Quality

What is Quality

Quality of a product or service is the extent to which it incorporates features and characteristics that allow the customer to use it - at satisfying their needs. Quality can also be defined as being fit for the intended purpose, or "fit for purpose". Another simple definition for quality is "conformance to requirements".[1]

Quality is both a perspective and an approach to increasing customer satisfaction, reducing cycle time and costs, and eliminating errors and rework using a set of defined tools such as Root Cause Analysis, Pareto Analysis, etc. The International Organization for Standardization (ISO) defines “Quality” as “the degree to which a set of inherent characteristics fulfills a requirement,” and “requirement” as “a need or expectation that is stated, generally implied or obligatory.” Examples of requirements include:

- Customer specifications such as reliability, availability, accuracy, and delivery dates.

- Value for goods and services purchased such as ROI and productivity gains.

- Various ISO standards relating to Quality including ISO 9001, IATF 16949, and ISO 13485.

- Statutory requirements such as the Food Safety Modernization Act, FDA code of federal regulations, Canadian Standards Association, Underwriters Laboratories, EU directives, and the Occupational Health & Safety Act.

- Various industry requirements.

Quality is not a program or a discipline. It doesn’t end when you have achieved a particular goal. Quality needs to live in the organization as the Culture of Quality in which every person experiences and understands the need for dedication to its values. Quality is a continuous race to improvement with no finish line. At a more general level, Quality is about doing the right thing for your customers, your employees, your stakeholders, your business, and the environment in which we all operate. From the level of the individual employee all the way up to the level of our planet, Quality is about maximizing productivity and delighting customers while protecting people and resources from the harm that results from shoddy processes and careless oversight. Quality is an approach that should be the goal of every organization from business and manufacturing to healthcare, government, and not-for-profits.

Dynamic Process of Achieving and Improving Quality[2]

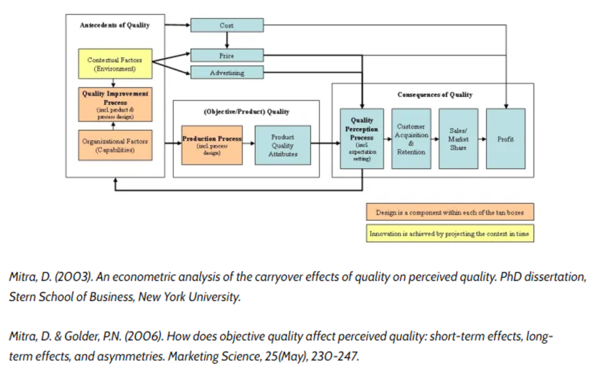

Debanjan Mitra, an Assistant Professor in the Department of Marketing at the University of Florida, a quality guru, noticed that across many disciplines, there were different perspectives on what quality was all about. To understand the meaning of quality from the marketing perspective, which is his interest, he investigated over 300 journal articles in different fields. He found that there were five stages of the dynamic process of achieving and improving quality:

- Organizational antecedents – creating an organization whose capabilities can support achieving world-class quality in products and services

- Operational antecedents – designing quality into products, managing processes to achieve quality

- Production quality – meeting specifications for features, reliability and performance; adequately addressing aesthetics and customer taste preferences to create demand

- Customer consequences of quality – whether and how customers perceive quality, and how this impacts retention

- Market consequences of quality – in terms of market share, as well as the impact of quality and quality improvement on its contribution to profitability and global competitiveness

Mitra’s Model (2003), incorporates the many implied aspects of the ISO 9000 para 3.1.5 definition of quality. Nicole Radziwill is Senior VP of Quality & Strategy at Ultranauts simplified his model in the illustration below:

Notable Definitions of Quality[3]

The definition of "quality" has changed over time, and even today some variance is found in how it is described. However, some commonality can still be found. The common element of the business definitions is that the quality of a product or service refers to the perception of the degree to which the product or service meets the customer's expectations. Quality has no specific meaning unless related to a specific function and/or object. The business meanings of quality have developed over time. Various interpretations are given below:

- American Society for Quality: "A combination of quantitative and qualitative perspectives for which each person has his or her own definition; examples of which include, "Meeting the requirements and expectations in service or product that were committed to" and "Pursuit of optimal solutions contributing to confirmed successes, fulfilling accountabilities". In technical usage, quality can have two meanings:

- a. The characteristics of a product or service that bear on its ability to satisfy stated or implied needs;

- b. A product or service free of deficiencies."

- Subir Chowdhury: "Quality combines people power and process power."

