Roadmap

Definition of Roadmap[1]

A Roadmap is a strategic plan that defines a goal or desired outcome and includes the major steps or milestones needed to reach it. It also serves as a communication tool, a high-level document that helps articulate strategic thinking—the why—behind both the goal and the plan for getting there. When it comes to understanding the role of the roadmap, perhaps the most important concept to remember is that it is a strategic document, not a document that captures all of a plan’s details. With this in mind, it is also worth reviewing what it is not.

What a Roadmap Is Not

- It is not a backlog: This is another very specific type of document. A backlog is essentially a to-do list of the tasks required to complete a strategic initiative, ideally arranged according to priority. Roadmap planning is often the process of creating a high-level strategy out of a collection of backlog tasks and ideas. A roadmap, therefore, can and should work together with a backlog in the sense that the person responsible for the roadmap (typically a product manager in the case of a product roadmap) will translate its high-level strategic components into tasks that can be assigned and tracked throughout the project. Which leads to a related item that roadmaps are often confused with....

- It is not a project management tracker: Many managers confuse roadmaps with the documents or software applications used to compile all of the details to complete the initiative — the individual assignments, the personnel responsible for each task, meetings scheduled to discuss specific issues or milestones, deadlines for completing each element of the project, etc. These details should be tracked and updated throughout any strategic undertaking. But the tool for this will be a project management tracker, such as Trello, PivotalTracker or JIRA.

- It is not a list of features: Finally, many product managers mistakenly assume their planned list of features or epics constitutes the roadmap itself. But this is not the case.

Defining Goals for a Roadmap[2]

This step is arguably the most vital. After all, if you don’t set your targets right, it won’t matter how well you perform other steps – you will be heading in the wrong direction altogether. That’s why it’s crucial to grasp a couple important concepts when you start planning your own strategy.

- Vision: Vision is all about imagining your organization reaching its goals. Understand how this will affect it, what implications this might have, how the business environment will react, etc. Why is this so essential? Because you don’t want your aims to be set in vacuum, not bound to real problems and background. Envisioning your company having achieved its targets may help you come up with important related questions, like “what if we actually get there?” and “is this really what we need?”. Take heed – developing a Vision hides a certain pitfall. Seeing how it is usually a mental product of a business owner or a CEO, Vision can be subject to cognitive biases. This is a topic for another day, but for now – double make sure your goals pass the reality-check.

- Structural thinking: Many of us have heard about Pareto-efficiency – a principle that 20% of our efforts generates 80% of the results, and vice versa. Well, you could say that structural thinking is what you use to determine those most efficient 20% of efforts. This is how it works (don’t forget to set KPIs for each level!):

- choose your grand goal (for instance, earn X amount of $)

- derive subgoals that are integral to the success of the grand one (let’s say, sell Y amount of goods and reduce product cost by Z)

- derive sub-subgoals, and so on (the number of levels can vary depending on the size of the system; for SMBs 3-4 levels should be enough)

- use subgoals to define milestones for your roadmap (more on that later)

The pitfall of structural thinking is in how difficult it is for us humans to conduct proper induction. In general, you can’t be 100% sure that whatever subgoals you’ve derived are actually the crucial ones. That’s why it’s always recommended to double check them by performing a reverse operation to see if your trains of thought come back to the initial point.

- Black Swan theory: State of modern markets can be easily described by the VUCA concept. That is, they are Volatile, Uncertain, Complex, and Ambiguous. Any old-school long-term planning becomes nigh-impossible in such environment. It takes a business Vision, Understanding, Clarity, and Agility to have a chance to succeed on these markets. In this regard, no wonder why the Black Swan Theory by Nassim Nicholas Taleb becomes more and more popular nowadays. In this theory, a black swan is an event that has a major effect on business results, yet occurs unpredictably. What’s important is that you don’t have to try and forecast such events, but rather to build up the robustness of the business – being able to withstand the negatives while still exploiting the positives. Be sure to plan for big swans when deciding on your goals.

The Need for a Roadmap[3]

Successful product development and management requires that a product team manage the complexities of producing a series of products at the right costs, with the right features, and using the most appropriate technologies. Product-Technology Roadmapping leads a team to create a plan that integrates market and customer needs, product evolution, and introduction of new technologies at the beginning of their development journey. The roadmap makes sure that gaps in the plan are identified and can be closed as needed in the future. It also serves as a guide for the team during their journey, allowing them to recognize and act on events that require a change of direction. And roadmaps communicate the team’s plan to portfolio decision makers, to customers and to partners and suppliers.

- Roadmapping is just good planning, for all the areas that contribute to a successful product line. The roadmapping process leads a cross-functional planning team to fully examine potential competitive strategies and ways to implement those strategies. Technology decisions are made as an integral part of the plan, not just an afterthought.

