Brainstorming

Brainstorming is one of the most creative ways of problem-solving in which we work on ideas. We can either come up with a new idea or build on an existing idea as well. Since there is no rule of thumb in brainstorming, it can be applied individually or in a group.

- Firstly, a goal is defined to understand what the main purpose of brainstorming is.

- Once we have an end goal to achieve or a problem to solve, various challenges that come along are explored.

- Furthermore, different aspects of the problem or situation are explored and we list down ways to overcome the challenges.

- There is no structure in brainstorming, and no idea is considered wrong. All ideas are noted during the brainstorming sessions, and some can even be clubbed together.

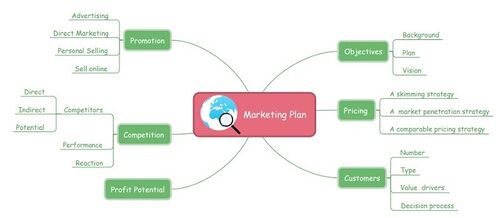

Let’s consider that you need to work on a marketing plan for your brand. Firstly, you will define its objective and the vision of the brand. Subsequently, you will work on other things like the promotional strategy, what the customers think, the pricing, and what your competitors are doing. After considering all these things in mind, you can come up with a new and exciting marketing plan.[1]

Origin of Brainstorming

Advertising executive Alex F. Osborn began developing methods for creative problem-solving in 1939. He was frustrated by employees’ inability to develop creative ideas individually for ad campaigns. In response, he began hosting group-thinking sessions and discovered a significant improvement in the quality and quantity of ideas produced by employees. He first termed the process as organized ideation and was later dubbed by participants as "brainstorm sessions", taking the concept after the use of "the brain to storm a problem." During the period when Osborn made his concept, he started writing on creative thinking, and the first notable book where he mentioned the term brainstorming is "How to Think Up" in 1942. Osborn outlined his method in the 1948 book Your Creative Power in chapter 33, "How to Organize a Squad to Create Ideas".

One of Osborn's key recommendations was for all the members of the brainstorming group to be provided with a clear statement of the problem to be addressed prior to the actual brainstorming session. He also explained that the guiding principle is that the problem should be simple and narrowed down to a single target. Here, brainstorming is not believed to be effective in complex problems because of a change in opinion over the desirability of restructuring such problems. While the process can address the problems in such a situation, tackling all of them may not be feasible.

The Principles of Brainstorming[2]

While brainstorming has evolved over the years, Osborne’s four underlying principles are a great set of guidelines when running your own sessions. These principles include:

- Quantity over quality. The idea is that quantity will eventually breed quality as ideas are refined, merged, and developed further.

- Withhold criticism. Team members should be free to introduce any and all ideas that come into their heads. Save feedback until after the idea collection phase so that “blocking” does not occur.

- Welcome the crazy ideas. Encouraging your team members to think outside of the box, and introduce pie-in-the-sky ideas opens the door to new and innovative techniques that may be your ticket to success.

- Combine, refine, and improve ideas. Build on ideas, and draw connections between different suggestions to further the problem-solving process.

Brainstorming Considerations[3]

- When possible, have a separate facilitator and recorder. The facilitator should act as a buffer between the group and the recorder(s), keeping the flow of ideas going and ensuring that no ideas get lost before being recorded. The recorder should focus on capturing the ideas.

- The recorder should try not to rephrase ideas. If an idea is not clear, ask for a rephrasing that everyone can understand. If the idea is too long to record, work with the person who suggested the idea to come up with a concise rephrasing. The person suggesting the idea must always approve of what is recorded.

- Keep all ideas visible. When ideas overflow to additional flipchart pages, post previous pages around the room so all ideas are still visible to everyone.

- The more ideas the better. Studies have shown that there is a direct relationship between the total number of ideas and the number of beneficial, creative ideas.

- Allow for and encourage creative, unconventional, and out-of-the-box ideas.

- Don’t be afraid to piggyback or build on someone else’s idea.

Individual Brainstorming Vs. Group Brainstorming[4]

Individual Brainstorming

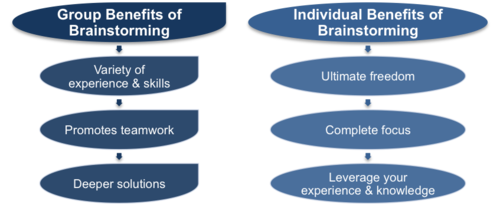

While group brainstorming is often more effective at generating ideas than normal group problem-solving, several studies have shown that individual brainstorming produces more – and often better – ideas than group brainstorming.