- Philip B. Crosby: "Conformance to requirements." The requirements may not fully represent customer expectations; Crosby treats this as a separate problem.

- W. Edwards Deming: concentrating on "the efficient production of the quality that the market expects, "and he linked quality and management: "Costs go down and productivity goes up as improvement of quality is accomplished by better management of design, engineering, testing and by improvement of processes.

- Peter Drucker: "Quality in a product or service is not what the supplier puts in. It is what the customer gets out and is willing to pay for."

- ISO 9000: "Degree to which a set of inherent characteristics fulfills requirements." The standard defines requirement as need or expectation.

- Joseph M. Juran: "Fitness for use." Fitness is defined by the customer.

- Noriaki Kano and others, present a two-dimensional model of quality: "must-be quality" and "attractive quality." The former is near to "fitness for use" and the latter is what the customer would love, but has not yet thought about. Supporters characterize this model more succinctly as: "Products and services that meet or exceed customers' expectations."

- Robert Pirsig: "The result of care."

- Six Sigma: "Number of defects per million opportunities."

- Genichi Taguchi, with two definitions:

- a. "Uniformity around a target value." The idea is to lower the standard deviation in outcomes and to keep the range of outcomes to a certain number of standard deviations, with rare exceptions.

- b. "The loss a product imposes on society after it is shipped." This definition of quality is based on a more comprehensive view of the production system.

- Gerald M. Weinberg: "Value to some person".

History of Quality[4]

The concept of Quality Management has its origins in the work of statistician Walter Shewhart, who was conducting research on the analysis of industrial processes while working at Bell Laboratories in the early 20th century. Shewhart realized manufacturing processes produced data that he could measure and analyze to determine their conformity to ideal standards of stability and control, and he could apply remedies that would bring any deviations back into line. This revolutionary approach highlighted the advantage of process-centered applications of Quality over older product-centered approaches. This concept is now referred to as statistical quality control (SQC) and is the backbone of the initial exploration of Quality in manufacturing.

In the 1940s, the Second World War prompted the American government to implement Quality standards based on SQC for military vendors.ix This improved Quality in the short term, but most civilian manufacturers failed to incorporate process improvement throughout their organizations. After the war, engineers W. Edwards Deming and Joseph M. Juran worked as consultants in Japan as Japanese industry worked to recover from the war and transform their economy to focus on the civilian production of goods and services. Deming and Juran worked with Japanese manufacturers to create the concept of Total Quality, in which Quality extends beyond the manufacturing process to all organizational processes and instills the values of Quality in every worker.x As a result of this Total Quality transformation, Japan became a manufacturing powerhouse, vastly increasing its market share at the expense of American manufacturers who had yet to recognize the value of Total Quality.

In the 1980s, American manufacturers and legislators began to recognize the crises of poor Quality in American manufacturing. The American response, built on Deming’s and Juran’s work in Japan, was Total Quality Management (TQM). The first ISO 9000 standard for Quality appeared in 1987, and it continues to be the globally recognized standard for Quality accreditation across many industries.

Since 2000, ISO 9000 has evolved to meet the needs of a changing marketplace. Globalization and emerging technologies have expanded both the scope of Quality and the tools used to meet Quality standards. New approaches, such as Six Sigma developed by Motorola, have achieved remarkable levels of productivity and variation reduction to produce goods and services that are free from defects. Quality is now seen as an approach that can be applied to any organization, including services, government, healthcare, education, and even nascent technology like Bitcoin and Blockchain.

Dimensions of Quality

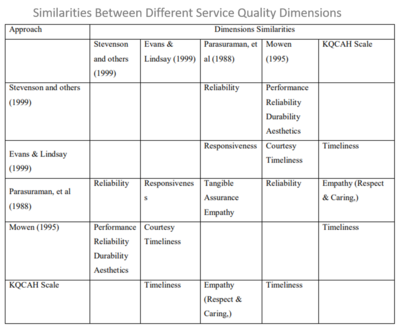

A number of scholars in the quality field have developed lists of dimensions that define quality for a product and/or a service. David Garvin developed a list of 8 dimensions of product quality. Evans and Lindsay provide a list of 8 dimensions of service quality. These are general lists and serve as good starting points. But, current research indicates that in terms of service quality, the dimensions are different for different industries. So Evans and Lindsay's list may not apply equally well to, for example, health care services, and food services. Parasuraman, et. al. developed a general list of 5 service dimensions that they tested in 4 types of service industries, but the applicability of these dimensions in other industries is unknown.[5]

Garvin proposes eight critical dimensions or categories of quality that can serve as a framework for strategic analysis: Performance, features, reliability, conformance, durability, serviceability, aesthetics, and perceived quality.

