Social Engineering

What is Social Engineering?

Social Engineering is the art of manipulating people so they give up confidential information. The types of information these criminals are seeking can vary, but when individuals are targeted the criminals are usually trying to trick you into giving them your passwords or bank information, or access your computer to secretly install malicious software–that will give them access to your passwords and bank information as well as giving them control over your computer. Criminals use social engineering tactics because it is usually easier to exploit your natural inclination to trust than it is to discover ways to hack your software. For example, it is much easier to fool someone into giving you their password than it is for you to try hacking their password (unless the password is really weak).[1]

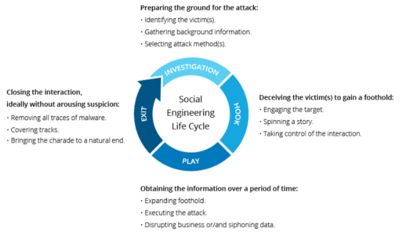

Social engineering attacks happen in one or more steps. A perpetrator first investigates the intended victim to gather necessary background information, such as potential points of entry and weak security protocols, needed to proceed with the attack. Then, the attacker moves to gain the victim’s trust and provide stimuli for subsequent actions that break security practices, such as revealing sensitive information or granting access to critical resources.[2]

What makes social engineering especially dangerous is that it relies on human error, rather than vulnerabilities in software and operating systems. Mistakes made by legitimate users are much less predictable, making them harder to identify and thwart than a malware-based intrusion.

The Why and How of Social Engineering[3]

Social engineers are a modern day form of fraudsters or con artists. They may attempt to access computer networks or data stores by gaining the confidence of authorized users or stealing those users’ credentials in order to masquerade as trusted insiders. It is common for social engineers to rely on the natural helpfulness of people or to attempt to exploit their perceived personality weaknesses. For example, they may call with a feigned urgent problem that requires immediate network access. Social engineers have been known to appeal to vanity, authority, greed, or other information gleaned from eavesdropping or online sleuthing, often via social media.

Cyber criminals use social engineering tactics in order to convince people to open email attachments infected with malware, persuade unsuspecting individuals to divulge sensitive information, or even scare people into installing and running malware.

Types of Social Engineering Attacks[4]

- Baiting: This type of social engineering depends upon a victim taking the bait, not unlike a fish reacting to a worm on a hook. The person dangling the bait wants to entice the target into taking action.

- Example: A cybercriminal might leave a USB stick, loaded with malware, in a place where the target will see it. In addition, the criminal might label the device in a compelling way — “Confidential” or “Bonuses.” A target who takes the bait will pick up the device and plug it into a computer to see what’s on it. The malware will then automatically inject itself into the computer.

- Phishing: Phishing is a well-known way to grab information from an unwitting victim. Despite its notoriety, it remains quite successful. The perpetrator typically sends an email or text to the target, seeking information that might help with a more significant crime.

- Example: A fraudster might send emails that appear to come from a source trusted by the would-be victims. That source might be a bank, for instance, asking email recipients to click on a link to log in to their accounts. Those who click on the link, though, are taken to a fake website that, like the email, appears to be legitimate. If they log in at that fake site, they’re essentially handing over their login credentials and giving the crook access to their bank accounts. In another form of phishing, known as spear phishing, the fraudster tries to target — or “spear” — a specific person. The criminal might track down the name and email of, say, a human resources person within a particular company. The criminal then sends that person an email that appears to come from a high-level company executive. Some recent cases involved an email request for employee W-2 data, which includes names, mailing addresses, and Social Security numbers. If the fraudster is successful, the victim will unwittingly hand over information that could be used to steal the identities of dozens or even thousands of people.

- Email hacking and contact spamming: It’s in our nature to pay attention to messages from people we know. Some criminals try to take advantage of this by commandeering email accounts and spamming account contact lists.

- Example: If your friend sent you an email with the subject, “Check out this site I found, it’s totally cool,” you might not think twice before opening it. By taking over someone’s email account, a fraudster can make those on the contact list believe they’re receiving email from someone they know. The primary objectives include spreading malware and tricking people out of their data.

- Pretexting: Pretexting is the use of an interesting pretext — or ploy — to capture someone’s attention. Once the story hooks the person, the fraudster tries to trick the would-be victim into providing something of value.

- Example: Let’s say you received an email, naming you as the beneficiary of a will. The email requests your personal information to prove you’re the actual beneficiary and to speed the transfer of your inheritance. Instead, you’re at risk of giving a con artist the ability not to add to your bank account, but to access and withdraw your funds.

- Quid pro quo: This scam involves an exchange — I give you this, and you give me that. Fraudsters make the victim believe it’s a fair exchange, but that’s far from the case, as the cheat always comes out on top.

