Value Chain

A value chain is a high-level model developed by Michael Porter used to describe the process by which businesses receive raw materials, add value to the raw materials through various processes to create a finished product, and then sell that end product to customers. Companies conduct Value Chain Analysis by looking at every production step required to create a product and identifying ways to increase the efficiency of the chain. The overall goal is to deliver maximum value for the least possible total cost and create a competitive advantage.[1]

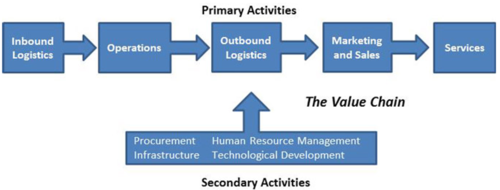

Porter's Value Chain (Figure 1.) – the seminal ‘business school definition’[2]

“The idea of the value chain is based on the process view of organizations, the idea of seeing a manufacturing (or service) organization as a system, made up of subsystems each with inputs, transformation processes, and outputs. Inputs, transformation processes, and outputs involve the acquisition and consumption of resources - money, labor, materials, equipment, buildings, land, administration and management]]. How value chain activities are carried out determines costs and affects profits. Most organizations engage in hundreds, even thousands, of activities in the process of converting inputs to outputs. According to Porter (1985) these activities can be classified generally as either primary or support activities that all businesses must undertake in some form.”

Figure 1. source: Cambridge Institute for Sustainability Leadership

Most organizations engage in hundreds, even thousands, of activities in the process of converting inputs to outputs. These activities can be classified generally as either primary or support activities that all businesses must undertake in some form. According to Porter (1985), the primary activities are:

- Inbound Logistics - involve relationships with suppliers and include all the activities required to receive, store, and disseminate inputs.

- Operations - are all the activities required to transform inputs into outputs (products and services).

- Outbound Logistics - include all the activities required to collect, store, and distribute the output.

- Marketing and Sales - activities inform buyers about products and services, induce buyers to purchase them, and facilitate their purchase.

- Service - includes all the activities required to keep the product or service working effectively for the buyer after it is sold and delivered.

Secondary activities are:

- Procurement - is the acquisition of inputs, or resources, for the firm.

- Human Resource management - consists of all activities involved in recruiting, hiring, training, developing, compensating, and (if necessary) dismissing or laying off personnel.

- Technological Development - pertains to the equipment, hardware, software, procedures, and technical knowledge brought to bear in the firm's transformation of inputs into outputs.

- Infrastructure - serves the company's needs and ties its various parts together, it consists of functions or departments such as accounting, legal, finance, planning, public affairs, government *relations, quality assurance, and general management.[3]

Value Chains - Basic Definitions and Context[4]

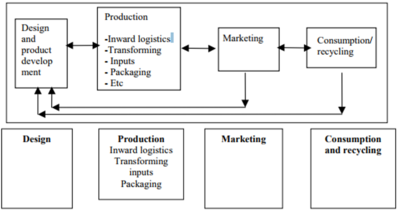

- The Simple Value Chain (Figure 2.)

The value chain describes the full range of activities that are required to bring a product or service from conception, through the different phases of production (involving a combination of physical transformation and the input of various producer services), delivery to final consumers, and final disposal after use. Considered in its general form, it takes the shape described in Figure 1. As can be seen from this, production per se is only one of a number of value-added links. Moreover, there are ranges of activities within each link of the chain. Although often depicted as a vertical chain, intra-chain linkages are most often of a two-way nature – for example, specialized design agencies not only influence the nature of the production process and marketing but are in turn influenced by the constraints in these downstream links in the chain.

Figure 2. source: IDRC

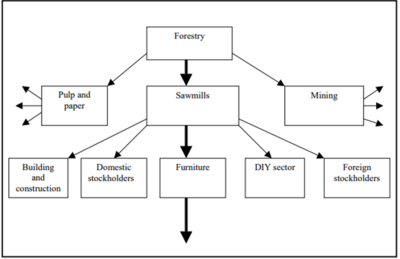

- The Extended Value Chain (Figure 3.)

