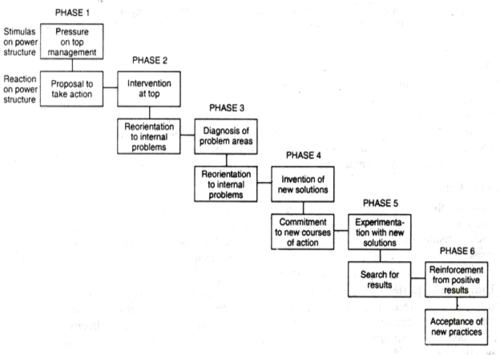

Understanding the process of change requires careful consideration of the steps in the change process, employee resistance to change, and how this resistance can be overcome. The management of change requires the use of some systematic process that can be divided into a few stages or sub-processes. This is the essence of the most representative model of managing change. It emphasizes the role of the change agent who is an outsider, taking a leadership role in initiating and introducing the process of change. The process of change must involve the following so as to lead to organizational effectiveness. Firstly, there is a re-distribution of power within the organizational structure. Secondly, this redistribution emanates from a developmental change process.

The figure below indicates that the process of change has to pass through six different phases

source: Business Management Ideas

- Internal pressure: The process of change begins as soon as top management starts feeling a need pressure for change from within the enterprise. This is usually caused by some significant problem(s) such as a sharp drop in sales (profits), serious labor trouble, and/or high labor turnover.

- Intervention and reorientation: An external agent is often invited to suggest a definition of the problem and start the process of getting organizational people to focus on it. If internal staff people are competent enough and can be trusted they can also manage the process of change equally well.

- Diagnosis and recognition of problem(s): The change agent and manager start gathering the necessary information and analyze it so as to recognize the more important problems and give attention to them.

- Invention of and commitment to solutions: It is important for the agent to stimulate thought and try to avoid using the ‘same old methods’. Solutions are searched out by creatively developing new and plausible alternatives. If subordinates are encouraged to participate in the process, they will develop a sense of involvement and are likely to be more committed to the course of action finally chosen.

- Experimentation and search for results: The solutions developed in phase 4 are normally put to test on a small scale (e.g., in pilot programs) and the results, are analyzed. If the solution is successful in one unit or a certain part of a unit, it may be tried in the organization as a whole.

- Reinforcement and acceptance: If the course of action is found desirable (after being properly tested), it should be accepted voluntarily by organization members. Improved performance should be the source of reinforcement and thus should lead to a commitment to the change.

Techniques for Effectively Managing Organizational Change[9]

Managing change effectively requires moving the organization from its current state to a future desired state at minimal cost to the organization. Key steps in that process are:

- Understanding the current state of the organization. This involves identifying problems the company faces, assigning a level of importance to each one, and assessing the kinds of changes needed to solve the problems.

- Competently envisioning and laying out the desired future state of the organization. This involves picturing the ideal situation for the company after the change is implemented, conveying this vision clearly to everyone involved in the change effort, and designing a means of transition to the new state. An important part of the transition should be maintaining some sort of stability; some things—such as the company's overall mission or key personnel—should remain constant in the midst of turmoil to help reduce people's anxiety.

- Implementing the change in an orderly manner. This involves managing the transition effectively. It might be helpful to draw up a plan, allocate resources, and appoint a key person to take charge of the change process. The company's leaders should try to generate enthusiasm for the change by sharing their goals and vision and acting as role models. In some cases, it may be useful to try for small victories first in order to pave the way for later successes.

Change is natural, of course. Proactive management of change to optimize future adaptability is invariably a more creative way of dealing with the dynamism of industrial transformation than letting them happen willy-nilly. That process will succeed better with the help of the company's human resources than without.