This can occur because groups aren't always strict in following the rules of brainstorming, and bad behaviors creep in. Mostly, though, this happens because people pay so much attention to other people that they don't generate ideas of their own – or they forget these ideas while they wait for their turn to speak. This is called "blocking."

When you brainstorm on your own, you don't have to worry about other people's egos or opinions, and you can be freer and more creative. For example, you might find that an idea you'd hesitate to bring up in a group develops into something special when you explore it on your own.

However, you may not develop ideas as fully when you're on your own, because you don't have the wider experience of other group members to draw on.

Individual brainstorming is most effective when you need to solve a simple problem, generate a list of ideas, or focus on a broad issue. Group brainstorming is often more effective for solving complex problems.

Some of the key benefits of individual brainstorming are as follows –

- Ultimate freedom. Even when all members of a group are instructed to be as supportive as possible, there is still bound to be some judgment and criticism within the process. That won’t be a problem with individual brainstorming, however, as you will be free to record any and all ideas that come to mind.

- Rather than being distracted by the conversation and activity of the group as a whole, you can focus in on the task at hand when you brainstorm on an individual basis.

- Leverage your experience. If you have detailed experience with a specific problem that needs to be solved, it may be best to brainstorm solutions to that problem all on your own. After all, you have the experience and knowledge necessary, so it should be just a matter of time until you find a proper solution.

source: Free Management e-Books

Group Brainstorming

Here, you can take advantage of the full experience and creativity of all team members. When one member gets stuck with an idea, another member's creativity and experience can take the idea to the next stage. You can develop ideas in greater depth with group brainstorming than you can with individual brainstorming.

Another advantage of group brainstorming is that it helps everyone feel that they've contributed to the solution, and it reminds people that others have creative ideas to offer. It's also fun, so it can be great for team building!

Group brainstorming can be risky for individuals. Unusual suggestions may appear to lack value at first sight – this is where you need to chair sessions tightly so that the group doesn't crush these ideas and stifle creativity.

Where possible, participants should come from a wide range of disciplines. This cross-section of experience can make the session more creative. However, don't make the group too big: as with other types of teamwork, groups of five to seven people are usually the most effective.

Of course, there are plenty of benefits to be noted when talking about group brainstorming as well, such as the points on the list below –

- Variety of backgrounds. When brainstorming as a group, you will have access to the various experiences of all members of the group, so you will be more likely to stumble on a quality idea or solution. An idea that may have been missed by an individual brainstorming just may be found by the group.

- Promote teamwork. Every organization can benefit from bringing its team together to work toward a common goal. By having a productive team brainstorming session from time to time, you will be able to build morale and allow everyone to feel like they are having input in the process.

- Deeper solutions. Once someone within the group brainstorming session comes across a good idea, others in the group may be able to expand on the idea in order to come up with a thorough, complex answer to the problem at hand.

The Importance of Brainstorming[5]

- Invites Diverse Viewpoints: In any business, when a single person is responsible for generating all of your ideas, those ideas are likely to become stale or repetitive at some point. During a brainstorming session, however, you can collect ideas from a number of others. Those ideas may not be brilliant or even viable, but as you brainstorm together your ideas may evolve into something that is fresh and effective. Since your coworkers or associates likely have diverse backgrounds, interests, and motivations, they can offer unique perspectives, says the Millennium Agency.

- Encourages Critical Thinking: Harvard Business Review suggests that brainstorming is important because it requires team members to think critically to solve a certain problem or create something innovative. The more you brainstorm, the better you become at encountering a problem and thinking about it critically. This means taking a topic or situation and looking at it in a logical and clear way, free from personal bias. Critical thinking may require you to break a topic or problem down into smaller parts. For instance, if you need to form a campaign around a new product, you’ll need to consider various pieces of the campaign, like product packaging, advertising mediums, and messaging.

- Sparks Creativity: When you need to be creative, your own brain can become your worst enemy. That’s because creative thoughts may get jumbled and confused in your head, preventing you from thinking them through clearly. You also may come up with a vague idea, but find yourself unable to get the idea to take definite shape. The benefits of brainstorming include an opportunity to pull the jumbled ideas from your head and get them out – either audibly or on paper. Seeing or discussing these ideas can help you give them detail and shape, increasing the likelihood of finding something innovative, suggests Entrepreneur.

- Supports Team Building: When you practice brainstorming as a group, you take team ownership of a campaign, product, or event. This means that one person isn’t left feeling like he is carrying the workload for the entire company, and also cultivates a feeling of team ownership. Groups that practice brainstorming together may also learn how to work together better. The advantages of brainstorming sessions will enable you to see certain talents or expertise in your coworkers of which you weren’t aware, which can be a great advantage when you need help in the future.

