Employability

Professor Mantz Yorke of the University of Edinburgh defines Employability as "a set of achievements – skills, understandings and personal attributes – that make individuals more likely to gain employment and be successful in their chosen occupations, which benefits themselves, the workforce, the community, and the economy."[1]

Other Definitions of Employability[2]

- (Hillage and Pollard, 1998): "Employability is the capability to move self-sufficiently within the labor market to realize potential through sustainable employment. For the individual, employability depends on the knowledge, skills, and attitudes they possess, the way they use these assets and present them to employers, and the context (personal circumstances and labor market environment) within which they seek work." They propose employability consists of four elements:

- employability assets (knowledge, skills, attitudes)

- deployment (career management skills)

- presentation (job-getting skills, CV, interview technique, etc)

- personal circumstances (who you are, responsibility, labor market, etc).

- Anneleen Forrier; Luc Sels (2003): "Employability is the ability to maintain employment and make 'transitions' between jobs and roles within the same organization to meet new job requirements."

- Van der Heijde and Van der Heijden (2005): "Employability is the ability to obtain new employment if required, i.e. to be independent in the labor market by being willing and able to manage their own employment transitions between and within organizations. The continuously fulfilling, acquiring or creating of work through the optimal use of efforts."

- Erik Berntson (2008): "Employability is the ability to gain initial employment; hence the interest in ensuring that 'key competencies', careers advice and an understanding about the world of work are embedded in the education system." Berntson argues that employability refers to an individual's perception of his or her possibilities of getting new, equal, or better employment. Berntson's study differentiates employability into two main categories – actual employability (objective employability) and perceived employability (subjective employability).

- Lee Harvey, former Director of the Centre for Research and Evaluation at Sheffield Hallam University, defines employability "as the ability of a graduate to get a satisfying job", stating that job acquisition should not be prioritized over preparedness for employment to avoid a pseudo measure of individual employability. Lee argues that employability is not a set of skills but a range of experiences and attributes developed through higher-level learning, thus employability is not a "product' but a process of learning.

Models of Employability[3]

- Hillage and Pollard (1998, p. 2) suggest that: In simple terms, employability is about being capable of getting and keeping fulfilling work. More comprehensively employability is the capability to move self-sufficiently within the labour market to realise potential through sustainable employment. They propose that employability consists of four main elements.

- The first of these, a person’s “employability assets”, consists of their knowledge, skills and attitudes.

- The second, “deployment”, includes career management skills, including job search skills.

- Thirdly, “presentation” is concerned with “job getting skills”, for example CV writing, work experience and interview techniques.

- Finally, Hillage and Pollard (1998) also make the important point that for a person to be able to make the most of their “employability assets”, a lot depends on their personal circumstances (for example family responsibilities) and external factors (for example the current level of opportunity within the labour market).

- Bennett et al. (1999) proposed a model of course provision in higher education which included five elements:

- (1) disciplinary content knowledge;

- (2) disciplinary skills;

- (3) workplace awareness;

- (4) workplace experience; and

- (5) generic skills.

This model goes some way towards including all the necessary elements to ensure a graduate achieves an optimum level of employability, but is still missing some vital elements

- The USEM account of employability (Yorke and Knight, 2004; Yorke and Knight, 2004) is probably the most well known and respected model in this field. USEM is an acronym for four inter-related components of employability:

- (1) understanding;

- (2) skills;

- (3) efficacy beliefs; and

- (4) metacognition

The authors suggest that behind the USEM model is:

... an attempt to put thinking about employability on a more scientific basis, partly because of the need to appeal to academic staff on their own terms by referring to research evidence and theory” (Knight and Yorke, 2004, p 37).

The USEM model forms part of a large body of research-based scholarly work on employability. However, this strength could also be perceived as a weakness, in that it does not assist in explaining to non-experts in the field, particularly the students themselves and their parents, exactly what is meant by employability.

- The Centre for Employability (CfE) at the University of Central Lancashire (UCLan) in the UK has been developing practical solutions to enhance the prospects of students and graduates for over ten years. As a consequence of the careers service origins of this unit, the main theoretical model that has underpinned this work has been the DOTS model (Law and Watts, 1977), which consists of: ... planned experiences designed to facilitate the development of:

- Decision learning – decision making skills

- Opportunity awareness – knowing what work opportunities exist and what their requirements are

- Transition learning – including job searching and self presenting skills

- Self awareness – in terms of interests, abilities, values, etc. (Watts, 2006, pp. 9-10).

