Confirmation Bias

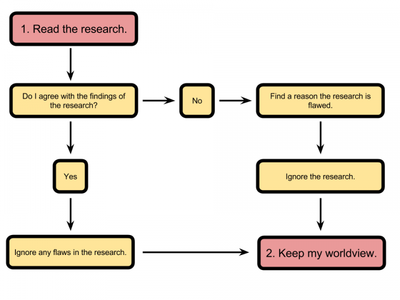

Confirmation Bias occurs from the direct influence of desire on beliefs. When people would like a certain idea/concept to be true, they end up believing it to be true. They are motivated by wishful thinking. This error leads the individual to stop gathering information when the evidence gathered so far confirms the views (prejudices) one would like to be true. Once having formed a view, individuals embrace information that confirms that view while ignoring, or rejecting, information that casts doubt on it. Confirmation bias suggests that we don’t perceive circumstances objectively. We pick out those bits of data that make us feel good because they confirm our prejudices. Thus, we may become prisoners of our assumptions.[1]

Types of Confirmation Bias[2]

Confirmation biases are effects in information processing. They differ from what is sometimes called the behavioral confirmation effect, commonly known as self-fulfilling prophecy, in which a person's expectations influence their own behavior, bringing about the expected result. Some psychologists restrict the term confirmation bias to selective collection of evidence that supports what one already believes while ignoring or rejecting evidence that supports a different conclusion. Others apply the term more broadly to the tendency to preserve one's existing beliefs when searching for evidence, interpreting it, or recalling it from memory.

- Biased Search for Information: Experiments have found repeatedly that people tend to test hypotheses in a one-sided way, by searching for evidence consistent with their current hypothesis. Rather than searching through all the relevant evidence, they phrase questions to receive an affirmative answer that supports their theory. They look for the consequences that they would expect if their hypothesis were true, rather than what would happen if they were false. For example, someone using yes/no questions to find a number he or she suspects to be the number 3 might ask, "Is it an odd number?" People prefer this type of question, called a "positive test", even when a negative test such as "Is it an even number?" would yield exactly the same information. However, this does not mean that people seek tests that guarantee a positive answer. In studies where subjects could select either such pseudo-tests or genuinely diagnostic ones, they favored the genuinely diagnostic.

- Biased Interpretation: Confirmation biases are not limited to the collection of evidence. Even if two individuals have the same information, the way they interpret it can be biased. A team at Stanford University conducted an experiment involving participants who felt strongly about capital punishment, with half in favor and half against it. Each participant read descriptions of two studies: a comparison of U.S. states with and without the death penalty, and a comparison of murder rates in a state before and after the introduction of the death penalty. After reading a quick description of each study, the participants were asked whether their opinions had changed. Then, they read a more detailed account of each study's procedure and had to rate whether the research was well-conducted and convincing. In fact, the studies were fictional. Half the participants were told that one kind of study supported the deterrent effect and the other undermined it, while for other participants the conclusions were swapped. The participants, whether supporters or opponents, reported shifting their attitudes slightly in the direction of the first study they read. Once they read the more detailed descriptions of the two studies, they almost all returned to their original belief regardless of the evidence provided, pointing to details that supported their viewpoint and disregarding anything contrary. Participants described studies supporting their pre-existing view as superior to those that contradicted it, in detailed and specific ways.

- Biased Memory: Even if people gather and interpret evidence in a neutral manner, they may still remember evidence selectively to reinforce their expectations. This effect is called "selective recall", "confirmatory memory", or "access-biased memory". Psychological theories differ in their predictions about selective recall. Schema theory predicts that information matching prior expectations will be more easily stored and recalled than information that does not match. Some alternative approaches say that surprising information stands out and so is memorable. Predictions from both these theories have been confirmed in different experimental contexts, with no theory winning outright. In one study, participants read a profile of a woman which described a mix of introverted and extroverted behaviors. They later had to recall examples of her introversion and extroversion. One group was told this was to assess the woman for a job as a librarian, while a second group were told it was for a job in real estate sales. There was a significant difference between what these two groups recalled, with the "librarian" group recalling more examples of introversion and the "sales" groups recalling more extroverted behavior. A selective memory effect has also been shown in experiments that manipulate the desirability of personality types. In one of these, a group of participants were shown evidence that extroverted people are more successful than introverts. Another group were told the opposite. In a subsequent, apparently unrelated, study, they were asked to recall events from their lives in which they had been either introverted or extroverted. Each group of participants provided more memories connecting themselves with the more desirable personality type, and recalled those memories more quickly.