Brainstorming Techniques[6]

Basic Brainstorming isn't complex — though there are important techniques for ensuring success. While this process may be simple in theory, it’s not always easy to generate new ideas out of nowhere. And that’s why so many interesting and inspirational brainstorming techniques have been developed.

- Analytic Brainstorming: When brainstorming focuses on problem-solving, it can be useful to analyze the problem with tools that lead to creative solutions. Analytic brainstorming is relatively easy for most people because it draws on idea-generation skills they’ve already built in school and in the workplace. No one gets embarrassed when asked to analyze a situation!

- Mind Mapping: Mind mapping is a visual tool for enhancing the brainstorming process. In essence, you’re drawing a picture of the relationships among and between ideas. Start by writing down your goal or challenge and ask participants to think of related issues. Layer by layer, add content to your map so that you can visually see how, for example, a problem with the telephone system is contributing to issues with quarterly income. Because it's become so popular, it's easy to find mind-mapping software online. The reality, though, is that a large piece of paper and a few markers can also do the job.

- Reverse Brainstorming: Ordinary brainstorming asks participants to solve problems. Reverse brainstorming asks participants to come up with great ways to cause a problem. Start with the problem and ask “how could we cause this?” Once you've got a list of great ways to create problems, you’re ready to start solving them!

- Gap Filling: Start with a statement of where you are. Then write a statement of where you’d like to be. How can you fill in the gap to get to your goal? Your participants will respond with a wide range of answers from general to particular. Collect them all, and then organize them to develop a vision for action.

- Drivers Analysis: Work with your group to discover the drivers behind the problem you’re addressing. What’s driving client loyalty down? What’s driving the competition? What’s driving a trend toward lower productivity? As you uncover the drivers, you begin to catch a glimpse of possible solutions.

- SWOT Analysis: SWOT Analysis identifies the organization's strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats. Usually, it’s used to decide whether a potential project or venture is worth undertaking. In brainstorming, it’s used to stimulate collaborative analysis. What are our real strengths? Do we have weaknesses that we rarely discuss? New ideas can come out of this tried-and-true technique.

- The Five Whys: Another tool that’s often used outside of brainstorming, the Five Whys can also be effective for getting thought processes moving forward. Simply start with a problem you’re addressing and ask “why is this happening?” Once you've got some answers, ask “why does this happen?” Continue the process five times (or more), digging deeper each time until you’ve come to the root of the issue.

- Starbursting: Create a six-pointed star. At the center of the star, write the challenge or opportunity you’re facing. At each point of the star, write one of the following words: who, what, where, when, why, and how. Use these words to generate questions. Who are our happiest clients? What do our clients say they want? Use the questions to generate discussion.

- Quiet Brainstorming: In some situations, individuals are so cramped for the time that a brainstorming session would be impossible to schedule. In other situations, team members are unwilling to speak up in a group or to express ideas that others might not approve of. When that’s the case, you might be well served with brainstorming techniques that allow participants to generate ideas without meeting or without the need for public participation.

- Brain-Netting (Online Brainstorming): Perhaps not surprisingly, brain netting involves brainstorming on the Internet. This requires someone to set up a system where individuals can share their ideas privately, but then collaborate publicly. There are software companies that specialize in just such types of systems, like Slack or Google Docs. Once ideas have been generated, it may be a good idea to come together in person, but it’s also possible that online idea generation and discussion will be successful on its own. This is an especially helpful approach for remote teams to use, though any team can make use of it.

- Brainwriting (or Slip Writing): The brainwriting process involves having each participant anonymously write down ideas on index cards. The ideas can then be randomly shared with other participants who add to or critique the ideas. Or, the ideas can be collected and sifted by the management team. This approach is also called “Crawford Slip Writing,” as the basic concept was invented in the 1920s by a professor named Crawford.

- Collaborative Brainwriting: Write your question or concern on a large piece of paper and post it in a public place. Ask team members to write or post their ideas when they're able, over the course of a week. Collate ideas on your own or with your group's involvement.

- Role Play Brainstorming: What do customers/clients/managers really want? What are the challenges we face internally or externally? Very often, those questions are best answered by internal and external clients. Role play allows your team to “become” their own clients, which often provides surprisingly potent insights into challenges and solutions. Another plus of role play is that, in some cases, it lowers participants’ inhibitions. Variants of role play include Rolestorming, Reverse Thinking, and Figure Storming.

