IT Capability

IT Capability (information technology capability) refers to an organization’s ability to identify IT to meet business needs, to deploy IT to improve business processes in a cost-effective manner and to provide long-term maintenance and support for IT-based systems (Karimi et al., 2007). It is the ability to leverage different IT resources for intangible benefits.[1]

Information Technology (IT) Capability is an organization’s ability, by virtue of its IT assets and know-how, to create Business Value.

This capability can be, and is usually, attributed to the IT function within an organization. More appropriately, it should be attributed to the organization as a whole because no function within an organization is an island. Each gain from the other and, in turn, enriches them. This value “bleed” from one function to another cannot be quantified meaningfully. However, it exists. It can be positive or negative. When the organization plays as a team, i.e., the functions collaborate, positive value passes between functions. In this case, the organization’s capability is greater than the sum of its parts. The functions are better off together. Conversely, when the organization does not play as a team, i.e., is dysfunctional, the value bleed is negative. In this case, the organization’s capability is less than the sum of its parts. It follows that the functions are better off not being with each other! The net of this phenomenon is that no function within an organization would create the same value within another organization. For example, suppose an IT organization is moved from one company to another. In that case, it will deliver more or less but never the same value as it was created in the original company. This is true of any team. You may have noticed that a player is successful or more successful on one team versus the other.

IT capability, a measure of an organization's proficiency in leveraging technology to achieve business objectives, is deeply intertwined with the expertise and guidance of the Chief Information Officer (CIO). Beyond the mere deployment of technological resources, IT capability encompasses the integration, optimization, and strategic use of technology to drive innovation and competitive advantage. At the forefront of this endeavor is the CIO, who crafts a roadmap that melds technological potential with business goals. In an evolving digital landscape, the differentiation between an organization's IT capability and its core operational success has become almost indistinguishable. As a result, the role of the CIO in sculpting and enhancing this capability is paramount. Their strategic decisions, insights into emerging technologies, and leadership in fostering IT agility and resilience often determine the height of the organization's IT capability and, by extension, its market position.

Components of IT Capability (Figure 1.)

IT Capability is comprised of four sub-components or elements. IT’s overall capability is not the sum total but the synthesis of capabilities of its underlying elements.

Figure 1. Source: CIO Portal

IT Capability comprises the following components:

- IT Strategy

- IT Processes and Metrics

- IT Organization

- Skills

- Structure

- Knowledge/“know-how”

- Assets/Infrastructure

- Hardware

- Software

- Application

- Network

- Database

- Tools

An organization creates value by utilizing a unique combination and configuration of these components.

Mapping IT Capabilities to Business Capabilities[2]

From a strategy perspective, the Business Capability analysis is based on the current definition of functions instead of an organizational structure, as the organizational structure is quite dynamic and frequent changes, which may create a chaotic process model, use the value chain or the supply/demand governance model to map the business capability.

- A pragmatic approach is to look at this from a 'value streams' perspective:

- Identify major business value streams (end-to-end processes that deliver customer value).

- Map information technology-related services that support these or are missing (untapped capability).

- Estimate the 'capability leverage,' preferably in dollars, provided, or potentially so, by each of these IT services to each value stream (greater agility, etc.).

- Estimate the business capability (preferably normalized to dollars) represented by each value stream

- Map IT capabilities to either:

- What the business does - Capabilities or

- How the business does it - Processes\Functions

- Processes are best if you are working at a tactical level

- Capabilities are best for strategic work

Either will help identify business/IT alignment issues

- One Page IT Capability Mapping: It is quite interesting if everything can be put on one page. It depends on the nature of the enterprise (diversified), its size, and the age of the enterprise as well. So single page would include fundamental to any business enterprise the questions of ‘what do we do', and ‘how do we do it':

- Vision

- Requirements to deliver

- IT capability

- The resources, metrics, applications, and information associated with capabilities aggregate all the resources, metrics, etc., belonging to the business processes that 'work for' the capabilities.

The approach could be to draw an enterprise value chain and expose all the business capabilities beneath those functions and highlight the activities & identify the overlaps and gaps, then take it to the next level (with lots of details) on multiple pages. For all the capabilities, calculate the cost in three categories strategic, operational, and governance. For all the foundational capabilities like HR, finance, and others, draw that at the bottom of the sheet across the whole enterprise value chain.

