Human Computer Interaction (HCI)

Human Computer Interaction (HCI) is what happens when a human user and a computer system, in the broadest sense, get together to accomplish something. Human–computer interaction is a multidisciplinary practice that centers on the interaction between humans (users) and the computer including design of the computer interface. At first, HCI was primarily focused on computers, but with the advent of the personal computer it has expanded to include almost all variations of information technology design.

The Rise of Human Computer Interaction (HCI)[1]

HCI surfaced in the 1980s with the advent of personal computing, just as machines such as the Apple Macintosh, IBM PC 5150 and Commodore 64 started turning up in homes and offices in society-changing numbers. For the first time, sophisticated electronic systems were available to general consumers for uses such as word processors, games units and accounting aids. Consequently, as computers were no longer room-sized, expensive tools exclusively built for experts in specialized environments, the need to create human-computer interaction that was also easy and efficient for less experienced users became increasingly vital. From its origins, HCI would expand to incorporate multiple disciplines, such as computer science, cognitive science and human-factors engineering.

HCI soon became the subject of intense academic investigation. Those who studied and worked in HCI saw it as a crucial instrument to popularize the idea that the interaction between a computer and the user should resemble a human-to-human, open-ended dialogue. Initially, HCI researchers focused on improving the usability of desktop computers (i.e., practitioners concentrated on how easy computers are to learn and use). However, with the rise of technologies such as the Internet and the smartphone, computer use would increasingly move away from the desktop to embrace the mobile world. Also, HCI has steadily encompassed more fields.

Human Computer Interactions in MIS[2]

From the MIS perspective, HCI studies examine how humans interact with information, technologies, and tasks, especially in business, managerial, organizational, and cultural contexts (Zhang et al., 2002). This differs notably from HCI studies in disciplines such as computer science, psychology, and ergonomics. MIS researchers emphasize managerial and organizational contexts by analyzing tasks and outcomes at a level relevant to organizational effectiveness. The features that distinguish MIS from other “homes” of HCI are its business application and management orientation (Zhang et al., 2004).

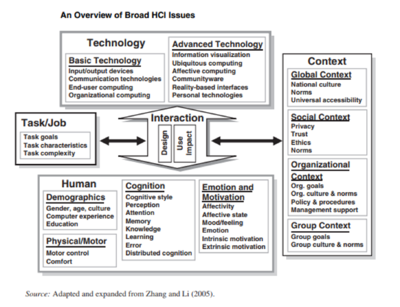

Over many years, the MIS discipline has gone through the process of clarifying its boundary. The same process has been occurring in the HCI sub-discipline (Zhang and Li, 2005). Based on the definition of HCI research in MIS given above (Zhang et al., 2002), the figure below represents a broad view of important HCI components that are pertinent to human interaction with technologies. Five components are identified: human and technology as the basic components, interaction as the core of interest, and task and context as the components making HCI issues meaningful. Several topics are listed inside each component to illustrate the components and the relationships among them. The two basic components encompass human and technology. There can be many different ways of understanding humans in general and their specific characteristics pertinent to their interaction with IT. The figure includes four categories: (1) demographics; (2) physical or motor skills; (3) cognitive issues; and (4) affective and motivational aspects. Personalities or traits can be examined within both the cognitive and affective categories. Many issues in the Human component fall into the ergonomics and psychology disciplines. HCI focuses, though, on the interplay between the human component and other components. Technology can be broadly defined to include hardware, software, applications, data, information, knowledge, services, and procedures. The figure indicates one way of examining technological issues when studying HCI. Many of these technological issues have interested researchers in the HCI field for a long time (Shneiderman, 1987; Shneiderman and Plaisant, 2005). The figure was developed from the perspective of technology types often found in technical fields such as computer science or studies associated with the computer-human interaction (CHI) community.

The Interaction between Human and Technology represents the “I” in HCI. It is the core or the center of all the action in HCI studies. Interaction issues have been studied from two aspects of the IT artifact life cycle: during the IT development stage (before release), and during its use and impact stage (after release). Traditionally, HCI studies, especially research captured by ACM SIGCHI conferences and journals, were concerned with designing and implementing interactive systems for specified users, including usability issues. The primary focus has been the issues prior to the technology’s release and actual use. Ideally, concerns and understanding from both points of view—human and technological—should influence design and usability issues.