- Role Storming: Ask your participants to imagine themselves in the role of a person whose experience relates to your brainstorming goal (a client, upper management, or a service provider). Act out a scene, with participants pretending to take the other’s point of view. Why might they be dissatisfied? What would it take for them to feel better about their experience or outcomes?

- Reverse Thinking: This creative approach asks, “what would someone else do in our situation?” Then imagine doing the opposite. Would it work? Why or why not? Does the “usual” approach really work well, or are there better options?

- Figure Storming: Choose a figure from history or fiction with whom everyone is familiar—Teddy Roosevelt, for example, or Mother Theresa. What would that individual do to manage the challenge or opportunity you’re discussing? How might that figure’s approach work well or poorly?

- Brainstorming With Support: For groups that aren't creative or communicative or are likely to get stuck once the most obvious ideas have been suggested, help is in order. You can provide that help up front by setting up the brainstorming process to include everyone in a structured, supportive manner. A few techniques for this type of brainstorming include Step Ladder Brainstorming, Round Robin Brainstorming, Rapid Ideation, and Trigger Storming.

- Step Ladder Brainstorming: Start by sharing the brainstorming challenge with everyone in the room. Then send everyone out of the room to think about the challenge—except two people. Allow the two people in the room to come up with ideas for a short period of time, and then allow just one more person to enter the room. Ask the new person to share their ideas with the first two before discussing the ideas already generated. After a few minutes ask another person to come in, and then another. In the long run, everyone will be back in the room—and everyone will have a chance to share his or her ideas with colleagues.

- Round Robin Brainstorming: A “round robin” is a game in which everyone gets a chance to take part. That means everyone:

- must share an idea and

- wait until everyone else has shared before suggesting a second idea or critiquing ideas

- This is a great way to encourage shy (or uninterested) individuals to speak up while keeping dominant personalities from taking over the brainstorming session.

- Rapid Ideation: This simple technique can be surprisingly fruitful. Ask the individuals in your group to write down as many ideas as they can in a given period of time. Then either have them share the ideas aloud or collect responses. Often, you’ll find certain ideas popping up over and over. In some cases, these are the obvious ideas. But in some cases, they may provide some revelations.

- Trigger Storming: This variant of the round-robin approach starts with a “trigger” to help people come up with thoughts and ideas. Possible triggers include open-ended sentences or provocative statements. For example, “Client issues always seem to come up when ____,” or “The best way to solve client problems is to pass the problem along to someone else.”

- Radically Creative Brainstorming: If your team seems to be stuck on conventional answers to brainstorming challenges, you may need to stir the pot to help them generate creative ideas by using techniques that need out-of-the-box thinking. These may include the Charrette approach and "what if" challenges.

- Charrette: Imagine a brainstorming session in which 35 people from six different departments are all struggling to come up with viable ideas. The process is time-consuming, boring, and—all too often—unfruitful. The Charrette method breaks up the problem into smaller chunks, with small groups discussing each element of the problem for a set period of time. Once each group has discussed one issue, their ideas are passed on to the next group who builds on them. By the end of the Charrette, each idea may have been discussed five or six times—and the ideas discussed have been refined.

- "What If" Brainstorming: What if this problem came up 100 years ago? How would it be solved? What if Superman were facing this problem? How would he manage it? What if the problem were 50 times worse—or much less serious than it really is? What would we do? These are all different types of “what if” scenarios that can spur radically creative thinking—or at least get people laughing and working together!

Electronic Brainstorming[7]

Although brainstorming can take place online through commonly available technologies such as email or interactive websites, there have also been many efforts to develop customized computer software that can either replace or enhance one or more manual elements of the brainstorming process.

Early efforts, such as GroupSystems at the University of Arizona or Software Aided Meeting Management (SAMM) system at the University of Minnesota, took advantage of then-new computer networking technology, which was installed in rooms dedicated to computer-supported meetings. When using these electronic meeting systems (EMS, as they came to be called), group members simultaneously and independently entered ideas into a computer terminal. The software collected (or "pools") the ideas into a list, which could be displayed on a central projection screen (anonymized if desired). Other elements of these EMSs could support additional activities such as the categorization of ideas, elimination of duplicates, and assessment and discussion of prioritized or controversial ideas. Later EMSs capitalized on advances in computer networking and internet protocols to support asynchronous brainstorming sessions over extended periods of time and in multiple locations.

