Difference between revisions of "Theory of Planned Behavior"

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | The ''' | + | The '''Theory of Planned Behavior''' is a theory used to understand and predict behaviors, which posits that behaviors are immediately determined by behavioral intentions and under certain circumstances, perceived behavioral control. Behavioral intentions are determined by a combination of three factors: attitudes toward the behavior, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control.<ref>Definition - What Does the Theory of Planned Behavior Mean? [https://link.springer.com/referenceworkentry/10.1007%2F978-3-319-28099-8_1191-1 Matthew P. H. Kan, Leandre R. Fabrigar]</ref> |

The theory of planned behavior (TPB) has been used successfully to explain and predict behavior in a multitude of behavioral domains, from physical activity to drug use, from recycling to choice of travel mode, from safer sex to consumer behavior, and from technology adoption to protection of privacy, to name but a few (for meta‐analytic syntheses of some of this research, see e.g., Albarracin, Fishbein, & Goldestein de Muchinik, 1997; Armitage & Conner, 1999; Hagger, Chatzisarantis, & Biddle, 2002; Hirschey et al., 2020; McDermott et al., 2015; Riebl et al., 2015; Winkelnkemper, Ajzen, & Schmidt, 1919). The following description of the TPB is adapted from Ajzen and Kruglanski (2019). | The theory of planned behavior (TPB) has been used successfully to explain and predict behavior in a multitude of behavioral domains, from physical activity to drug use, from recycling to choice of travel mode, from safer sex to consumer behavior, and from technology adoption to protection of privacy, to name but a few (for meta‐analytic syntheses of some of this research, see e.g., Albarracin, Fishbein, & Goldestein de Muchinik, 1997; Armitage & Conner, 1999; Hagger, Chatzisarantis, & Biddle, 2002; Hirschey et al., 2020; McDermott et al., 2015; Riebl et al., 2015; Winkelnkemper, Ajzen, & Schmidt, 1919). The following description of the TPB is adapted from Ajzen and Kruglanski (2019). | ||

| Line 16: | Line 16: | ||

Previous investigations have shown that a person's behavior is strongly influenced by the individual's confidence in his or her ability to perform that behavior. As self-efficacy contributes to explanations of various relationships among beliefs, attitudes, intentions, and behavior, TPB has been widely applied in health-related fields such as helping preadolescents to engage in more physical activity, thereby improving their mental health, and getting adults to exercise more. | Previous investigations have shown that a person's behavior is strongly influenced by the individual's confidence in his or her ability to perform that behavior. As self-efficacy contributes to explanations of various relationships among beliefs, attitudes, intentions, and behavior, TPB has been widely applied in health-related fields such as helping preadolescents to engage in more physical activity, thereby improving their mental health, and getting adults to exercise more. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | == Constructs of the Theory of Planned Behavior<ref>The Six Constructs of the Theory of Planned Behavior [https://sphweb.bumc.bu.edu/otlt/mph-modules/sb/behavioralchangetheories/BehavioralChangeTheories3.html Boston University]</ref> == | ||

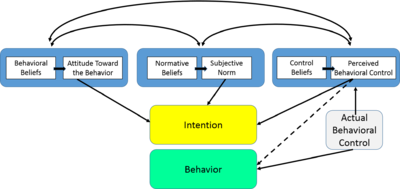

| + | The theory of planned behavior (TPB) has been used successfully to explain and predict behavior in a multitude of behavioral domains, from physical activity to drug use, from recycling to choice of travel mode, from safer sex to consumer behavior, and from technology adoption to protection of privacy, to name but a few (for meta‐analytic syntheses of some of this research, see e.g., Albarracin, Fishbein, & Goldestein de Muchinik, 1997; Armitage & Conner, 1999; Hagger, Chatzisarantis, & Biddle, 2002; Hirschey et al., 2020; McDermott et al., 2015; Riebl et al., 2015; Winkelnkemper, Ajzen, & Schmidt, 1919). The following description of the TPB is adapted from Ajzen and Kruglanski (2019). The TPB states that behavioral achievement depends on both motivation (intention) and ability (behavioral control). It distinguishes between three types of beliefs - behavioral, normative, and control. The TPB is comprised of six constructs that collectively represent a person's actual control over the behavior. | ||

