Sarbanes Oxley Act (SOX)

The Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002, sponsored by Paul Sarbanes and Michael Oxley, represents a huge change to federal securities law. It came as a result of the corporate financial scandals involving Enron, WorldCom and Global Crossing. Effective in 2006, all publicly-traded companies are required to implement and report internal accounting controls to the SEC for compliance. In addition, certain provisions of Sarbanes-Oxley also apply to privately-held companies. Executives who approve shoddy or inaccurate documentation face fines of up to $5 million and jail time of up to 20 years.[1]

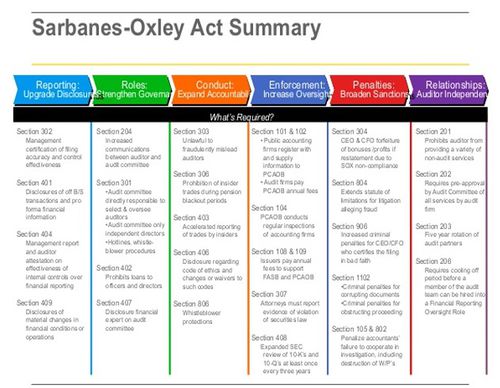

The rules and enforcement policies outlined by the SOX Act of 2002 amend or supplement existing legislation dealing with security regulations. The Act swept reforms in the following four areas:

- Corporate Responsibility

- Increased Criminal Punishment

- Accounting Regulation

- New Protections[2]

Sarbanes Oxley Act - Historical Overview

History and Context of Sarbanes Oxley Act[3]

A variety of complex factors created the conditions and culture in which a series of large corporate frauds occurred between 2000–2002. The spectacular, highly publicized frauds at Enron, WorldCom, and Tyco exposed significant problems with conflicts of interest and incentive compensation practices. The analysis of their complex and contentious root causes contributed to the passage of SOX in 2002. In a 2004 interview, Senator Paul Sarbanes stated:

The Senate Banking Committee undertook a series of hearings on the problems in the markets that had led to a loss of hundreds and hundreds of billions, indeed trillions of dollars in market value. The hearings set out to lay the foundation for legislation. We scheduled 10 hearings over a six-week period, during which we brought in some of the best people in the country to testify ... The hearings produced remarkable consensus on the nature of the problems: inadequate oversight of accountants, lack of auditor independence, weak corporate governance procedures, stock analysts' conflict of interests, inadequate disclosure provisions, and grossly inadequate funding of the Securities and Exchange Commission.

- Auditor conflicts of interest: Prior to SOX, auditing firms, the primary financial "watchdogs" for investors, were self-regulated. They also performed significant non-audit or consulting work for the companies they audited. Many of these consulting agreements were far more lucrative than the auditing engagement. This presented at least the appearance of a conflict of interest. For example, challenging the company's accounting approach might damage a client relationship, conceivably placing a significant consulting arrangement at risk, damaging the auditing firm's bottom line.

- Boardroom failures: Boards of Directors, specifically Audit Committees, are charged with establishing oversight mechanisms for financial reporting in U.S. corporations on the behalf of investors. These scandals identified Board members who either did not exercise their responsibilities or did not have the expertise to understand the complexities of the businesses. In many cases, Audit Committee members were not truly independent of management.

- Securities analysts' conflicts of interest: The roles of securities analysts, who make buy and sell recommendations on company stocks and bonds, and investment bankers, who help provide companies loans or handle mergers and acquisitions, provide opportunities for conflicts. Similar to the auditor conflict, issuing a buy or sell recommendation on a stock while providing lucrative investment banking services creates at least the appearance of a conflict of interest.

- Inadequate funding of the SEC: The SEC budget has steadily increased to nearly double the pre-SOX level. In the interview cited above, Sarbanes indicated that enforcement and rule-making are more effective post-SOX.

- Banking practices: Lending to a firm sends signals to investors regarding the firm's risk. In the case of Enron, several major banks provided large loans to the company without understanding, or while ignoring, the risks of the company. Investors of these banks and their clients were hurt by such bad loans, resulting in large settlement payments by the banks. Others interpreted the willingness of banks to lend money to the company as an indication of its health and integrity, and were led to invest in Enron as a result. These investors were hurt as well.

- Internet bubble: Investors had been stung in 2000 by the sharp declines in technology stocks and to a lesser extent, by declines in the overall market. Certain mutual fund managers were alleged to have advocated the purchasing of particular technology stocks, while quietly selling them. The losses sustained also helped create a general anger among investors.

- Executive compensation: Stock option and bonus practices, combined with volatility in stock prices for even small earnings "misses," resulted in pressures to manage earnings. Stock options were not treated as compensation expense by companies, encouraging this form of compensation. With a large stock-based bonus at risk, managers were pressured to meet their targets.