- Roadmaps incorporate an explicit element of time. Roadmapping helps the team make sure that they will have the technologies and capabilities at the time they will be needed to carry out their strategy

- Roadmaps link business strategy and market data with product and technology decisions. Roadmapping prompts a team to be specific with respect to planned features or performance in terms of value for customers.

- Roadmaps reveal gaps in product and technology plans. Areas where plans are needed to achieve objectives become immediately apparent, and can be filled before they become problems.

- Roadmaps prioritize investments based on drivers. At every stage of the roadmapping process, the focus is on the few most important things: customer needs, product drivers or technology investments. The team is prompted to identify, implement, develop, or acquire the most important things first, spending time and resources in the best way. Also, with a set of roadmaps in a common format, portfolio decision makers are better equipped to make the tradeoffs and choices that meet the corporation’s objectives.

- Roadmapping helps set more competitive and realistic targets. Product performance targets are set in terms of the industry competitive landscape. For example, experience curves are an especially useful tool for establishing industry based targets. Recognizing that a winning product strategy usually cannot be all things to all people, the team sets objectives to lead, maintain parity, or lag competitors in specific areas.

- Roadmaps provide a guide to the team, allowing the team to recognize and act on events that require a change in direction. Part of the process of developing a roadmap is to create a risk roadmap, identifying those events or changes in conditions that signal a need to reevaluate and revisit the plan during the development journey.

- Sharing roadmaps allows strategic use of technology across product lines. Cross-roadmap reviews look across the plans of several product lines to find common needs, capabilities that can be leveraged, or development costs that can be shared. Roadmaps can also support a common corporate database of available or needed technologies.

- Roadmapping communicates business, technology and product plans to team members, management, customers, and suppliers. With a roadmap, a team can clearly explain to customers and suppliers where they are going. A roadmap gives customers information they can use in their own planning, and can be used to solicit their reaction and guidance. With suppliers, a roadmap is a framework for partnership and directions setting. The roadmap also tells the larger development team, corporate management, and other development teams where the product line is headed.

- Finally, roadmapping builds the development team. The roadmapping process builds a common understanding and shared ownership of the plan, incorporating ideas and insights from team members representing the many functions involved in a successful development process.

Types of Roadmaps[4]

Below are some common types of product roadmaps to help you figure out which one will work best for you. You should choose which of these views best supports the way you want to communicate and rally your organization around your product vision. The first three are examples focus on how to communicate the features you’re delivering, and the second two focus on communicating the timeline.

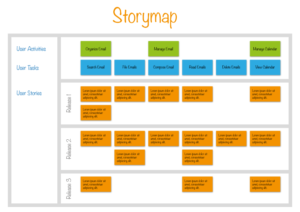

Story map

The story map is used in the beginning of new projects or products. It is an excellent way to create an overview of all the features which will be important to the product. Although the idea is not to create an unlimited list of all the features and functionalities that will likely be developed somewhere in the future, it does provide a starting point to facilitate creative ideas for the product. The story map is that it provides an overview of all the user activities that need to be covered by the system, which in turn enables you to create small and valuable user stories, which can be developed and delivered incrementally and iteratively. The story map starts with user activities, and thus taking a users' perspective on the product.

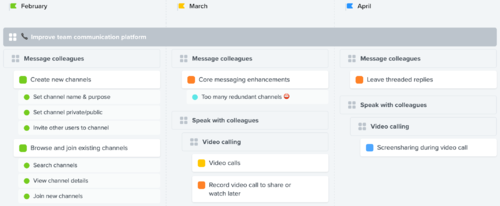

Feature-driven product roadmap

The most straightforward thing you can do is list out the features you plan on releasing. However, to provide more context for these features, you can show these features based on a hierarchy that shows your features in context with one another. The power of this level of information is that more people across your organization can easily understand it instead of looking at a laundry list of features. This view begins to tell a clear story about what you plan on delivering. Features are attributed to higher level themes, making it clear what those features will provide in the context of a broader plan. This level of structure lends itself easily to often used categorizations, including epics, stories, and tasks, which can be helpful if the biggest consumers of your roadmap are engineers and project managers.

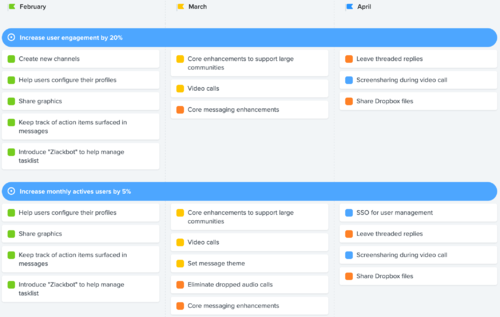

Objective-driven product roadmap

The key piece of information missing in the feature-based roadmap is the why. The objective-driven product roadmap ties your features to objectives, which makes it easy for anyone to understand why each feature is being developed. When using business-level objectives, this offers a clear connection between your product and business strategies. Someone might ask, “Why are we doing Feature X instead of Feature Y?” With other roadmaps, your answer may be tougher to answer. But with an objective-driven product roadmap, you can clearly show that Feature X directly ties to your company’s business objectives.