| + | *Attitudes - This refers to the degree to which a person has a favorable or unfavorable evaluation of the behavior of interest. It entails a consideration of the outcomes of performing the behavior. | ||

| + | *Behavioral intention - This refers to the motivational factors that influence a given behavior where the stronger the intention to perform the behavior, the more likely the behavior will be performed. | ||

| + | *Subjective norms - This refers to the belief about whether most people approve or disapprove of the behavior. It relates to a person's beliefs about whether peers and people of importance to the person think he or she should engage in the behavior. | ||

| + | *Social norms - This refers to the customary codes of behavior in a group or people or larger cultural context. Social norms are considered normative, or standard, in a group of people. | ||

| + | *Perceived power - This refers to the perceived presence of factors that may facilitate or impede performance of a behavior. Perceived power contributes to a person's perceived behavioral control over each of those factors. | ||

| + | *Perceived behavioral control - This refers to a person's perception of the ease or difficulty of performing the behavior of interest. Perceived behavioral control varies across situations and actions, which results in a person having varying perceptions of behavioral control depending on the situation. This construct of the theory was added later, and created the shift from the Theory of Reasoned Action to the Theory of Planned Behavior. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | [[File:Theory of Planned Behavior.png|400px|Theory of Planned Behavior]]<br /> | ||

| + | source: Boston University | ||

Revision as of 13:53, 5 May 2021

The Theory of Planned Behavior is a theory used to understand and predict behaviors, which posits that behaviors are immediately determined by behavioral intentions and under certain circumstances, perceived behavioral control. Behavioral intentions are determined by a combination of three factors: attitudes toward the behavior, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control.[1]

The theory of planned behavior (TPB) has been used successfully to explain and predict behavior in a multitude of behavioral domains, from physical activity to drug use, from recycling to choice of travel mode, from safer sex to consumer behavior, and from technology adoption to protection of privacy, to name but a few (for meta‐analytic syntheses of some of this research, see e.g., Albarracin, Fishbein, & Goldestein de Muchinik, 1997; Armitage & Conner, 1999; Hagger, Chatzisarantis, & Biddle, 2002; Hirschey et al., 2020; McDermott et al., 2015; Riebl et al., 2015; Winkelnkemper, Ajzen, & Schmidt, 1919). The following description of the TPB is adapted from Ajzen and Kruglanski (2019).

Theory of Planned Behavior - Historical Background[2]

Extension from the theory of reasoned action

Icek Ajzen (1985) proposed TPB in his chapter "From intentions to actions: A theory of planned behavior." TPB developed out of Theory of Reasoned Action, a theory first proposed in 1980 by Martin Fishbein and Ajzen. TRA was in turn grounded in various theories bearing on attitude and attitude change, including learning theories, expectancy-value theories, attribution theory, and consistency theories (e.g., Heider's balance theory, Osgood and Tannenbaum's congruity theory, and Festinger's dissonance theory). According TRA, if an individual evaluates a suggested behavior as positive (attitude), and if he or she believes significant others want the person to perform the behavior (subjective norm), the intention (motivation) to perform the behavior will be greater and the individual will be more likely to perform the behavior. Attitudes and subjective norms are highly correlated with behavioral intention; behavioral intention is correlated with actual behavior.

Research, however, shows that behavioral intention does not always lead to actual behavior. Because behavioral intention cannot be the exclusive determinant of behavior where an individual's control over the behavior is incomplete, Ajzen introduced TPB by adding to TRA the component "perceived behavioral control." In this way he extended TRA to better predict actual behavior.