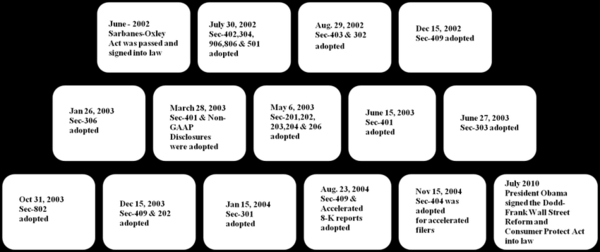

SOX Timeline

The figure below presents the timeline for the implementation of the SOX Act

source: Abayomi Alase

Components of SOX

Principal components of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002[4]

- Established independent oversight of public company audits

- Established the PCAOB, which ended more than 100 years of self-regulation by the public company audit profession

- Provided the PCAOB with inspection, enforcement and standard-setting authority

- Strengthened audit committees and corporate governance

- Required audit committees, independent of management, for all listed companies

- Required the independent audit committee, rather than management, to be directly responsible for the appointment, compensation and oversight of the external auditor

- Required disclosure of whether at least one “financial expert” is on the audit committee

- Enhanced transparency, executive accountability and investor protection

- Required audit firms to disclose certain information about their operations for the first time, including names of clients, fees and quality control procedures

- Required the CEO and CFO to certify financial reports

- Prohibited corporate officers and directors from fraudulently misleading auditors

- Instituted clawback provisions for CEO and CFO pay after financial restatements

- Established protection for whistleblowers employed by public companies who report accounting, auditing and internal control irregularities

- Required management to assess the effectiveness of internal controls over financial reporting (404(a)) and auditors to attest to management’s representations (404(b))

- Established the “Fair Funds” program at the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) to augment the funds available to compensate victims of securities fraud

- Enhanced auditor independence

- Prohibited audit firms from providing certain non-audit services to audited companies

- Required audit committee pre-approval of all audit and non-audit services

- Required lead audit partner rotation every five years rather than every seven years

Key Sections of the Sarbanes Oxley Act

The Sarbanes-Oxley Act is arranged into eleven titles. As far as compliance is concerned, the most important sections within these are often considered to be 302, 401, 404, 409, 802 and 906.

Key Sections[5]

- Section 201 outlines Prohibited Auditor Activities.

- Section 302 describes the CEO’s and CFO’s new responsibilities regarding corporate reports.

- Section 404 addresses the Management Assessment of Internal Controls.

- Section 409 outlines Real Time Disclosure.

- Section 802 describes criminal penalties for altering documents.

- Section 806 describes whistleblower protection.

- Section 807 describes criminal penalties for fraud.

- Section 906 addresses criminal penalties for certifying a misleading or fraudulent financial report.

Sarbanes-Oxley Act: Key Provisions

The Key Provisions of SOX[6]

Sarbanes-Oxley made numerous reforms to corporate financial reporting and the accounting profession. SOX requires corporate executives to certify the accuracy of their company's financial statements; maintain and assess internal controls to prevent wrong, misleading, or fraudulent financial data; and imposes criminal penalties for misleading shareholders and altering documents to impede an investigation. Sarbanes-Oxley also established an oversight board for the accounting profession, regulates the relationship between corporations and accounting firms, and shields corporate whistleblowers from retaliation.

- Executives Must Certify Financial Statements: Sarbanes-Oxley requires a public company's chief executive officer and chief financial officer to certify the accuracy of its financial reports. These executives are required to certify that they've reviewed the financial reports, that the reports are accurate, and that the company has internal controls in place to ensure accurate financial disclosures and prevent fraud and misrepresentation.

- Companies Maintain Internal Controls to Prevent Fraud: Sarbanes-Oxley requires companies to develop internal controls to ensure the accuracy of its financial reports. Each financial report contains an internal control report, and a company's annual year-end report assesses the effectiveness of those internal controls. A company's external auditor is required to attest to this internal control assessment as well.

- The Public Company Accounting Oversight Board: Sarbanes-Oxley established the Public Company Accounting Oversight Board (PCAOB). This non-profit, private sector board regulates accountants auditing pubic companies - a significant proportion of all accountants. The PCAOB can issue rules and regulations related to accounting. Before SOX, the accounts were a self-regulated profession similar to medical professionals and lawyers.

- Criminal Penalties: New criminal offenses and enhanced penalties for corporate fraud and related misdeeds were enacted as well. Sarbanes-Oxley makes it a crime to defraud shareholders of publicly traded companies through the filing of misleading financial reports. Executives face fines of up to $1 million and ten years imprisonment for knowingly certifying financial reports that don't comply with the SOX's requirements. Those penalties are enhanced for executives who "willfully" certify noncompliant financial reports: they face fines of up to $5 million and up to twenty years imprisonment. Sarbanes-Oxley also criminalizes the falsification and destruction of records to impede or influence an investigation.

- Whistleblower Protections: Sarbanes-Oxley also took steps to protect employees who report corporate fraud, also known as whistleblowers. The act prohibits retaliation against whistleblowers who lawfully report corporate misdeeds. Companies may not "discharge, demote, suspend, threaten, harass, or discriminate against" employees who provide information to investigators or testify in enforcement proceedings. SOX created a civil action for employees who are subjected to retaliation, allowing them to sue an employer for violating this provision.

See Also

Governance

IT Governance

Compliance

Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB)

Financial Analysis

Risk Management

Data Governance

References

- ↑ Definition: What is Sarbanes Oxley Act (SOX)? Sarbans Oxley 101

- ↑ Expalining Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002 (SOX) Investopedia

- ↑ History and Context of Sarbanes Oxley Act Wikipedia

- ↑ Principal components of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002 E&Y

- ↑ Key Sections of the Sarbanes Oxley Act Sox Online

- ↑ What are the Key Provisions of SOX? Findlaw

Further Reading

- Sarbanes Oxley (SOX) and the Procurement Function: Let Us View Compliance as an Opportunity Infosys

- Is it time to pull your SOX up? Navigate the Transformative Age Neil Mathur

- The Costs And Benefits Of Sarbanes-Oxley Forbes

- Understanding the Sarbanes-Oxley Act and Its Impact Mary Heisz, Devin Scarrow