Defining Required IT Capabilities[3]

Every organization's needs are different: Some need IT to focus on delivering the latest and greatest applications, while others need IT to create a robust infrastructure. Let's accept one fact: IT is a service provider, and the firm and its employees are its customers. IT must enable the business and ensure that its customers are satisfied with the basic services (for example, keeping servers and email up and running and providing help-desk support) and that all IT operations are efficient and cost-effective. Creating a strategic IT vision requires determining the IT organization's various customer segments and business needs. Generally, customers need a set of capabilities across a range of functions. Typically these capabilities fall into three main areas. Each of these areas must be optimized by the IT organization:

- IT operational excellence. Critical capabilities that allow IT assets to be managed to take information systems to higher levels of effectiveness and cost efficiency. The objective is to create low-cost, flexible support for the enterprise.

- Business enablement and process improvement. The ability to transform or improve core business processes within the organization. The goal of core-value and IT-enabling processes is to take value chains and business operations to world-class levels. The measure of success does not cost reduction but improvements to key business processes.

- IT innovation. Solutions developed with the business to help achieve breakthrough innovation to improve competitiveness. Initiatives move beyond improving processes to helping create competitive strategies and transforming market dynamics, repositioning a company against its competitors, or allowing it to enter markets where it did not previously compete.

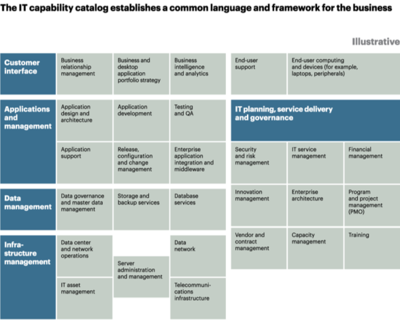

IT capabilities can be illustrated in a capability catalog, establishing a common language and framework for services to be consumed and delivered to the business (see Figure 2). Additionally, the capability catalog can be used as a basis to define which capabilities are core and which are non-core.

Figure 2. source: A.T. Kearney

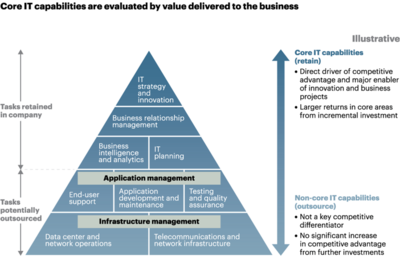

Core capabilities are those for which in-house expertise must be developed because they are often critical to the business and for gaining a competitive advantage. Examples include business relationship management and IT strategy and innovation. Non-core capabilities are less crucial to be executed by in-house staff and are often outsourced to IT services providers. Potential examples often include end-user support, application development, and infrastructure management (see figure ).

Figure 3. source: A.T. Kearney

Potential Landscape of IT Capabilities (Figure 4.)[4]

Below is a diagrammatic illustration of a normative, high-level IT Capability Model. One can debate the specific labels for each of these capabilities, but essentially, any enterprise that depends upon Information Technology to any degree needs each of these IT Capabilities.

Principles at the platform may expose potential capability gaps, such as a lack of data in the forms the business unit will require or insufficient IT skills to support data analytics. These will need to be addressed.

- Design the operations and technology architecture. Rather than develop IT features ad hoc manner as requirements emerge, managers need to establish capabilities-based IT principles. These will guide and govern IT architecture, its evolving design, and how features are built and operated. From a firm-wide perspective, companies must develop recommendations for a target-state technology solution that encompasses each IT capability. Here, selecting systems architecture becomes critical to ensure flexibility and meet evolving business needs. As part of creating durable, multi-user capabilities, IT managers must carefully design specs for the final application, determine how the data are going to be manipulated and decide what overarching infrastructure will accommodate it. For example, in most organizations, master customer data are scattered over diverse applications and databases. To support the financial institution's business requirements and to simplify the environment for the sales force - various customer systems will need to be integrated into one universal content-management system. This way, branches, and contact centers can access a real-time, 360-degree customer view from one readily accessible place. This not only pushes data to customer-facing employees when needed, but it also facilitates customer-focused service, segment-specific marketing, and sales analytics. On a daily basis, for example, such a platform could push customer feedback gathered from surveys directly to a call-center representative to follow up and resolve problems. When aggregated by the IT customer interface system to reflect the experiences of the hundreds of customers who required call-center service, the feedback can be used by supervisors and managers for front-line training or to elevate issues that may need higher-level attention. Finally, the platform would also enable market analysts to sort the feedback by customer segment in order to identify opportunities to improve service delivery to high-value targets or spot opportunities to cross-sell other products.