- Example: A scammer may call a target, pretending to be an IT support technician. The victim might hand over the login credentials to their computer, thinking they’re receiving technical support in return. Instead, the scammer can now take control of the victim’s computer, loading it with malware or, perhaps, stealing personal information from the computer to commit identity theft.

- Vishing: Vishing is the voice version of phishing. “V” stands for voice, but otherwise, the scam attempt is the same. The criminal uses the phone to trick a victim into handing over valuable information.

- Example: A criminal might call an employee, posing as a co-worker. The criminal might prevail upon the victim to provide login credentials or other information that could be used to target the company or its employees. Something else to keep in mind about social engineering attacks is that cyber criminals can take one of two approaches to their crimes. They often are satisfied by a one-off attack, known as hunting. But they can also think long-term, a method known as farming. As the short form of attacks, hunting is when cyber criminals use phishing, baiting and other types of social engineering to extract as much data as possible from the victim with as little interaction as possible. Farming is when a cybercriminal seeks to form a relationship with their target. The attacker’s goal, then, is to string along the victim for as long as possible in order to extract as much data as possible.

Principles of Social Engineering[5]

Social engineering relies heavily on the 6 principles of influence established by Robert Cialdini. Cialdini's theory of influence is based on six key principles: reciprocity, commitment and consistency, social proof, authority, liking, scarcity.

- Reciprocity – People tend to return a favor, thus the pervasiveness of free samples in marketing. In his conferences, he often uses the example of Ethiopia providing thousands of dollars in humanitarian aid to Mexico just after the 1985 earthquake, despite Ethiopia suffering from a crippling famine and civil war at the time. Ethiopia had been reciprocating the diplomatic support Mexico provided when Italy invaded Ethiopia in 1935. The good cop/bad cop strategy is also based on this principle.

- Commitment and consistency – If people commit, orally or in writing, to an idea or goal, they are more likely to honor that commitment because they have stated that that idea or goal fits their self-image. Even if the original incentive or motivation is removed after they have already agreed, they will continue to honor the agreement. Cialdini notes Chinese brainwashing of American prisoners of war to rewrite their self-image and gain automatic unenforced compliance. Another example is marketers who make the user close popups by saying “I’ll sign up later” or "No thanks, I prefer not making money”.

- Social proof – People will do things that they see other people are doing. For example, in one experiment, one or more confederates would look up into the sky; bystanders would then look up into the sky to see what they were missing. At one point this experiment was aborted, as so many people were looking up that they stopped traffic. See conformity, and the Asch conformity experiments.

- Authority – People will tend to obey authority figures, even if they are asked to perform objectionable acts. Cialdini cites incidents such as the Milgram experiments in the early 1960s and the My Lai massacre.

- Liking – People are easily persuaded by other people whom they like. Cialdini cites the marketing of Tupperware in what might now be called viral marketing. People were more likely to buy if they liked the person selling it to them. Some of the many biases favoring more attractive people are discussed. See physical attractiveness stereotype.

- Scarcity – Perceived scarcity will generate demand. For example, saying offers are available for a "limited time only" encourages sales.

Famous social Engineering Attacks[6]

A good way to get a sense of what social engineering tactics you should look out for is to know about what's been used in the past. We've got all the details in an extensive article on the subject, but for the moment let's focus on three social engineering techniques — independent of technological platforms — that have been successful for scammers in a big way.

- Offer something sweet. As any con artist will tell you, the easiest way to scam a mark is to exploit their own greed. This is the foundation of the classic Nigerian 419 scam, in which the scammer tries to convince the victim to help get supposedly ill-gotten cash out of their own country into a safe bank, offering a portion of the funds in exchange. These "Nigerian prince" emails have been a running joke for decades, but they're still an effective social engineering technique that people fall for: in 2007 the treasurer of a sparsely populated Michigan county gave $1.2 million in public funds to such a scammer in the hopes of personally cashing in. Another common lure is the prospect of a new, better job, which apparently is something far too many of us want: in a hugely embarassing 2011 breach, the security company RSA was compromised when at least two low-level employees opened a malware file attached to a phishing email with the file name "2011 recruitment plan.xls."