Avoiding Confirmation Bias[3]

- Take It All in; Don’t Jump to Conclusions: Treat the initial data-gathering stage as a fact-finding mission, without trying to understand the specific causes of any identified fluctuations. That is, resist the temptation to immediately generate potential hypotheses. Wait until a more complete information set has been reviewed. Only then begin to consider reasons the data may differ from expectations.

- Brainstorming: The Rule of Three: If possible, identify three potential causes for each unexpected data fluctuation that is identified. Why is three the magic number? Research has shown that auditors who develop three hypotheses are more likely to correctly identify misstatements when performing analytical procedures than those who develop just one hypothesis. From a probabilistic standpoint, the more plausible the expectations brainstormed, the higher the likelihood that the underlying cause of the fluctuation will be identified. However, developing too many initial hypotheses may constrain the auditor’s ability to efficiently evaluate each potential explanation. Research published in the Journal of Accounting Research in 1999 revealed that auditors who develop three hypotheses are actually more efficient, and just as effective, at identifying misstatements through the use of analytical procedures as those who develop more than three hypotheses.

- Flag It: When identifying potential causes of a financial fluctuation, take note of the specific information that triggered a hypothesis. Present those data to a colleague to see whether he or she comes up with similar explanations. If the explanations are different, the colleague has assisted you in expanding your hypothesis set. If the explanations are similar, the colleague has provided you with some validation of your existing set. In other words, two minds can improve your chances of identifying the true explanation for the fluctuation.

- Prove Yourself Wrong: Once an initial set of hypotheses has been developed, it’s natural to seek out evidence that confirms these explanations. However, accepting evidence as support ignores the fact that the same evidence could also indicate a different explanation. In a similar fashion, it’s also common to subconsciously ignore contradictory evidence. This is the heart of confirmation bias. Instead, try to disconfirm your initial suspicions by actively seeking out and weighing contradictory information. Such an approach can only lead to stronger and more definitive conclusions.

- Circle Back: After identifying your initial hypotheses, the next required step is to investigate the data further to determine which (if any) is the actual cause of the data fluctuation. While performing this investigation, additional information will invariably be analyzed to confirm or disconfirm these explanations. Don’t forget to revisit old hypotheses and consider fresh ones when examining these new data. Remember that successful hypothesis generation during the performance of analytical procedures is an iterative process. Suspicions may or may not be confirmed by using these five steps in an audit, but you’ll have certainty about two preconceptions: You’ll have avoided the pitfall of confirmation bias, and you’re far more likely to have discovered the true cause of financial fluctuations.

source: AB Tasty

Challenges of Confirmation Bias[4]

Confirmation bias can create problems for investors. When researching an investment, someone might inadvertently look for information that supports his or her beliefs about an investment and fail to see information that presents different ideas. The result is a one-sided view of the situation. Confirmation bias can thus cause investors to make poor decisions, whether it’s in their choice of investments or their buy-and-sell timing. For example, suppose an investor hears a rumor that a company is on the verge of declaring bankruptcy. Based on that information, the investor is considering selling the stock. When he goes online to read the latest news about the company, he tends to read only the stories that confirm the likely bankruptcy scenario and he misses a story about the new product the company just launched that is expected to perform extremely well. Instead of holding the stock, he sells it at a substantial loss just before it turns around and climbs to an all-time high. Confirmation bias is a source of investor overconfidence and helps explain why bulls tend to remain bullish and bears tend to remain bearish regardless of what is actually happening in the market. Confirmation bias helps explain why markets do not always behave rationally. However, an investor who is aware of confirmation bias may be able to overcome the tendency to seek out information that supports his existing opinions and intentionally seek out contradictory advice.

Blame it on Confirmation Bias[5]

Over the years the confirmation bias has picked up the blame for all sorts of dodgy beliefs. Here are a few:

- People are prejudiced (partly) because they only notice facts which fit with their preconceived notions about other nations or ethnicities.

- People believe weird stuff about flying saucers, the JFK assassination, astrology, Egyptian pyramids and the moon landings because they only look for confirmation not dis-confirmation.

- In the early nineteenth century doctors treated any old disease with blood-letting. Their patients sometimes got better so doctors—who conveniently ignored all the people who died—figured it must be doing something. In fact for many ailments some people will always get better on their own without any treatment at all.

See Also

References

- ↑ What is Confirmation Bias? Psycholoday Today

- ↑ Types of Confirmation Bias Wikipedia

- ↑ How to Avoid the Pitfalls of Confirmation Bias Babson.edu

- ↑ Breaking Down Confirmation Bias Investopedia

- ↑ Blaming it on Confirmation Bias PsyBlog

Further Reading

- Confirmation Bias: A Ubiquitous Phenomenon in Many Guises Raymond S. Nickerson

- Confirmation Bias and Art Samuel McNerney

- Confirmation bias in science: how to avoid it Ars Technica