Challenges to Organizational Change[10]

Organizations only do two things: change and stay the same. It's the organizations that change who own the future. Change isn't easy. The ability to change is one of the biggest differences between organizations. It's the reason some companies can innovate — while others seem endlessly stuck in the same old patterns. The following barriers to change are fundamental business gravity. Reduce these barriers and you'll effortlessly move forward. Let these barriers get out of control and you'll sink like a rock.

- Resistance to Change: People resist change (status quo bias). In fact, many people are willing to accept lower pay to get into an organization that's stable (an organization that seldom changes). Resistance to change often has political motives. People tend to resist changes that originate with political adversaries. Another reason that people resist change is that they simply think the change is going to make their life worse (e.g. complicate their job). People may resist change directly (e.g. use political influence) or indirectly (e.g. passive-aggressive behavior).

- Unknown Current State: An architect wouldn't renovate a building without looking at the existing blueprints. The culture, processes, and systems of large organizations dwarf the complexity of a building's architecture. Nevertheless, organizations often attempt change without an examination of their current blueprints. This makes it difficult to transition to a future state.

- Integration: Managing changes in a large organization has been compared to re-engineering an aircraft while it's in flight. Change is always a moving target. As you implement a system the business processes it supports will change. As you change an organizational structure, employee turnover will occur in parallel. Long running changes that have many integration points are extremely failure-prone.

- Competitive Forces: In many cases, external forces drive organizational change. Competition, external threats, technological change, market conditions, and economic forces are all common drivers of change. Organizations may expedite change in response to external threats. If a competitor releases a product that's 5 years ahead of your products — you may be driven to an extreme pace of change that has a high risk of failure.

- Complexity: As organizations develop more complex processes, systems, and products — change becomes more challenging. The complexity of change is a fundamental barrier. Complex changes require a diligent and highly effective project, risk, quality, knowledge, and change management. In many cases, organizations simply lack the requisite maturity to tackle a complex change. A fundamental principle of change management is to never tackle a change that's too complex for your organization.

Benefits of Organizational Change[11]

Change is scary, but change is good when it causes companies to rethink how they operate, find ways to increase efficiencies, explore new market opportunities and so much more. Among the many perks of organizational changes can be:

- Innovation: In adapting, it’s possible to find new income strategies or create new products that can bolster the bottom line and grow the company.

- Diversification: When seizing whatever opportunities may come out of a changing playing field, a company may find itself having to pursue new markets, new partners and/or new audiences. It may be a struggle at first, but if successful, the company may find itself on even more solid ground than before.

- Improved communication: Being forced to change can make management seek input from team members who are normally overlooked. By inviting participation, communication can improve, and it can also spark increased teamwork.

As companies face obstacles like having to implement change due to external forces, it’s easy for employees to panic if they feel the company's been backed into a corner for whatever reason. Overcoming those obstacles, though, can help the company grow stronger not just from a market standpoint but also thanks to improved morale. When a company proves to be resilient, employees have increased optimism for job security and greater respect for management, which can ultimately reduce turnover. Also, having to adapt to market forces means potentially unearthing new talents and leadership from existing employees who may step up to take on new roles as the scenario progresses. By listening to employee ideas and suggestions, it's possible for management to discover who's been overlooked and underutilized for too long. Being forced to change can really be one of the best things to ever happen to a company, but it all comes down to whether the management proves to be innovative and adaptable when that's needed.

See Also

References

- ↑ Defining Organizational Change Cambridge Dictionary

- ↑ What is Organizational Change? Study.com

- ↑ The Need for Organizational Change MBN

- ↑ What are the External and Internal Forces for Organizational Change? Business Management Ideas

- ↑ What are some of the Different Types of Organizational Change? WalkMe

- ↑ Theories on Organizational Change Ellen Flakke

- ↑ A Four Step Model for Organizational Change SHRM

- ↑ Process and Phases of Organisational Change Manvi Sharma

- ↑ Techniques for Effectively Managing Organizational Change Inc.com

- ↑ What are the Barriers to Organizational Change? Simplicable

- ↑ Benefits of Organizational Change Bizfluent