Project Governance

What is Project Governance?

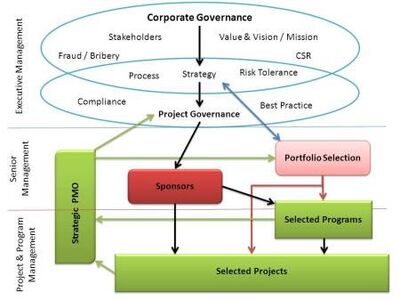

Project Governance is a sub-set of corporate governance, focused on systems that ensure the right projects and programs are selected by the organization, and the selected ‘few’ are accomplished as efficiently as possible. Projects that no longer contribute value to an organization should be terminated in a way that conserves the maximum value and the resources reallocated through the portfolio management process to more valuable endeavors.

source: Stakeholder Management

Project Governance refers to “the framework, functions, and processes that guide project management” (according to A Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge – Sixth Edition). This oversight function is aligned with the organization’s leadership structure and decision-making processes. The governance encompasses the entire project life cycle and defines structured roles, responsibilities and accountabilities within the project. The benefits include effective oversight and improved control, integration, and decision making. While there is no one framework that is effective in all organizations, it is recommended that the model includes the following components:

- Definitive leadership accountabilities and responsibilities

- Alignment and stakeholder engagement

- Risk and issue management

- Assurance: monitoring and controlling processes[1]

The Three Pillars of Project Governance[2]

Project governance essentially describes three things:

- Structure: The organization’s structure and environment have to support the project. That means senior management is willing to invest time and energy to establish a vision for project managers to take forward. The “structure” element of project governance describes not just the immediate project team, but the company as a whole.

- People: Investing in effective project managers is key to any project. But first, senior management needs to understand their current activities. From this, project governance can establish the goals each PM should achieve. These goals need to be clear, reachable and sustainable.

- Information: While it’s important to understand people, the process is even more important. Regardless of how many goals are set or what the vision is, every project will suffer without clear and consistent information sharing.

Project Governance Components[3]

According to PMI, eight project governance components add value to the real world:

- Governance Models: Based on the project’s scope, timeline, complexity, risk, stakeholders, and importance to the organization, the organization should formulate a baseline of critical elements needed for project governance. There should be a primary tool that based on some of the above indicators decides what changes your governance framework needs to have and which components are compulsory.

- Accountability and Responsibilities: Defining accountability and responsibilities is the core of the project manager’s tasks. Improper distribution of accountability and responsibilities will have a negative impact on the effectiveness of operations of an organization. While defining both the factors, the project manager not only needs to define who is accountable, but also who is responsible, consulted, and notified for each of the project’s deliverables.

- Stakeholder Engagement: While laying down the foundation of your governance plan, it is compulsory to understand the project ecosystem completely. Identifying all the stakeholders is the first step. If even one stakeholder is left out, it can disrupt the entire project and can have an adverse effect. You need to identify the stakeholders from a wide spectrum of sponsors, suppliers, the project team, government boards, business owners, and so on. The project manager has to define who the stakeholders are, what their interests and prospects are, and most importantly, how to communicate with them.

source: Project Management Institute

- Stakeholder Communication: Once all the stakeholders have been recognized and their interests and expectations have been described, the project manager needs to develop a communication plan. A well-devised communication plan delivers concise, efficient, and well-timed information to all stakeholders.

- Meeting and Reporting: Once the communication plan is appropriately defined, the project manager ensures that the balance of meetings and reporting is right. It is essential to define the communication plan to ensure that each stakeholder understands the mode and content of the communication, owner, receiver, communication milestones, and decision gates. In addition, communication needs to be brief, precise, and to the point.

- Risk and Issue Management: Due to uncertainties and unpredictability associated with projects or programs, they are loaded with risks and issues. It is tough to predict what is going to happen, but it is necessary as a lack of preparation will put the project team much further behind. At the initiation of any project or program, there needs to be an agreement on how to identify, categorize, and prioritize the risks and issues. The tact of handling the risk or issue is more important than the issue itself.

- Assurance: Project assurance sees that risks and issues are managed efficiently and outlines the metrics that bring the delivery confidence of the project. One of the most essential components of assurance is creating the metrics that would give a view of the project performance.