- Performance: Performance refers to a product's primary operating characteristics. For an automobile, performance would include traits like acceleration, handling, cruising speed, and comfort. Because this dimension of quality involves measurable attributes, brands can usually be ranked objectively on individual aspects of performance. Overall performance rankings, however, are more difficult to develop, especially when they involve benefits that not every customer needs.

- Features: Features are usually the secondary aspects of performance, the "bells and whistles" of products and services, those characteristics that supplement their basic functioning. The line separating primary performance characteristics from secondary features is often difficult to draw. What is crucial is that features involve objective and measurable attributes; objective individual needs, not prejudices, affect their translation into quality differences.

- Reliability: This dimension reflects the probability of a product malfunctioning or failing within a specified time period. Among the most common measures of reliability is the mean time to first failure, the mean time between failures, and the failure rate per unit of time. Because these measures require a product to be in use for a specified period, they are more relevant to durable goods than to products or services that are consumed instantly.

- Conformance: Conformance is the degree to which a product's design and operating characteristics meet established standards. The two most common measures of failure in conformance are defect rates in the factory and, once a product is in the hands of the customer, the incidence of service calls. These measures neglect other deviations from standards, like misspelled labels or shoddy construction, that does not lead to service or repair.

- Durability: A measure of product life, durability has both economic and technical dimensions. Technically, durability can be defined as the amount of use one gets from a product before it deteriorates. Alternatively, it may be defined as the amount of use one gets from a product before it breaks down and replacement is preferable to continued repair.

- Serviceability: Serviceability is speed, courtesy, competence, and ease of repair. Consumers are concerned not only about a product breaking down but also about the time before service is restored, the timeliness with which service appointments are kept, the nature of dealings with service personnel, and the frequency with which service calls or repairs fail to correct outstanding problems. In those cases where problems are not immediately resolved and complaints are filed, a company's complaints handling procedures are also likely to affect customers' ultimate evaluation of product and service quality.

- Aesthetics: Aesthetics is a subjective dimension of quality. How a product looks, feels, sounds, tastes, or smells is a matter of personal judgment and a reflection of individual preference. On this dimension of quality, it may be difficult to please everyone.

- Perceived Quality: Consumers do not always have complete information about a product's or service's attributes; indirect measures may be their only basis for comparing brands. A product's durability for example can seldom be observed directly; it must usually be inferred from various tangible and intangible aspects of the product. In such circumstances, images, advertising, and brand names - inferences about quality rather than the reality itself - can be critical.

A variety of frameworks and approaches have been applied to explain the multidimensional nature of service quality.

Parasuraman, et al (1988)

Parasuraman, et al (1988, p.23) proposed 5 service quality dimensions.

- Tangibles: Physical facilities, equipment, and appearance of personnel

- Reliability: Ability to perform the promised service dependably and accurately

- Responsiveness: Willingness to help customers and provide prompt service

- Assurance: Knowledge and courtesy of employees and their ability to inspire trust and confidence

- Empathy: Caring, individualized attention the firm provides its customers

These dimensions were developed and tested in many of service industries and proved to be applicable to many of them.

Mowen (1995)

Mowen (1995, p. 56) proposed eight dimensions of service quality

- Performance: The absolute level of performance of the good or service on the key attributes identified by customers.

- Number of attributes: The number of features/attributes offered

- Courtesy: The friendliness and empathy shown by people delivering the service or good.

- Reliability: The consistency of the performance of the good or service.

- Durability: The product's life span and general sturdiness.

- Timeliness: The speed with which the product is received or repaired; the speed with which the desired information is provided or service is received.

- Aesthetics: The physical appearance of the good; the attractiveness of the presentation of the service; the pleasantness of the atmosphere in which the service or product is received.

- Brand Equity: The additional positive or negative impact on the perceived quality that knowing the brand name has on the evaluation of perceived quality

Evans and Lindsay (1999)

Evans and Lindsay (1999, p.52) proposed 8 dimensions of service quality:

- Time; Customer waiting time.

- Timeliness; On-time completion.

- Completeness; Customers get all they ask for.

- Courtesy; Treatment by employees.

- Consistency; Same level of service for all customers.

- Accessibility and convenience; Ease of obtaining service.

- Accuracy; Performed correctly every time.

- Responsiveness: Reaction to special circumstances or requests.