- Fake it till you make it. One of the simplest — and surprisingly most successful — social engineering techniques is to simply pretend to be your victim. In one of Kevin Mitnick's legendary early scams, he got access to Digital Equipment Corporation's OS development servers simply by calling the company, claiming to be one of their lead developers, and saying he was having trouble logging in; he was immediately rewarded with a new login and password. This all happened in 1979, and you'd think things would've improved since then, but you'd be wrong: in 2016, a hacker got control of a U.S. Department of Justice email address and used it to impersonate an employee, coaxing a help desk into handing over an access token for the DoJ intranet by saying it was his first week on the job and he didn't know how anything worked. Many organizations do have barriers meant to prevent these kinds of brazen impersonations, but they can often be circumvented fairly easily. When Hewlett-Packard in hired private investigators to find out which HP board members were leaking info to the press in 2005, they were able to supply the PIs with the last four digits of their targets' social security number — which AT&T's tech support accepted as proof of ID before handing over detailed call logs.

- Act like you're in charge. Most of us are primed to respect authority — or, as it turns out, to respect people who act like they have the authority to do what they're doing. You can exploit varying degrees of knowledge of a company's internal processes to convince people that you have the right to be places or see things that you shouldn't, or that a communication coming from you is really coming from someone they respect. For instance, in 2015 finance employees at Ubiquiti Networks wired millions of dollars in company money to scam artists who were impersonating company executives, probably using a lookalike URL in their email address. On the lower tech side, investigators working for British tabloids in the late '00s and early '10s often found ways to get access to victims' voicemail accounts by pretending to be other employees of the phone company via sheer bluffing; for instance, one PI convinced Vodafone to reset actress Sienna Miller's voicemail PIN by calling and claiming to be "John from credit control." Sometimes it's external authorities whose demands we comply with without giving it much thought. Hillary Clinton campaign honcho John Podesta had his email hacked by Russian spies in 2016 when they sent him a phishing email disguised as a note from Google asking him to reset his password. By taking action that he thought would secure his account, he actually gave his login credentials away.

Protecting Against Social engineering[7]

- Turn your spam filter on. A lot of social engineering happens via email so the easiest way to protect against it is to block spam from making its way to your inbox. Legitimate emails will sometimes end up in your spam folder, but you can prevent this from happening in the future by flagging these emails as “not spam,” and adding legitimate senders to your contacts list.

- Learn how to spot phishing emails. Talented scammers spend a lot of time spoofing emails to look like the real thing, but with a little due diligence you can easily spot the spoofs.

- The sender’s address doesn’t match the domain for the company they claim to represent. In other words, emails from PayPal always come from [email protected] and emails from Microsoft always come from [email protected].

- The sender doesn’t seem to actually know who you are. Legitimate emails from companies and people you know will be addressed to you by name. Phishing emails often use generic salutations like “customer” or “friend.”

- Embedded links have unusual URLs. Vet the URL before clicking by hovering over it with your cursor. If the link looks suspicious, navigate to the website directly via your browser. Same for any call-to-action buttons. Hover over them with your mouse before clicking. If you’re on a mobile device, navigate to the site directly or via the dedicated app.

- The email has typos, bad grammar, and unusual syntax. Does it look like the email was translated with Google Translate? There’s a good chance it was.

- The email is too good to be true. Advance-fee scams work because they offer a huge reward in exchange for very little work. But if you take some time to actually think about the email, the offer is fake or outright illegal.

- Turn macros off. Turning off macros will prevent malware-laden email attachments from infecting your computer. And if someone emails you an attachment and the document asks you to “enable macros,” click “no,” especially if you don’t know the sender. If you suspect it may be a legitimate attachment, double check with the sender, and confirm they sent you the file.

- Don’t respond. Even as a joke, don’t do it. By responding to scammers, you demonstrate that your email is valid and they will just send you more. The same goes for SMS text message and call scams. Just hang up and block the caller. If it’s a text message you can copy and forward it to the number 7726 (SPAM), doing so improves your phone carrier’s ability to filter out spam messages.

- Use multi-factor authentication. With two-factor or multi-factor authentication, even if your username and password are compromised via phishing, cybercriminals won’t be able to get around the additional factors of authentication tied to your account.

- Install a good cybersecurity program. Mistakes happen. If you click a bad link or malicious attachment, your cybersecurity program should recognize the threat and shut it down before it can do any damage to your device. Malwarebytes, for example, blocks malicious websites, malvertising, malware, viruses, and ransomware with products for home and business. And for threat protection on your iPhone there’s Malwarebytes for iOS, which blocks pesky scam calls and text messages.

See Also

References

- ↑ Definition - What Does Social Engineering Mean? Webroot

- ↑ Social Engineering Attack Lifecycle Imperva

- ↑ The Why and How of Social Engineering Digital Guardian

- ↑ 6 Types of Social Engineering Attacks Norton

- ↑ Six Key Principles of Social Engineering Wikipedia

- ↑ Famous social Engineering Attacks CSO Online

- ↑ How to protect against social engineering Malwarebytes