Core Project Governance Principles[4]

Project governance frameworks should be based around a number of core principles in order to ensure their effectiveness.

- Principle 1: Ensure a single point of accountability for the success of the project: The most fundamental project accountability is accountability for the success of the project. A project without a clear understanding of who assumes accountability for its success has no clear leadership. With no clear accountability for project success, there is no one person driving the solution of the difficult issues that beset all projects at some point in their life. It also slows the project during the crucial project initiation phase since there is no one person to take the important decisions necessary to place the project on a firm footing. The concept of a single point of accountability is the first principle of effective project governance. However, it is not enough to nominate someone to be accountable – the right person must be made accountable. There are two aspects to this. The accountable person must hold sufficient authority within the organization to ensure they are empowered to make the decisions necessary for the project’s success. Beyond this however is the fact that the right person from the correct area within the organization be held accountable. If the wrong person is selected, the project is no better placed than if no one was accountable for its success. The single person who will assume accountability for the success of the project is the subject of Principle 2.

- Principle 2: Project ownership independent of Asset ownership, Service ownership or other stakeholder group: Often organizations promote the allocation of the Project Owner role to the service owner or asset owner with the goal of providing more certainty that the project will meet these owner's fundamental needs, which is also a critical project success measure. However, the result of this approach can involve wasteful scope inclusions and failure to achieve alternative stakeholder and customer requirements:

- The benefit of the doubt goes to the stakeholder allocated with the Project Owner responsibility, skewing the project outcome;

- Project Owner requirements receive less scrutiny, reducing innovation and reducing outcome efficiency;

- Different skill sets surround Project ownership, Asset ownership and Service ownership placing sound project decision making and procedure at risk;

- Operational needs always prevail, placing the project at risk of being neglected during such times;

- Project contingencies are at risk of being allocated to additional scope for the stakeholder allocated project ownership.

The only proven mechanism for ensuring projects meet customer and stakeholder needs, while optimizing value for money, is to allocate Project ownership to specialist party, that otherwise would not be a stakeholder to the project. This is principle No. 2 of project governance. The Project Owner is engaged under clear terms which outline the organizations key result areas and the organization's view of the key project stakeholders. Often, organizations establish a Governance of Projects Committee, which identifies the existence of projects and appoints project owners as early as possible in a project's life, establishes Project Councils which form the basis of customer and stakeholder engagement, establishes the key result areas for a project consistent with the organizations values, and, oversees the performance of projects. These parameters are commonly detailed in a Project Governance Plan which remains in place for the life of the project (and is distinct from a Project Management Plan which is more detailed and only comes into existence during the development of the project). Projects have many stakeholders and an effective project governance framework must address their needs. The next principle deals with the manner in which this should occur.

- Principle 3: Ensure separation of stakeholder management and project decision making activities: The decision making effectiveness of a committee can be thought of as being inversely proportional to its size. Not only can large committees fail to make timely decisions, those it does make are often ill-considered because of the particular group dynamics at play. As project decision making forums grow in size, they tend to morph into stakeholder management groups. When numbers increase, the detailed understanding of each attendee of the critical project issues reduces. Many of those present attend not to make decisions but as a way of finding out what is happening on the project. Not only is there insufficient time for each person to make their point, but those with the most valid input must compete for time and influence with those with only a peripheral involvement in the project. Further not all present will have the same level of understanding of the issues and so time is wasted bringing everyone up to speed on the particular issues being discussed. Hence, to all intents and purposes, large project committees are constituted more as a stakeholder management forum than a project decision making forum. This is a major issue when the project is depending upon the committee to make timely decisions. There is no question that both activities, project decision making and stakeholder management, are essential to the success of the project. The issue is that they are two separate activities and need to be treated as such. This is the third principle of effective project governance. If this separation can be achieved, it will avoid clogging the decision making forum with numerous stakeholders by constraining its membership to only those select stakeholders absolutely central to its success. There is always the concern that this solution will lead to a further problem if disgruntled stakeholders do not consider their needs are being met. Whatever stakeholder management mechanism that is put in place must adequately address the needs of all project stakeholders. It will need to capture their input and views and address their concerns to their satisfaction. This can be achieved in part by chairing of any key stakeholder groups by the chair of the Project Board. This ensures that stakeholders have the project owner (or SRO) to champion their issues and concerns within the Project Board.