Time-based product roadmap

These next two roadmap views focus on the timeline. Time-based roadmaps focus on all of the features that will be coming in each product release in a general time frame. This can be helpful for teams, such as marketing, to organize activities around releases. Be wary about using tight time frames as this can set burdensome expectations. This is when roadmaps become more performative than useful, and you want to avoid this as it can lead to lower confidence in the product team. Consider using a time frame that works best to communicate your plans broadly. This may be monthly, quarterly, or any bucket of time you think works best for your needs. You also don’t need to maintain a consistent timeline to help organize features you plan on delivering in the long-term.

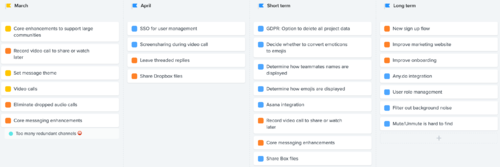

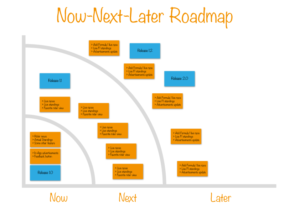

Now-Next-Later product roadmap

This view provides detailed near-term insight into what’s coming next. Typically, features in the ‘Now’ slot have more detail as they’re being worked on and features in the “Later’ bucket will likely be a bit more high level and can reflect your long-term strategy if you set it up correctly. This can be especially helpful in more engineering-focused organizations when the release cycles are generally understood. While this view is great for organizations that move quickly, you’ll want to make sure your prioritization process rigorously keeps things on track. What can happen is that things in Later stay in Later indefinitely while new ideas that are disconnected from the long term strategy make their way into the Now or Next buckets.

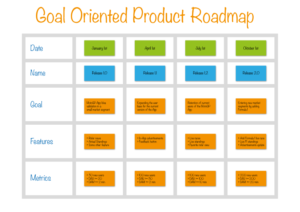

Goal Oriented product roadmap (GO product roadmap)

Unlike most product roadmaps, the GO roadmap is goal-oriented (hence the name). Goals such as user acquisition, activation or retention play a central role. This shifts the conversation from debating features to agreeing on strategic objectives, making smart investment decisions, and aligning the stakeholders. The GO product roadmap is designed for creating products with Lean Startup or Scrum. Use it to establish product goals, carry out release planning, and coordinate the development and launch of different products.

Collaborative Techniques to Build a Roadmap[5]

- The Radical Product prioritization — It is an exercise to relate features and potential outcomes to your product’s vision;

- The Go Product Roadmap by Roman Pichler — Doing this exercise, you and your team are going to list expected delivery dates, goals of each deliverable and metrics that are going to be used later on;

- The Lean Inception by Paulo Caroli — It is a five day exercise that is going to thoroughly make you and your team think about many aspects of the product, ending up with a MVP Canvas

The Advantages of Having a Roadmap[6]

Taking the roadmap from the start you can easily understand the advantages it provides:

- Having a vision statement should sum up what you actually want to achieve in one or two sentences. If you can’t do that then you should probably spend some time getting a clear picture of what you do actually want.

- The individual goals you need to achieve your vision are the main objectives you want to reach. This will add color and detail to the image you have of the success you are looking for.

- Each department and area of an organization will have a different view on what success is, by factoring these into your long-term roadmap you will have a more holistic picture of how things look from different angles.

- There are dozens of practices, formulas and ways of going about things in project management. Focusing your attention on what will be used and where physically saves time and mentally reduces stress from having to weigh things up for every action.

- The various tasks that need to be performed to make sure you reach your goals and realize your vision will be many and probably quite mundane but having them laid before you will make them visible and seem achievable.

- There are certain points along every journey where you can stop, take stock and be satisfied that everything is going according to plan. Laying out these milestones beforehand makes them easier to aim for and reach.

- There is no journey without danger of varying levels. In your case it will most likely be risks in the form of roadblocks, delays and missed targets which could derail you from your project path. The better idea you have of them, the more successful you will be at negotiating them.

See Also

- IT Roadmap

- Enterprise Architecture

- IT Governance

- Project Portfolio Management

- Stage-Gate

- IT Strategy

- Strategic Planning

- Strategic Planning Cycle

- Strategic Management

References

- ↑ Defining a Roadmap? ProductPlan

- ↑ How to define goals for a roadmap? Roadmap Planner

- ↑ Ten Reasons to Roadmap Albright Strategy

- ↑ Types of Roadmaps Productboard

- ↑ Collaborative Techniques to Build a Roadmap Product Coalition

- ↑ What are the Advantages of Having a Roadmap Clarizen