Organizational Structure

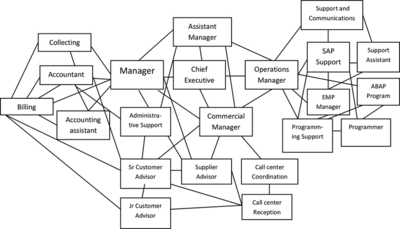

Organizational Structure is a system used to define a hierarchy within an organization. It identifies each job, its function and where it reports to within the organization. This structure is developed to establish how an organization operates and assists an organization in obtaining its goals to allow for future growth. The structure is illustrated using an organizational chart.[1]

Centralized vs. Decentralized Organizational Structures[2]

An organizational structure is either centralized or decentralized. Traditionally, organizations have been structured with centralized leadership and a defined chain of command. The military is an organization famous for its highly centralized structure, with a long and specific hierarchy of superiors and subordinates. In a centralized organizational system, there are very clear responsibilities for each role, with subordinate roles defaulting to the guidance of their superiors.

There has been a rise in decentralized organizations, as is the case with many technology startups. This allows companies to remain fast, agile, and adaptable, with almost every employee receiving a high level of personal agency. For example, Johnson & Johnson is a company that's known for its decentralized structure. As a large company with over 200 business units and brands that function in sometimes very different industries, each operates autonomously. Even in decentralized companies, there are still usually built-in hierarchies (such as the chief operating officer operating at a higher level than an entry-level associate). However, teams are empowered to make their own decisions and come to the best conclusion without necessarily getting "approval" from up top.

Types of Organizational Structures[3]

- Hierarchical Structure: A hierarchical structure, also known as a line organization, is the most common type of organizational structure. Its chain of command is the one that likely comes to mind when you think of any company: Power flows from the board of directors down to the CEO through the rest of the company from top to bottom. This makes the hierarchical structure a centralized organizational structure. In a hierarchical structure, a staff director often supervises all departments and reports to the CEO. There are two types of Hierarchical Structures:

- Functional Structure: The functional structure is a centralized structure that greatly overlaps with the hierarchical structure. However, the role of a staff director instead falls to each department head – in other words, each department has its own staff director, who reports to the CEO.

- Divisional Structure: The centralized structure, known as a divisional organization, is more common in enterprise companies with many large departments, markets or territories. For example, a food conglomerate may operate on a divisional structure so that each of its food lines and products can have full autonomy. In the divisional structure, each line or product has its own chief commanding executive.

source: The Org

- Flat Structure: A flat structure is a decentralized organizational structure in which almost all employees have equal power. At most, executives may have just a bit more authority than employees, as seen in the figure below. This organizational structure is common in startups that take a modern approach to work or don't yet have enough employees to divide into departments.

source: The Org

Matrix Structure: The matrix structure is a fluid form of the classic hierarchical structure. This centralized organization structure allows employees to move from one department to another as needed, as the horizontal lines in this matrix organization figure below indicates.

source: The Org

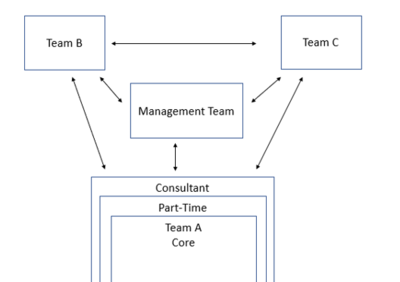

- Team Structure: A team structure is a decentralized but formal structure that allows department heads to collaborate with employees from other departments as needed. It is similar to a matrix structure; although, the focus is less on employee fluidity than on supervisor fluidity, leading to a decentralized functional structure.