- Principle 4: Ensure separation of project governance and organizational governance structures: Project governance structures are established precisely because it is recognized that organization structures do not provide the necessary framework to deliver a project. Projects require flexibility and speed of decision making and the hierarchical mechanisms associated with organization charts do not enable this. Project governance structures overcome this by drawing the key decision makers out of the organization structure and placing them in a forum thereby avoiding the serial decision making process associated with hierarchies. Consequently, the project governance framework established for a project should remain separate from the organization structure. It is recognized that the organization has valid requirements in terms of reporting and stakeholder involvement. However dedicated reporting mechanisms established by the project can address the former and the project governance framework must itself address the latter. What should be avoided is the situation where the decisions of the steering committee or project board are required to be ratified by one or more persons in the organization outside of that project decision making forum; either include these individuals as members of the project decision making body or fully empower the current steering committee/project board. The steering committee/project board is responsible for approving, reviewing progress, and delivering the project outcomes, and its intended benefits, therefore, they must have capacity to make decisions, which may commit resources and funding outside the original plan. This is the final principle of effective project governance. Adoption of this principle will minimize multi layered decision making and the time delays and inefficiencies associated with it. It will ensure a project decision making body empowered to make decisions in a timely manner.

Additional and Complementary Principles of Governance

The board has overall responsibility for governance of project management. The roles, responsibilities and performance criteria for the governance of project management are clearly defined. Disciplined governance arrangements, supported by appropriate methods and controls are applied throughout the project life cycle. A coherent and supportive relationship is demonstrated between the overall business strategy and the project portfolio. All projects have an approved plan containing authorization points, at which the business case is reviewed and approved. Decisions made at authorization points are recorded and communicated. Members of delegated authorization bodies have sufficient representation, competence, authority and resources to enable them to make appropriate decisions. The project business case is supported by relevant and realistic information that provides a reliable basis for making authorization decisions. The board or its delegated agents decide when independent scrutiny of projects and project management systems is required, and implement such scrutiny accordingly.

There are clearly defined criteria for reporting project status and for the escalation of risks and issues to the levels required by the organization. The organization fosters a culture of improvement and of frank internal disclosure of project information. Project stakeholders are engaged at a level that is commensurate with their importance to the organization and in a manner that fosters trust.

Principles for Multi-owned Projects

Multi-owned is defined as being a project where the board shares ultimate control with other parties. The principles are:

- There should be formally agreed governance arrangements

- There should be a single point of decision making for the project

- There should be a clear and unambiguous allocation of authority for representing the project in contacts with owners, stakeholders and third parties

- The project business case should include agreed, and current, definitions of project objectives, the role of each owner, their incentives, inputs, authority and responsibility

- Each owner should assure itself that the legal competence and obligations and internal governance arrangements of co-owners, are compatible with its acceptable standards of governance for the project

- There should be project authorization points and limiting constraints to give owners the necessary degree of control over the project

- There should be agreed recognition and allocation or sharing of rewards and risks taking into account ability to influence the outcome and creating incentives to foster co-operative behavior

- Project leadership should exploit synergies arising from multi-ownership and should actively manage potential sources of conflict or inefficiency

- There should be a formal agreement that defines the process to be invoked and the consequences for assets and owners when a material change of ownership is considered

- Reporting during both the project and the realization of benefits should provide honest, timely, realistic and relevant data on progress, achievements, forecasts and risks to the extent required for good *governance by owners

- There should be a mechanism in place to invoke independent review or scrutiny when it is in the legitimate interests of one or more of the project owners.

- There should be a dispute resolution process agreed between owners that does not endanger the achievement of project objectives.