Perceived behavioral control refers to the degree to which a person believes that he or she can perform a given behavior. Perceived behavioral control involves the perception of the individual's own ability to perform the behavior. In other words, perceived behavioral control is behavior- or goal-specific. That perception varies by environmental circumstances and the behavior involved. The theory of planned behavior suggests that people are much more likely to intend to enact certain behaviors when they feel that they can enact them successfully. The theory has thus improved upon TRA.

Extension of self-efficacy

Along with attitudes and subjective norms (which make up TRA), TPB adds the concept of perceived behavioral control, which grew out of self-efficacy theory (SET). The construct of self-efficacy was proposed by Bandura in 1977, in connection to social cognitive theory. Self-efficacy refers to a person's expectation or confidence that he or she can master a behavior or accomplish a goal; an individual has different levels of self-efficacy depending upon the behavior or goal in question. Bandura distinguished two distinct types of goal-related expectations: self-efficacy and outcome expectancy. He defined self-efficacy as the conviction that one can successfully execute the behavior required to produce the outcome in question. Outcome expectancy refers to a person's estimation that a given behavior will lead to certain outcomes. Bandura advanced the view that self-efficacy is the most important precondition for behavioral change, since it is key to the initiation of coping behavior.

Previous investigations have shown that a person's behavior is strongly influenced by the individual's confidence in his or her ability to perform that behavior. As self-efficacy contributes to explanations of various relationships among beliefs, attitudes, intentions, and behavior, TPB has been widely applied in health-related fields such as helping preadolescents to engage in more physical activity, thereby improving their mental health, and getting adults to exercise more.

Constructs of the Theory of Planned Behavior[3]

The theory of planned behavior (TPB) has been used successfully to explain and predict behavior in a multitude of behavioral domains, from physical activity to drug use, from recycling to choice of travel mode, from safer sex to consumer behavior, and from technology adoption to protection of privacy, to name but a few (for meta‐analytic syntheses of some of this research, see e.g., Albarracin, Fishbein, & Goldestein de Muchinik, 1997; Armitage & Conner, 1999; Hagger, Chatzisarantis, & Biddle, 2002; Hirschey et al., 2020; McDermott et al., 2015; Riebl et al., 2015; Winkelnkemper, Ajzen, & Schmidt, 1919). The following description of the TPB is adapted from Ajzen and Kruglanski (2019). The TPB states that behavioral achievement depends on both motivation (intention) and ability (behavioral control). It distinguishes between three types of beliefs - behavioral, normative, and control. The TPB is comprised of six constructs that collectively represent a person's actual control over the behavior.

- Attitudes - This refers to the degree to which a person has a favorable or unfavorable evaluation of the behavior of interest. It entails a consideration of the outcomes of performing the behavior.

- Behavioral intention - This refers to the motivational factors that influence a given behavior where the stronger the intention to perform the behavior, the more likely the behavior will be performed.

- Subjective norms - This refers to the belief about whether most people approve or disapprove of the behavior. It relates to a person's beliefs about whether peers and people of importance to the person think he or she should engage in the behavior.

- Social norms - This refers to the customary codes of behavior in a group or people or larger cultural context. Social norms are considered normative, or standard, in a group of people.

- Perceived power - This refers to the perceived presence of factors that may facilitate or impede performance of a behavior. Perceived power contributes to a person's perceived behavioral control over each of those factors.

- Perceived behavioral control - This refers to a person's perception of the ease or difficulty of performing the behavior of interest. Perceived behavioral control varies across situations and actions, which results in a person having varying perceptions of behavioral control depending on the situation. This construct of the theory was added later, and created the shift from the Theory of Reasoned Action to the Theory of Planned Behavior.

- ↑ Definition - What Does the Theory of Planned Behavior Mean? Matthew P. H. Kan, Leandre R. Fabrigar

- ↑ History of the Theory of Planned Behavior Wikipedia

- ↑ The Six Constructs of the Theory of Planned Behavior Boston University