- Network Structure: A network structure is especially suitable for a large, multi-city or even international company operating in the modern era. It organizes not just the relationships among departments in one office location, but the relationships among different locations and each location's team of freelancers, third-party companies to whom certain tasks are outsourced, and more. While this may sound like a lot for one type of network structure to detail

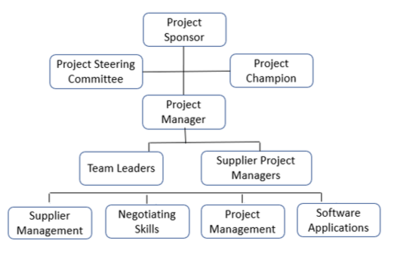

- Projectized Structure: In a projectized structure, the focus is on one project at a time. In this centralized organizational structure, project managers act as supervisors, not just resource allocators and decision-makers. Unlike other structure types, a projectized structure involves the demobilization of teams and resources upon a project's completion. But it's like other types of organizational structures in that an obvious hierarchy exists

Elements of Organizational Structure[4]

A strategic, carefully planned organizational structure helps a business run effectively and efficiently. An ineffective structure can cause significant problems for a company, including lost profits, rapid employee turnover and loss in productivity. Management experts use the six basic elements of organizational structure to devise the right plan for a specific company. These elements are: departmentalization, chain of command, span of control, centralization or decentralization, work specialization and the degree of formalization. Each of these elements affects how workers engage with each other, management and their jobs in order to achieve the employer’s goals.

- Departmentalization: Departmentalization refers to how the organizational structure groups the company's functions, offices and teams. Those individual groups are typically referred to as departments. Departments are usually sorted on the basis of the kinds of tasks the workers in each department perform, but this is not the only way to create a company’s departmental breakdown. You could also divide the business into groups based on product or brand lines, geographic locations or even customer needs.

- Chain of Command: Most organizations, from businesses to nonprofits to the military, utilize a chain of command. This helps eliminate inefficiencies by having each employee report to a single manager, instead of to several bosses. In the corporate context, this type of chain of command is reflected in the organizational structure and affects job descriptions as well as office hierarchies. Managers assign tasks, communicate expectations and deadlines to employees, and provide motivation on a one-to-many basis. When employees encounter obstacles or problems, they report back to the appropriate manager. When necessary, the manager is then responsible for taking the concern or issue up the chain of command to the next level, and so forth. This chain of authority or command streamlines corporate operations and communications for a more efficient and productive business.

- Span of Control: An organization’s span of control defines how many employees each manager is responsible for within the company. There is no single type of span of control that’s ideal for all companies or even for all businesses in a specific industry. The optimal span will depend on a number of factors, including the size of the workforce, how the company is divided into departments and even the company’s specific business goals and strategies. Other factors to consider are the type of manager assigned to each specific department and the job descriptions of the employees reporting to that manager. Based on the manager’s individual style or approach, the span of control could range from three or four to 15 or more. Of course, managers who are placed higher up the chain of command typically have a tighter span of control, as they are directly responsible for middle-manager or team leaders.

- Centralization and Decentralization: Organizational structures also rest somewhere on a spectrum of centralization. Generally, more conservative corporate entities adopt a centralized structure. In this design, C-level managers make all the decisions, management designs a plan for execution and front-line employees carry out that plan. C-level officers are generally those at the uppermost level of the organizational chart, such as the chief executive officer, chief operating officer and chief marketing officer. Centralizing authority in a business means that middle management typically is left with little to no input about the goals the company sets. This system is typical in larger corporate organizations, as well as at companies in more conservative industries. On the other hand, a company could adopt a more decentralized approach. A decentralized system allows all levels of management the opportunity to give input on big-vision goals and objectives. Larger, company-wide decisions are still generally reserved to C-level officers, but departmental managers enjoy a greater degree of latitude in how their teams operate.

- Work Specialization: In any business, employees at all levels typically are given a description of their duties and the expectations that come with their positions. In larger companies, job descriptions are generally formally adopted in writing. This approach helps ensure that the company’s specific workforce needs are met, without any unnecessary duplication of effort. Work specialization ensures that all employees have specific duties that they are expected to perform based on each employee's work experience, education and skills. This prevents an expectation that employees will perform tasks for which they have no previous experience or training and to keep them from performing beneath their capacities.