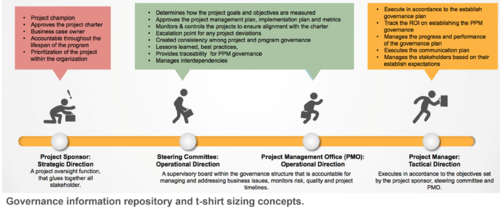

Project Governance Roles[5]

All projects and programs have different characteristics and mandates. They encapsulate many roles but there are four main roles that are required to establish, maintain and enforce project governance. Each of theses roles views the project through a different lens. The four crucial roles that are needed to establish, direct, implement and validate project governance are the following:

- Project Sponsor

- Steering Committee

- Project Management Office

- Project Manager.

The figure below depicts the key roles and responsibilities and how each role influences the Governance Framework:

source: Project Management Institute

Choosing a Project Governance Model[6]

There is no ‘perfect’ governance model as the right approach for you will depend on your organization, the maturity of the team and the culture of project delivery. The trick is to land on a model that offers just the right amount of structure and support while avoiding the perception of bureaucracy.

When considering what project governance model to create or implement for your organization, here are some factors to take into account:

- Project Characteristics: A large project with a multi-billion dollar spend is going to have different monitoring and control requirements to a small project being managed within a single department. The governance model you adopt needs to fit the kinds of projects that you do. It’s OK to have several models if that makes sense for your business. For example, you could have one set of governance principles that apply to your highly strategic projects, and another for smaller initiatives. Or you could have a model that works for highly risky projects and another that’s used for low risk initiatives.

- Project Roles: Think about how the power structures in the organization work. A ‘standard’ approach for governance is to have a project sponsor as the ultimate decision-making authority, supported by a project board or steering group that provides challenge, direction and oversight. However, if you work in a social enterprise, a public benefit corporation or a firm that works on the principles of sociocracy, you may have a wider group of consultative and decision-making roles. Think about the roles that you would need to involve in making sure projects are being carried out in a responsible way. Roles are normally documented in a roles and responsibilities document which can also include the structure or hierarchy for the project team.

- Processes: Consider what processes you need and how they are going to apply to different kinds of projects. Here are some typical processes that support governance:

- Approval for project to begin

- Change control process for introducing changes to the project

- Approval to proceed at specific milestones or at the end of project phases

- Approval process for receipt and sign off on the final deliverables.

Normally, any project process that needs authorization from someone would be considered a governance process – even if it’s the project manager doing the authorizing.

- Documentation: Some PMOs mandate a list of the minimum documentation requirements for a project. Project managers can, of course, create more documents as necessary to keep the project moving forward, but the mandated documents must exist for every project. Some examples that could fall into your mandatory list include:

- Business case

- Project Charter

- Project plan

- Project closure document.

Project Governance vs. Corporate Governance vs. Project Management[7]

Project and corporate governance are related, but they aren’t the same thing. Corporate governance works on a much larger scale by informing suppliers, local government, consumers and anyone else that may have an impact on the entire company. They work to ensure that all internal projects have room to grow. The scale of information they receive has to be condensed for the team.

Think of corporate governance as being a whole while project governance is made up of many parts. Corporate is the tree while the projects are the leaves, so to speak. Project governance speaks to the company, which in turn talks to everyone else. Many people are involved with a single project, and they may be unaware that they have any impact at all. While this can put pressure on a project team, it also allows for more information to come in and better decisions to be made.

In terms of project management, this is also not the same as project governance. The difference is on focus and intent.

Governance is focused on creating the environment for good project management, ensuring the organization’s management is good. Project governance is performed at the top end of the corporation or business, while project management is focused on delivering results for the governing body. However, successful project governance is important for successful project management, and vice versa.

Benefits of Project Governance[8]

The key benefits of good project governance are described beleow:

- The right projects are approved: Every organization has limited resources, money and people. It is imperative that this resource is focused on those projects that contribute best to corporate goals, delivering the highest return on investment. A formal approval process ensures each project idea is evaluated in the cold light of day, by suitably authorized people, against competing priorities (& other project ideas) with only the best moving forward into detail planning. Managers should not busy themselves with pet projects at the expense of the wider organization.