Stevenson et al (1999)

Stevenson et al (1999. p 34) used Garvin’s 8 dimensions of product quality to assess service quality dimensions.

- Performance: The primary operating characteristics of a product.

- Features: The “bells and whistles” of a product (i.e., those characteristics that supplement the basic functions).

- Reliability: The probability that a product will fail within a specified period of time.

- Conformance: The degree to which the design or operating characteristics of a product meet pre-established standards.

- Durability: The amount of use a product can sustain before it physically deteriorates to the point where replacement is preferable to repair.

- Serviceability: Speed, courtesy, competence, and ease of repair.

- Aesthetics: The look, feel, taste, smell, and sound of a product.

- Perceived Quality: The impact of brand name, company image, and advertising.

KQCAH Scale (2001)

Sower et al, (2001, p.50) proposed 9 service quality dimensions: Efficacy, Appropriateness, Efficiency, Respect and Caring,

Safety Continuity Effectiveness Timeliness, and Availability

Abdullah (2014)

Abdullah (2014,p.67) argued that The performance assessment of the higher education service quality was based on five key areas which describe the status quo of academic performance of higher education institutions in the light of quality standards.

The key dimensions are:

- Organization and management of academic programs;

- Teaching and learning procedures;

- Resources and educational materials;

- Students support services;

- Skills development.

The Table below shows similarities between the different approaches that identified and classified service dimensions. It’s apparent that most of these approaches focus on similar dimensions, which are Reliability, Responsiveness, Timeliness, Performance, Durability, Empathy, Assurance, and Tangible. So the researcher used the serviqual five dimensions (Tangible, Reliability, Responsiveness, Assurance, and Empathy) to study service quality in higher education.

The Importance of Quality[6]

- To survive and thrive: Managing quality effectively can enhance the organization’s brand and reputation, protect it against risks, increase its efficiency, boost its profits and position it to keep on growing. All while making staff and customers happier.

- Quality is not just a box to be ticked or something you pay lip service to failures resulting from poor governance, ineffective assurance and resistance to change can, and do, have dire consequences for businesses, individuals, and society as a whole.

- Just ask BP: The company faces a total bill of £35bn from the Gulf of Mexico oil spill of 2010, which left 11 people dead, the region's environment devastated, and an indelible stain on BP's reputation.

- Or Volkswagen, which will be dealing with the fallout from the 2015 emissions cheating scandal for years to come (it's still too early to know how much it will cost them, but the amount will run to 10 figures at least).

- Or the retailers Tesco, Iceland, Aldi, and Lidl, whose reputations took a battering in 2013 when beef products were found to contain horsemeat.

- None of these things need have happened if the organization had been managing the quality of its outputs more effectively. But quality isn't just about disaster prevention – it's about achieving great results, and seizing opportunities to get better and better.

- Quality isn’t just an issue for commercial enterprises: Every organization has stakeholders of one kind or another whose needs they must strive to meet, which is what effective quality management is ultimately about.

Cost of Quality[7]

Cost of Quality (COQ) is a way of measuring the costs associated with ensuring that a Culture of Quality thrives in an organization, as well as the costs associated with Quality failures. There are four types of Quality-related costs:

- Prevention costs. These planned costs are the result of designing and implementing a QMS and preventing Quality problems from arising. These costs include Quality planning, training, and Quality assurance.

- Appraisal costs. These costs are the result of measuring the effectiveness of a Quality Management System and apply to both manufacturers and the supply chain. These costs include verification, Quality audits, and supplier assessment.

- Internal failure costs. These costs arise when the manufacturer discovers Quality failures before products or services are delivered to customers. They include waste from poor processes, excessive scrap, rework to correct errors, and the activity required to diagnose the cause of Quality failures.

- External failure costs. These are the most expensive costs and are usually apparent only after the products or services have reached the customer. These costs include repairs, warranty claims, returns, and dealing with customer complaints.

The Cost of Poor Quality (COPQ) and its consequences can be difficult for organizations to measure, and it can be a struggle to convince executive stakeholders that Quality improvement projects to mitigate COPQ have real value and are not simply cost centers. The primary consequences of COPQ are the most obvious. Costs associated with process failures inside the organization include:

- Excess scrap and waste material created by inefficient manufacturing processes,

- Rework defective or damaged products before they ship to market, and,

- Retesting and analyzing processes and procedures to determine the point of failure. If poor Quality is not caught before products or services make their way to end customers, the external costs can include those associated with:

- Lawsuits,

- Recalls,

- Warranties,

- Complaints,

- Returns,

- Repairs, and,

- Field support.