- Formalization: Finally, organizational structures implement some degree of formalization. This element outlines inter-organizational relationships. Formalization is the element that determines the company’s procedures, rules and guidelines as adopted by management. Formalization also determines company culture aspects, such as whether employees have to sign in and out upon arriving and exiting the office, how many breaks workers can take and how long those breaks can be, how and when employees can use company computers and how workers at all levels are expected to dress for work.

History of Organizational Structure[5]

Organizational structures developed from the ancient times of hunters and collectors in tribal organizations through highly royal and clerical power structures to industrial structures and today's post-industrial structures.

As pointed out by Lawrence B. Mohr, the early theorists of organizational structure, Taylor, Fayol, and Weber "saw the importance of structure for effectiveness and efficiency and assumed without the slightest question that whatever structure was needed, people could fashion accordingly. Organizational structure was considered a matter of choice... When in the 1930s, the rebellion began that came to be known as human relations theory, there was still not a denial of the idea of structure as an artifact, but rather an advocacy of the creation of a different sort of structure, one in which the needs, knowledge, and opinions of employees might be given greater recognition." However, a different view arose in the 1960s, suggesting that the organizational structure is "an externally caused phenomenon, an outcome rather than an artifact."

In the 21st century, organizational theorists such as Lim, Griffiths, and Sambrook (2010) are once again proposing that organizational structure development is very much dependent on the expression of the strategies and behavior of the management and the workers as constrained by the power distribution between them, and influenced by their environment and the outcome.

Business Case for Organizational Structure[6]

A hallmark of a well-aligned organization is its ability to adapt and realign as needed. To ensure long-term viability, an organization must adjust its structure to fit new economic realities without diminishing core capabilities and competitive differentiation. Organizational realignment involves closing the structural gaps impeding organizational performance.

Problems created by a misaligned organizational structure

Rapid reorganization of business units, divisions or functions can lead to ineffective, misaligned organizational structures that do not support the business. Poorly conceived reorganizations may create significant problems, including the following:

- Structural gaps in roles, work processes, accountabilities and critical information flows can occur when companies eliminate middle management levels without eliminating the work, forcing employees to take on additional responsibilities.

- Diminished capacity, capability and agility issues can arise when a) lower-level employees who step in when middle management is eliminated are ill-equipped to perform the required duties and b) when higher-level executives must take on more tactical responsibilities, minimizing the value of their leadership skills.

- Disorganization and improper staffing can affect a company's cost structure, cash flow] and ability to deliver goods or services. Agile organizations can rapidly deploy people to address shifting business needs. With resources cut to the bone, however, most organizations' staff members can focus only on their immediate responsibilities, leaving little time, energy or desire to work outside their current job scope. Ultimately, diminished capacity and lagging response times affect an organization's ability to remain competitive.

- Declining workforce engagement can reduce retention, decrease customer loyalty and limit organizational performance and stakeholder value.

The importance of aligning the structure with the business Strategy

The key to profitable performance is the extent to which four business elements are aligned:

- Leadership. The individuals responsible for developing and deploying the strategy and monitoring results.

- Organization. The structure, processes and operations by which the strategy is deployed.

- Jobs. The necessary roles and responsibilities.

- People. The experience, skills and competencies needed to execute the strategy.

An understanding of the interdependencies of these business elements and the need for them to adapt to change quickly and strategically are essential for success in the high-performance organization. When these four elements are in sync, outstanding performance is more likely. The organizational design process is the pivotal connector between the business of the organization (e.g., top-level leadership and organizational strategy and goals) and forms of HR support (e.g., workflow process design, selection, development and compensation). Strategy must continually drive structure and people decisions, and the structure and design must reflect and enable effective leadership.

Achieving alignment and sustaining organizational capacity requires time and critical thinking. Organizations must identify outcomes the new structure or process is intended to produce. This typically requires recalibrating the following:

- Which work is mission-critical, can be scaled back or should be eliminated.

- Existing role requirements, while identifying necessary new or modified roles.

- Key metrics and accountabilities.

- Critical information flows.

- Decision Making authority by organization level.