In the real world, of course, value chains are much more complex than this. For one thing, there tend to be many more links in the chain. Take, for example, the case of the furniture industry (Figure 3). This involves the provision of seed inputs, chemicals, equipment, and water for the forestry sector. Cut logs pass to the sawmill sector which gets its primary inputs from the machinery sector. From there, sawn timber moves to the furniture manufacturers who, in turn, obtain inputs from the machinery, adhesives, and paint industries and also draw on design and branding skills from the service sector. Depending on which market is served, the furniture then passes through various intermediary stages until it reaches the final customer, who after use, consigns the furniture for recycling.

Figure 3. source: IDRC

- One or many value chains (Figure 4.)

In addition to the manifold links in a value chain, typically intermediary producers in a particular value chain may feed into a number of different value chains (Figure 4). In some cases, these alternative value chains may absorb only a small share of their output; in other cases, there may be an equal spread of customers. But the share of sales at a particular point in time may not capture the full story – the dynamics of a particular market or technology may mean that a relatively small (or large) customer/supplier may become a relatively large (small) customer/supplier in the future. Furthermore, the share of sales may obscure the crucial role that a particular supplier controlling a key core technology or input (which may be a relatively small part of its output) has on the rest of the value chain.

Figure 4. source: IDRC

Significance of Value Chain[5]

The value chain framework quickly made its way to the forefront of management thought as a powerful analysis tool for strategic planning. The simpler concept of value streams, a cross-functional process that was developed over the next decade,[13] had some success in the early 1990s. The value-chain concept has been extended beyond individual firms. It can apply to whole supply chains and distribution networks. The delivery of a mix of products and services to the end customer will mobilize different economic factors, each managing its own value chain. The industry-wide synchronized interactions of those local value chains create an extended value chain, sometimes global in extent. Porter terms this larger interconnected system of value chains as the "value system". A value system includes the value chains of a firm's supplier (and their suppliers all the way back), the firm itself, the firm distribution channels, and the firm's buyers (and presumably extended to the buyers of their products, and so on). Capturing the value generated along the chain is the new approach taken by many management strategists. For example, a manufacturer might require its parts suppliers to be located nearby its assembly plant to minimize the cost of transportation. By exploiting the upstream and downstream information flowing along the value chain, the firms may try to bypass the intermediaries creating new business models, or in other ways creating improvements in their value system. Value chain analysis has also been successfully used in large petrochemical plant maintenance organizations to show how to work selection, work planning, work scheduling, and finally, work execution can (when considered as elements of chains) help drive lean approaches to maintenance. The Maintenance Value Chain approach is particularly successful when used as a tool for helping change management as it is seen as more user-friendly than other business process tools. A value chain approach could also offer a meaningful alternative to evaluate private or public companies when there is a lack of publicly known data from direct competition, where the subject company is compared with, for example, a known downstream industry to have a good feel of its value by building useful correlations with its downstream companies.

Using Porter's Value Chain[6]

To identify and understand your company's value chain, follow these steps.

- Step 1 – Identify subactivities for each primary activity: For each primary activity, determine which specific subactivities create value. There are three different types of subactivities:

- Direct activities create value by themselves. For example, in a book publisher's marketing and sales activity, direct subactivities include making sales calls to bookstores, advertising, and selling online.

- Indirect activities allow direct activities to run smoothly. For the book publisher's sales and marketing activity, indirect subactivities include managing the sales force and keeping customer records.

- Quality assurance activities ensure that direct and indirect activities meet the necessary standards. For the book publisher's sales and marketing activity, this might include proofreading and editing advertisements.

- Step 2 – Identify subactivities for each support activity: For each of the Human Resource Management, Technology Development, and Procurement support activities, determine the subactivities that create value within each primary activity. For example, consider how human resource management adds value to inbound logistics, operations, outbound logistics, and so on. As in Step 1, look for direct, indirect, and quality assurance subactivities. Then identify the various value-creating subactivities in your company's infrastructure. These will generally be cross-functional in nature, rather than specific to each primary activity. Again, look for direct, indirect, and quality assurance activities.

- Step 3 – Identify links: Find the connections between all of the value activities you've identified. This will take time, but the links are key to increasing competitive advantage from the value chain framework. For example, there's a link between developing the sales force (an HR investment) and sales volumes. There's another link between order turnaround times, and service phone calls from frustrated customers waiting for deliveries.

- Step 4 – Look for opportunities to increase value: Review each of the subactivities and links that you've identified, and think about how you can change or enhance it to maximize the value you offer to customers (customers of support activities can be internal as well as external).