The value of this model lies in its simplicity, as it allows individuals to organise a great deal of the complexity of career development learning into a manageable framework. However, the model has recently attracted some criticism. McCash (2006) argues that the model is over-reliant on a mechanistic matching of person and environment, and therefore underplays other critical issues such as social and political contexts. He also points out that there is an implication that failure to secure a “self-fulfilling” occupation can be presented, or experienced, as the fault of the unsuccessful individual. These criticisms overlook the fact that the elegant simplicity of the DOTS model is precisely why it has proved so enduring and popular. They also seem to suggest that students introduced to basic concepts of career development through DOTS would be incapable of developing and learning about more sophisticated analyses through this simple introductory structure.

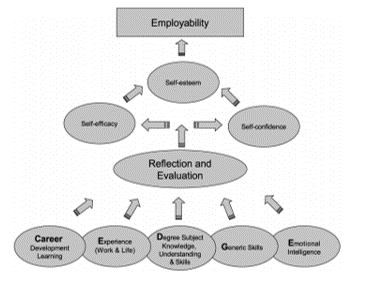

The CareerEDGE Model of Employability[4]

The CareerEDGE model of graduate employability was introduced in 2007. Since that time it has been received extremely positively, both nationally and internationally. Other models of employability were in existence before the introduction of CareerEDGE (some are mentioned in this article) but were considered either too elaborate to be practically useable or too simple to capture the meaning of this somewhat elusive concept. The mnemonic CareerEDGE is used as an aid to remember the five lower tier components of the model and it is suggested that students should be provided with opportunities to develop all of these components. CareerEDGE highlights that it is essential that students are given opportunities to reflect on and evaluate these experiences, to develop higher levels of self-efficacy, self-confidence and self esteem; crucial links to employability.

One intention of developing the model was to avoid the mistaken belief that when we use the term ‘employability’ we are just concerned with ‘employment’ or are just talking about developing the ‘skills’ that many employers now expect to see in graduate recruits. Although these are important aspects of employability they are not the complete picture. Using the model can be helpful when explaining that employability is involved with the much broader development of students into graduates who feel ready and prepared for whatever life holds for them beyond university. As Hallett (2012) states,

‘It is refreshing to think that ‘employability’ might grow into something broader than a particular set of skills and competencies, into a richer idea of graduate readiness …’ (p30).

The Key Components of CareerEDGE Model

The key components of the CareerEDGE model highlight what are considered to be the most important facets of ‘employability’, including career development learning, experience, degree subject knowledge, skills and understanding, generic skills and emotional intelligence.

source: Lorraine Darcre Pool, Peter Sewell

- CAREER DEVELOPMENT LEARNING (CDL): CDL in the context of Higher Education has been described as being ‘… concerned with helping students to acquire knowledge, concepts, skills and attitudes which will equip them to manage their careers, ie their lifelong progression in learning and in work.’ (Watts, 2006, p2). Learning a selection of ‘job getting’ skills, such as writing an effective CV, completing a job application or presenting yourself in an interview, is incorporated in this element but in itself forms only one aspect of CDL. By providing students with support and guidance that enables them to develop their self-awareness, who they are and what they want from their future lives, and to consider what opportunities (local, national and global) are out there for them, we will help them to make more informed decisions. Included here could be activities that encourage students to consider if self-employment is something they might wish to explore. We can also help them to prepare for a competitive graduate labour market by ensuring they know how best to articulate how their time within HE has enabled them to develop both personally and professionally into the graduate recruits potential employers are looking for. As with all elements of CareerEDGE, CDL is an essential component. A student may gain an excellent degree classification and develop many of the skills employers are looking for, but if they are unable to decide what type of occupation they would find satisfying or are unaware of how to articulate their knowledge and skills to a prospective employer, they are unlikely to achieve their full career potential.

- EXPERIENCE – WORK AND LIFE: Another element from the lower tier of the CareerEDGE model is that of ‘experience’. This includes work experience but, importantly for many students, other life experiences too. Harvey (2005) contends that, in particular, younger, full-time students who have not had significant work experience as part of their programmes of study often leave university with very little idea of the nature and culture of the workplace and consequently can find it difficult to adjust. There is also research which suggests that graduates with work experience are more likely to gain employment upon graduation than those without (Pedagogy for Employability Group, 2006). Other research has found overwhelming evidence for the value of work-based and work-related learning experiences in promoting the employability of graduates (Lowden, Hall, Elliot & Lewin, 2011). The necessity for students to gain work experience now seems to be accepted by employers and most HE staff alike. Indeed this was one of the major points made by the Wilson Review of Business-University Collaboration (2012). Most universities have recognised this thinking and have staff dedicated to helping students to engage with some form of work-related learning. For many students this will not only allow them to develop the professional skills expected in all graduate recruits, but may also allow them to think about how the theory and knowledge they are gaining through their degree studies can be related to the real world. They will also be able to incorporate these real-life experiences into their studies and hopefully see how the theory and real-world experience can contribute to their overall understanding of their academic discipline.