The “Use/Impact” box on the right side inside the Interaction in the figure is concerned with actual IT use in real contexts and its impact on users, organizations, and societies. Design studies can be and should be informed by what we learn from the use of the same or similar technologies. Thus, use/impact studies have implications for future designs. Historically, use/impact studies have been the focal concern of MIS, along with human factors and ergonomics, organizational psychology, social psychology, and other social science disciplines. In the MIS discipline, studies of individual reactions to technology (e.g., Compeau et al., 1999), IS evaluation from both individual and organizational levels (e.g., Goodhue, 1997; Goodhue, 1998; Goodhue, 1995; Goodhue and Thompson, 1995), and user technology acceptance (e.g., Davis, 1989; Venkatesh and Davis, 2000; Venkatesh et al., 2003) all fall into this area.

Humans use technologies not for the sake of those technologies, but to support tasks that are relevant or meaningful to their jobs or personal goals. In addition, people carry out tasks in settings or contexts that impose constraints on doing and completing the tasks. Four contexts are identified: group, organizational, social, and global. The Task and Context boxes add dynamic and essential meanings to the interaction experience. In this sense, studies of human-computer interaction are moderated by tasks and contexts. It is these broader task and context considerations that separate the primary foci of HCI studies in MIS from HCI studies in other disciplines. Later, we will discuss more disciplinary differences.

The Goals of HCI[3]

The goals of HCI are to produce usable and safe systems, as well as functional systems. In order o produce computer systems with good usability, developers must attempt to:

- understand the factors that determine how people use technology

- develop tools and techniques to enable building suitable systems

- achieve efficient, effective, and safe interaction

- put people first

Underlying the whole theme of HCI is the belief that people using a computer system should come first. Their needs, capabilities and preferences for conducting various tasks should direct developers in the way that they design systems. People should not have to change the way that they use a system in order to fit in with it. Instead, the system should be designed to match their requirements.

Applications of HCI[4]

Human-computer researchers are assets to a number of organizations that develop mission-critical software, Edmunds says. The Federal Aviation Administration, for example, employs an HCI division that studies control towers. Before making changes to the color or the font used in the air traffic control software, they perform rigorous studies to understand how the changes might affect the users. Otherwise, Edmunds says, software changes without the proper research and testing could be disastrous. While other organizations may not dedicate an entire division to HCI, the principles derived from it are applicable to a number of jobs. For example:

- Product developers may use HCI methodologies to better understand the user of a new electronic device or software the company is planning to launch.

- User experience developers may employ HCI research to make sure the company’s website or advertisements encourage customers to buy.

- Data scientists may study HCI to develop data visualization dashboards that best convey information in the most usable way.

- Software engineers may employ HCI research when developing revolutionary products for new audiences.

HCI Best practices[5]

- Make elements in your interface legible: If the characters or objects being displayed cannot be perceptible, they cannot be used effectively.

- Redundancy is important: If a signal is presented more than once, it is more likely that it will be understood correctly. Redundancy does not imply repetition. A traffic light is a good example of redundancy, as color and position are redundant.

- Similarity confuses: Use distinguishable elements. Signals that appear to be similar will likely be confused. Unnecessarily similar features should be removed and dissimilar features should be highlighted.

- Use multiple resources: A user can more easily process information across different resources. For example, visual and auditory information can be presented simultaneously rather than presenting all visual or all auditory information.

- Replace memory with visual information: A user should not need to retain important information solely in working memory or retrieve it from long-term memory. A menu, checklist, or another display can aid the user by easing the use of their memory.

- Don’t reinvent the wheel: Old habits from other interfaces will easily transfer to support the processing of new ones if they are designed consistently. A design must accept this fact and use the standards already used in similar interfaces.

See Also

- Artificial General Intelligence (AGI)

- Artificial Neural Network (ANN)

- Human-Centered Design (HCD)

- Machine-to-Machine (M2M)

- Machine Learning

- Predictive Analytics

- Data Analytics

- Data Analysis

- Big Data

- Cognitive Computing

References

- ↑ The Meteoric Rise of HCI Interaction-Design

- ↑ Human Computer Interactions in MIS Zhang and Galletta

- ↑ What are the The Goals of HCI? University of Birmingham

- ↑ What are some Applications of Human-Computer Interaction? Northeastern University

- ↑ Some Best Practices in Designing Human friendly Computer Interfaces Exaud