The traditional Cost of Poor Quality has usually been assumed to be between 4 percent and 5 percent of an organization’s annual revenue. In other words, a business with $100 million in annual revenue is throwing away between $4 million and $5 million by failing to mitigate the impact of preventable process failures.

Yet, like an iceberg, the visible surface of the problem masks something far deeper. Hidden costs associated with COPQ can include:

- Decreased employee engagement,

- Higher employee turnover and attrition,

- Employees addressing Quality failures instead of focusing on Quality improvement through innovation,

- Overtime costs,

- Machine downtime,

- Long-term customer dissatisfaction,

- Brand damage,

- Poor inventory turnover, and,

- Decreased customer lifetime value.

When we account for these hidden and long-term costs, COPQ is more like 10 percent to 25 percent of an organization’s annual revenue. To put that into perspective again, that would mean a company with $10 million in annual revenue is throwing away $1 million to $2.5 million every year on failures that are predictable and preventable. These costs are often passed on to customers in the form of a higher price tag, which leads to additional customer dissatisfaction and brand damage. Investing in Quality is therefore the most effective way of reducing these staggering costs.

Quality Management[8]

In business, there are many aspects to quality. It may refer either to goods or services. The key aspects of how good or 'fit for purpose' goods are rooted in the concept of quality management, which covers four areas:

- Quality planning: This is a means of developing the goods, systems, and processes required to meet consumer expectations. In many cases, the producer tries to exceed them.

- Quality assurance or QA: QA is a program for the systematic monitoring of all aspects of production, a project, or a service. The aim is to make sure that the producer and what the producer makes meet the required standards.

- Quality control or QA: QC is a system in manufacturing of maintaining standards. Here, the focus is on the finished product, i.e., making sure it is defect-free and meets specifications and standards. While QC focuses on what happens after the producer makes the product, QA focuses on what happens before completion.

- Quality improvement or QI: QI is the systematic approach to the elimination of waste and losses in the production process. Sometimes, it also includes the reduction of waste and losses. QI involves weeding out what is not working properly, and either improving it or getting rid of it.

Measuring Quality[9]

- Quality is specification driven – does it meet the set performance requirements

- Quality is measured at the start of life – percent passing specification acceptance

- Quality effectiveness is observable by the number of rejects from customers

The quality characteristics of a product or service are known as the ‘Determinants of Quality’. These are the attributes customers look for to decide if it is a quality product or service.

Quality and Governance Relationship

There is often a connection between quality and governance in that good governance practices can help ensure that a company delivers high-quality products or services to its customers.

Some key elements of good governance that can contribute to quality include:

- Clear policies and procedures: Having well-defined policies and procedures in place can help ensure that a company's operations are consistent and reliable, which can lead to higher-quality products or services.

- Effective oversight: Strong oversight mechanisms, such as the board of directors or internal audit functions, can help ensure that a company's operations are aligned with its goals and are carried out in an ethical and transparent manner.

- Effective risk management: Good risk management practices can help a company identify and mitigate potential issues that could affect the quality of its products or services.

- Clear communication: Effective communication throughout the organization can help ensure that everyone is working towards the same goals and that any issues or concerns are addressed in a timely manner.

Good governance practices can help a company build and maintain a culture of quality, which can lead to more satisfied customers and better business outcomes.

Quality and Information Technology

Information Technology (IT) supports and enhances the quality of products or services. IT systems can be used to automate and streamline processes, which can help reduce errors and improve efficiency. IT can also be used to collect and analyze data, which can help a company identify and resolve quality issues more quickly.

Some key ways in which IT can support quality include:

- Quality assurance: IT systems can be used to automate quality assurance processes, such as testing and inspection, which can help reduce errors and improve efficiency.

- Quality control: IT systems can be used to monitor processes and identify potential quality issues in real-time, which can help a company take corrective action before problems occur.

- Quality management: IT systems can be used to manage and track quality-related data, such as customer complaints or defects, which can help a company identify trends and areas for improvement.

- Customer satisfaction: IT systems can be used to collect and analyze customer feedback, which can help a company identify and resolve quality issues and improve customer satisfaction.

See Also

- Quality Assurance (QA)

- Quality Competitive Index (QCi) Model

- Quality Management System (QMS)

- Quality Control (QC)

- Quality Function Deployment (QFD)

- Quality Management

- Quality Management Maturity Grid (QMMG)

- Continuous Quality Improvement (CQI)

- Total Quality Management (TQM)

- Information Quality Management (IQM)

- Data Quality

- Seven Basic Tools of Quality