Introduced along with the EMS by Nunamaker and colleagues at the University of Arizona was electronic brainstorming (EBS). By utilizing customized computer software for groups (group decision support systems or groupware), EBS can replace face-to-face brainstorming. An example of groupware is GroupSystems, a software developed by the University of Arizona. After an idea discussion has been posted on GroupSystems, it is displayed on each group member's computer. As group members simultaneously type their comments on separate computers, those comments are anonymously pooled and made available to all group members for evaluation and further elaboration.

Compared to face-to-face brainstorming, not only does EBS enhance efficiency by eliminating traveling and turn-taking during group discussions, but it also excluded several psychological constraints associated with face-to-face meetings. As identified by Gallupe and colleagues, both production blocking (reduced idea generation due to turn-taking and forgetting ideas in face-to-face brainstorming) and evaluation apprehension (a general concern experienced by individuals for how others in the presence are evaluating them) are reduced in EBS. These positive psychological effects increase with group size. A perceived advantage of EBS is that all ideas can be archived electronically in their original form, and then retrieved later for further thought and discussion. EBS also enables much larger groups to brainstorm on a topic than would normally be productive in a traditional brainstorming session.

Computer-supported brainstorming may overcome some of the challenges faced by traditional brainstorming methods. For example, ideas might be "pooled" automatically, so that individuals do not need to wait to take a turn, as in verbal brainstorming. Some software programs show all ideas as they are generated (via chat room or e-mail). The display of ideas may cognitively stimulate brainstormers, as their attention is kept on the flow of ideas being generated without the potential distraction of social cues such as facial expressions and verbal language. EBS techniques have been shown to produce more ideas and help individuals focus their attention on the ideas of others better than a brainwriting technique (participants write individual written notes in silence and then subsequently communicate them with the group). The production of more ideas has been linked to the fact that paying attention to others' ideas leads to non-redundancy, as brainstormers try to avoid replicating or repeating another participant's comment or idea. Conversely, the production gain associated with EBS was less found in situations where EBS group members focused too much on generating ideas that they ignored ideas expressed by others. The production gain associated with GroupSystem users' attentiveness to ideas expressed by others has been documented by Dugosh and colleagues. EBS group members who were instructed to attend to ideas generated by others outperformed those who were not in terms of creativity.

According to a meta-analysis comparing EBS to face-to-face brainstorming conducted by DeRosa and colleagues, EBS has been found to enhance both the production of non-redundant ideas and the quality of ideas produced. Despite the advantages demonstrated by EBS groups, EBS group members reported less satisfaction with the brainstorming process compared to face-to-face brainstorming group members.

Some web-based brainstorming techniques allow contributors to post their comments anonymously through the use of avatars. This technique also allows users to log on over an extended time period, typically one or two weeks, to allow participants some "soak time" before posting their ideas and feedback. This technique has been used particularly in the field of new product development, but can be applied in any number of areas requiring the collection and evaluation of ideas.

Some limitations of EBS include the fact that it can flood people with too many ideas at one time that they have to attend to, and people may also compare their performance to others by analyzing how many ideas each individual produces (social matching).

The Pros and Cons of Brainstorming[8]

There are many advantages to brainstorming, and it can be used in any industry to solve most problems where a solution may not always be obvious.

Pros

The main benefits include:

- Discovering new perspectives: Brainstorming gives vision and perspective where these elements may not have existed before. It encourages free speech and creativity, helping to reveal new ideas and solutions.

- Defining problems: Spontaneous thinking in a low-pressure environment can often help to define a problem to the point where new alternative

- Equal participation: Brainstorming helps to avoid conflict and to give everybody a chance to air their views without immediate evaluation or judgment. In a brainstorming session, everybody should have an equal opportunity to participate in the discussion.

Cons

The main pitfalls include:

- Time-consuming: The brainstorming process can take time. It could be hours, or even days before a solution is reached.

- Utopian Ideas: Sometimes the ideas suggested are unworkable.

- Wiseacres: Colleagues may refuse to consider others' ideas or outvoice others.

- Facilitator required: Brainstorming requires a leader or facilitator who will take control of the session and ensure it reaches a satisfactory conclusion.

Brainstorming needs to be approached in the right way in order to be effective. The good news, however, is that the advantages far outweigh any disadvantages.

See Also

References

- ↑ Definition - What Does Brainstorming Mean?

- ↑ The four principles of brainstorming

- ↑ Brainstorming Considerations

- ↑ Individual Brainstorming Vs. Group Brainstorming

- ↑ Why is Brainstorming Important

- ↑ 19 Top Brainstorming Techniques to Generate Ideas for Every Situation

- ↑ Electronic Brainstorming

- ↑ The Pros and Cons of Brainstorming