- Better scope management: The number one reason why projects fail to deliver defined benefits on time, cost & quality is scope creep or lack of scope definition. Documenting and approving the agreed scope is critical to any organization looking to achieve some sort of project management maturity. This is usually a scoping document, perhaps a PID (PRINCE2 term) or PMP (APM term), or whatever you want to label it. Good governance ensures project managers, sponsors and project teams follow an agreed approach. This agreed approach includes completing appropriate project documentation and top of that list (ok, maybe second after a Business Case) is the scoping document. Good governance ensures the appropriate people review and sign off the proposed project scope. For a local or departmental project, this could be the assigned project sponsor. For large corporate investments, this could be the Portfolio Board or several senior executives. Without a scoping document we are likely to fail, without *Better change control: The organization is not static. Project scope & goals are also not static. Senior people do tend to change their minds. There are many reasons why we might need to change something on an approved project. We might look to add scope, request more funding, or move to a revised deadline. These significant changes should not fall to the project manager. Rather, the project manager should ensure an appropriate change control process is followed enabling decisions at the appropriate level. If a task is going to be delayed by 5 days, then maybe the project team manages this themselves. If the go-live date is going to shift by 2 months then its probably something for review at Portfolio Board as part of good governance. The project team should capture and evaluate any requests for change. Those with significant impact (as defined by the governance process) should then be escalated to the appropriate decision-maker(s). Perhaps the sponsor is the appropriate approved, or rejecter of the change, or perhaps it needs to be escalated further. Good governance provides a clear change control decision-making process.

- Stage Gates: We’ve planned the project, now let’s crack on. We’ve completed the work, now let’s close the project. Project teams may look to move through project stages (planning, implementation, closure) with little regard for the process, after all, they just want to get to the end as quickly as possible to claim victory. Stage gates ensure projects are reviewed formally at key points through the project journey. They ensure project teams have completed the agreed defined processes to the right standard and are correctly prepared for the next phase. On approval, the project team is allowed through the gate into the next stage. The number of stage gates and the rigor of the approval process should reflect the scale, complexity, risk and cost of each project. Good governance ensures projects and project teams can demonstrate they have completed each stage correctly and are ready to progress to the next.

- Clarity of roles and responsibilities: Governance provides the framework for projects. Good governance includes clear guidance on the role of the project team, project manager, sponsor and decision-making entities such as Portfolio Board. Good governance ensures we have a clear common understanding of roles and level of responsibility. This provides the foundation for clear escalation of risks and issues as well as proposed changes. Clarity of who does what and the agreed approach to selecting, planning, running and closing projects is fundamental to project success in the long term. This can only happen if there is a clear governance framework. This framework needs to be fit for purpose, not fit to burst with bureaucracy. If the right information is presented at the right time, then decision making can not only be quick, but it can also be well informed. Good governance is the key.

Challenges in Project Governance[9]

- Decision making: Decision making can be the most challenging aspect in IT projects. Most people often do not want to make decisions. Slow decision

making has severe impact on most IT projects in the organization. “Lack of decision making creates frustration in project teams as they felt there with no sense of leadership or direction.

- Risk management: The lack of risk management strategies within projects also poses major challenge. When strategies for managing risks are not in place for IT projects it affects the quality of products delivered to customers.

- Communication: Lack of initiative to communicate is a contributing factor to the challenges with communication. It affects both the team and the customer and as such damages the reputation of the organization.

- Roles, Responsibilities and Accountability: Undefined roles, responsibilities and accountability pose a challenge with project governance processes. This results in conflict amongst project members. Lack of accountability is also a result of lack of leadership and self management which in turn affects project deliverables.

See Also

- IT Governance

- IT Governance Framework

- Governance, Risk And Compliance (GRC)

- Government Enterprise Architecture (GEA)

- Government Interoperability Maturity Matrix (GIMM)

References

- ↑ Definition - What Does Project Governance Mean? JLL

- ↑ What are the three pillars of project governance? Project Management Qualification

- ↑ Project Governance Components Invensis

- ↑ Core project governance principles Wikipedia

- ↑ Roles That Are a Necessity for Establishing and Maintaining Project/Program Governance PMI

- ↑ Considerations for Project Governance Models Tensix

- ↑ Project Governance vs. Corporate Governance vs. Project Management Project-Management

- ↑ 5 Benefits of Good Project Governance Wellingtone

- ↑ Challenges of Project Governance Processes of IT Projects Refiloe Mashiloane, Osden Jokonya