- Develop the IT Roadmap. Aligning IT with business objectives requires not only a capabilities-based goal but a roadmap to get there. To create one, managers must work together to identify key IT investment needs that will close the alignment gaps and then bundle them into IT investment themes. Following an acquisition, for example, a top priority will be to improve IT connectivity and efficiency across the merged companies. Thus, integrating the two organizations' systems ties into the business imperative to get a more granular view of all customers and how they rate the services they receive. Meanwhile, organizational capabilities needing an immediate upgrade might be consolidating finance, data warehouse, and human resources functions. Most leading firms sequence their IT investments. They develop a three- or five-year transformation roadmap for IT initiatives based on their strategic relevance, urgency, and ease of completion. They also build an investment plan based on the estimated cost to accomplish these IT initiatives and the return that investment is expected to yield.

- Reallocate IT spending as business priorities evolve. Periodically, companies need to reassess whether their technology investments remain aligned to business priorities by applying a business lens to IT costs. Sometimes it is necessary to refocus the project portfolio on the most critical capabilities, reallocate IT budgets accordingly and capture the savings. Frequent assessment of all projects against the IT strategy can identify significant amounts of unaligned IT costs early on that can be reallocated to new business priorities. For instance, IT capabilities may need to be revised as business needs change, creating opportunities to serve new customer segments. Other capabilities might begin to rise in priority, as well, such as the need to accommodate high-volume customer surveys, develop a capacity to mine verbatim feedback, and begin channeling the feedback to front-line employees.

Benefits of Capabilities-Driven IT[5]

With capabilities-driven IT, large financial institutions can begin to operate with the agility of fintech startups since technology is no longer a bottleneck but a fully integrated part of the business. Here are some of the benefits this approach will bring:

- Business needs met quickly and effectively. Since pods own both the technology and the talent needed to deliver each capability, and even non-technology specialists participate in IT development, collaboration is continuous. There is no more bureaucracy related to approvals or fights over priorities. Each capability pod decides how best to utilize its own resources to meet the business unit’s needs.

- More customer-centric products delivered faster. Because technology developers in the pods work closely with client-facing segments, they have greater insight into client feedback and can incorporate those insights into the development process. They can set and change priorities to meet evolving client expectations, develop products that are more tailored to customer needs, and get these products to market faster (and, if preferred, incrementally).

- Better engaged IT employees. Reducing intermediate steps between IT and business units does not just improve efficiency. It also makes employees more effective. Few things discourage technology personnel more than excessive bureaucracy. With less time spent on back-and-forths between different divisions, software developers can spend more time developing.

- More efficient capital allocation. No longer do business, and IT makes plans in isolation. Instead, capability pods define their technology needs, allowing management to better align investments to meet business objectives. Instead of monolithic technology investment processes, management allocates discretionary funds to capability pods in line with their needs and ability to generate incremental value.

- Better use of outsourcing and automation. Since the pods are no longer required to use the company’s centralized IT services, they can take advantage of software and infrastructure from external providers, and their combined business, operational, and technology skills enable them to assess with a business lens the trade-offs between third-party software’s functionality and costs. That assessment is often challenging in current models, where IT is separate from the business.

See Also

- IT Capability Maturity Framework (IT-CMF)

- IT Governance: Discussing the framework that ensures IT investments support business objectives through alignment and value delivery.

- Enterprise Architecture (EA): Exploring how organizations structure IT systems and processes to align with business goals.

- IT Infrastructure: Covering the composite hardware, software, network resources, and services required for the existence, operation, and management of an enterprise IT environment.

- IT Service Management (ITSM): Discussing the activities involved in designing, creating, delivering, supporting, and managing the lifecycle of IT services.

- Business IT Alignment: Exploring strategies that ensure the technology implementations and the business strategy and goals are in sync.

- Digital Transformation (DX): Discussing the integration of digital technology into all areas of a business, fundamentally changing how businesses operate and deliver value to customers.

- Technology Roadmapping: Exploring the planning technique for identifying, evaluating, and selecting strategic options for technology investments.

- Information Systems Strategy: Discussing how strategic management of information systems supports organizational strategies and objectives.

- Cloud Computing: Exploring how the use of cloud resources can enhance IT capabilities by providing scalable and efficient IT solutions.

- Cyber Security: Covering the strategies and techniques used to protect the IT environment and the data it contains from cyber threats, an essential component of IT capability.

References

Further Reading

- Understanding the link between Information Technology Capability and Organizational Agility: An Empirical Examination

- Cognizant Creating a Capability-Led IT Organization

- The Relationship between IT Flexibility, IT-Business Strategic Alignment, and IT Capability

- Building Information Technology Capabilities: A Case Study of the Development of an Integrated Management System