- DEGREE SUBJECT KNOWLEDGE, SKILLS AND UNDERSTANDING: This has always been and remains at the heart of CareerEDGE. Students come to university to learn about a particular subject – some with a view to gaining work within this field, others purely because they are passionate about developing their knowledge and understanding of the subject. It is arguable that we all want our students to gain the most from their studies, to develop a love of learning and gain the best degree classification they can.

- GENERIC SKILLS (INCLUDING ENTERPRISE SKILLS): Although it has been argued that the skills approach alone is insufficient to do justice to the much broader concept of graduate employability (eg Tomlinson, 2012), employers do understand the language of skills and are often quite specific about the skills they expect to see in graduate recruits. As they also attempt to measure these in their recruitment and selection processes, it is difficult to argue that we should not be providing our students with knowledge of these requirements together with opportunities to develop these skills whilst at university. Many of the generic skills listed by employers as vital in graduate recruits, such as communication, team working, problem solving, digital literacy and many more, including those sometimes classified as ‘enterprise skills’ such as creativity and innovation, are also skills that will help students to make the most of their academic studies. As such, they can often be developed within the HE curriculum; but students do need to be made aware of when this is happening, which can be done through ensuring these are included as learning outcomes. This way students are able to see how they are developing the skills and competencies employers are looking for and will be able to offer evidence of these when applying for work experience opportunities and/or graduate jobs.

- EMOTIONAL INTELLIGENCE: This might have been one of the more controversial elements within CareerEDGE but all of the feedback received since 2007 has been distinctly positive. Emotional Intelligence ability is something that has a significant effect on relationships and well-being (eg Mayer, Roberts & Barsade, 2008) and as such deserves a place within any model of graduate employability. It is also a desirable attribute for potential leaders (Walter, Cole & Humphrey, 2011) which many graduates aspire to become. EI ability is concerned with how people perceive, understand and manage emotion; a graduate who is unable to pay attention to their own and others feelings, understand those feelings and manage them effectively is likely to experience difficulties in their personal relationships and their professional relationships with colleagues, managers and customers. Therefore it is important to make students aware of this and help them to develop their ability in this area. Again, activities to help with this kind of development can be, and in many cases already are, incorporated into the curriculum. Any activities that encourage students to work together, communicate effectively, negotiate with each other and reflect on their learning experiences, can be used to develop EI ability. There are many opportunities to include such activities in most HE curricula and research has demonstrated that it is possible for students to improve their EI ability together with confidence in that ability (Dacre Pool & Qualter, 2012). It can also be helpful to include activities in other related areas such as diversity and cultural awareness, both of which require us to consider how our words and actions can impact on the feelings of others.

- Reflection and evaluation: Providing students with the opportunities to gain the necessary skills, knowledge, understanding and personal attributes through employability related activities is obviously of great importance. However, without opportunities to reflect on these activities and evaluate them, it is unlikely that this experience will transfer into learning. This type of reflective learning often takes the form of written learning logs or reflective journals but could also include audio, video and e-portfolios. Reflection can help a student to gain employment by providing a means by which they can become aware of and articulate their abilities. But additionally it is an ability that will help them in their employment (many roles now call for reflective practitioners) and as a contributor to lifelong learning skills; as such it is an essential element both in relation to HE learning and in the employment context (Moon, 2004). It is also through the process of reflection and evaluation that our students are able to develop their self-efficacy, self-confidence and self-esteem – crucial links to employability.

The CareerEDGE model is helpful for explaining the concept of employability to students, enabling them to take responsibility for their own employability development. It can also be helpful to inform the planning of programs and structured interventions by providing clarity of information about what needs to be considered and included. Importantly, it can serve as a clear, practical framework to help all who work in HE to unite in their common objective of supporting students to develop into well-rounded, employable graduates.

See Also

References

- ↑ Definition - What Does Employability Mean? University of Edinburgh

- ↑ Overview of Employability Wikipedia

- ↑ Models of Employability Lorraine Darcre Pool, Peter Sewell

- ↑ The CareerEDGE Model of Graduate Employability Yorkforum.org