Emerging Trends in Organizational Structure[7]

Except for the matrix organization, all the structures described above focus on the vertical organization; that is, who reports to whom, who has responsibility and authority for what parts of the organization, and so on. Such vertical integration is sometimes necessary, but may be a hindrance in rapidly changing environments. A detailed organizational chart of a large corporation structured on the traditional model would show many layers of managers; decision making flows vertically up and down the layers, but mostly downward. In general terms, this is an issue of interdependence.

In any organization, the different people and functions do not operate completely independently. To a greater or lesser degree, all parts of the organization need each other. Important developments in organizational design in the last few decades of the twentieth century and the early part of the twenty-first century have been attempts to understand the nature of interdependence and improve the functioning of organizations in respect to this factor. One approach is to flatten the organization, to develop the horizontal connections and de-emphasize vertical reporting relationships. At times, this involves simply eliminating layers of middle management. For example, some Japanese companies—even very large manufacturing firms—have only four levels of management: top management, plant management, department management, and section management. Some U.S. companies also have drastically reduced the number of managers as part of a downsizing strategy; not just to reduce salary expense, but also to streamline the organization in order to improve communication and decision making.

In a virtual sense, technology is another means of flattening the organization. The use of computer networks and software designed to facilitate group work within an organization can speed communications and decision making. Even more effective is the use of intranets to make company information readily accessible throughout the organization. The rapid rise of such technology has made virtual organizations and boundaryless organizations possible, where managers, technicians, suppliers, distributors, and customers connect digitally rather than physically.

A different perspective on the issue of interdependence can be seen by comparing the organic model of organization with the mechanistic model. The traditional, mechanistic structure is characterized as highly complex because of its emphasis on job specialization, highly formalized emphasis on definite procedures and protocols, and centralized authority and accountability. Yet, despite the advantages of coordination that these structures present, they may hinder tasks that are interdependent. In contrast, the organic model of organization is relatively simple because it de-emphasizes job specialization, is relatively informal, and decentralizes authority. Decision-making and goal-setting processes are shared at all levels, and communication ideally flows more freely throughout the organization.

A common way that modern business organizations move toward the organic model is by the implementation of various kinds of teams. Some organizations establish self-directed work teams as the basic production group. Examples include production cells in a manufacturing firm or customer service teams in an insurance company. At other organizational levels, cross-functional teams may be established, either on an ad hoc basis (e.g., for problem solving) or on a permanent basis as the regular means of conducting the organization's work. Aid Association for Lutherans is a large insurance organization that has adopted the self-directed work team approach. Part of the impetus toward the organic model is the belief that this kind of structure is more effective for employee motivation. Various studies have suggested that steps such as expanding the scope of jobs, involving workers in problem solving and planning, and fostering open communications bring greater job satisfaction and better performance.

Saturn Corporation (now defunct), a subsidiary of General Motors (GM), emphasized horizontal organization. It was started with a "clean sheet of paper," with the intention to learn and incorporate the best in business practices in order to be a successful U.S. auto manufacturer. The organizational structure that it adopted is described as a set of nested circles, rather than a pyramid. At the center is the self-directed production cell, called a Work Unit. These teams make most, if not all, decisions that affect only team members. Several such teams make up a wider circle called a Work Unit Module. Representatives from each team form the decision circle of the module, which makes decisions affecting more than one team or other modules. A number of modules form a Business Team, of which there are three in manufacturing. Leaders from the modules form the decision circle of the Business Team. Representatives of each Business Team form the Manufacturing Action Council, which oversees manufacturing. At all levels, decision making is done on a consensus basis, at least in theory. The president of Saturn, finally, reports to GM headquarters.

See Also

References

- ↑ Definition - What Does Organizational Structure Mean? Chron

- ↑ Centralized vs. Decentralized Organizational Structures Investopedia

- ↑ What are the Different Types of Organizational Structures? Business News Daily

- ↑ The Six Basic Elements of Organizational Structure Bizfluent

- ↑ History of Organizational Structure Wikipedia

- ↑ Making a Business Case for Organizational Structure SHRM

- ↑ Emerging Trends in Organizational Structure Reference for Business