Strategic Alliance

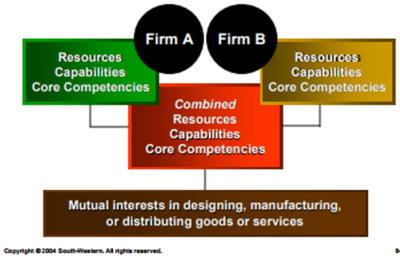

A strategic alliance is a strategic cooperation between two or more organizations, with the aim to achieve a result one of the parties cannot achieve alone.[1]

Booz Allen & Hamilton, a firm of management consultants and an acknowledged expert in the field, defines a strategic alliance as:[2]

A cooperative arrangement between two or more companies in which:

- a common strategy is developed in unison and a win-win attitude is adopted by all parties;

- the relationship is reciprocal, with each partner prepared to share specific strengths with the other, thus lending power to the enterprise;

- a pooling of resources, investment and risks occurs for mutual gain.

source: R. Dennis Middlemist

Strategic alliance agreements are common in the biotechnology sector, where large pharmaceutical organisations sponsor research activities at small, often start-up, research companys. These small organisations often excel in a particular research discipline, but lack the sales, marketing and distribution resources to bring their innovations to market.

Likewise, the large organisations may lack specialized research knowledge in a specific research discipline. A strategic alliance in this setting may take the following form: the pharmaceutical company sponsors research at the small company by either direct cash payments or through a purchase of equity. This may be combined with a revenue sharing agreement that allows the small company to receive a fraction of any proceeds arising from commercialized products that use their research output. By forming a strategic alliance, the organisations share resources to their mutual gain. The 2009 strategic alliance agreement between Monsanto and GrassRoots Biotechnology is a recent example of an alliance between a large company and small research-focused organisation. Monsanto is a globally recognized agriculture company. GrassRoots Biotechnology is a small, research-oriented agricultural biotechnology company. The Monsanto/ Grassroots strategic alliance agreement called for GrassRoots to conduct research on Monsanto’s behalf. Strategic alliances also occur in many other business settings. The strategic alliance between the Dutch airline KLM and the American carrier Northwest Airlines is a famous example of a strategic alliance that allowed two companies to share their routing networks but still remain distinct companies.[3]

Objectives of Strategic Alliance[4]

In strategic alliances, the participants remain separate and do not form a new entity as with joint ventures and some other types of partnerships. They retain autonomy and usually embark on finite projects, rather than an ongoing business relationship. Some of the objectives of a strategic alliance can be:

- To explore the various synergies which may be obtained by working together, particularly in a certain field or industry.

- To undertake joint research projects as may be agreed and consider the joint commercial exploitation of any new technology or products resulting from their joint research.

- To share technical expertise in a certain field or industry to improve research and development results.

- To explore commercial agreements that will be for the mutual benefit of the parties.

Stages of Alliance Formation[5]

- Strategy Development: involves studying the alliance’s feasibility, objectives and rationale,focusing on the major issues and challenges and development of resource strategies.

- Partner Assessment: involves analyzing a potential partner’s strengths and weaknesses, creating strategies for accommodating all partners’ management styles.

- Contract Negotiation: involves determining whether all parties have realistic objectives, defining each partner’s contributions and rewards.

- Alliance Operation: involves addressing senior management’s commitment, finding the caliber of resources devoted to the alliance, linking of budgets and resources with strategic priorities.

- Alliance Termination: involves winding down the alliance, for instance when its objectives have been met or cannot be met.

Forming Strategic Alliances and Partnerships requires careful analysis and planning to ensure mutual benefits. The strategic formulation and implementation guidance offered by the AFI Strategy Framework can aid organizations in identifying and leveraging partnership opportunities to achieve strategic goals.

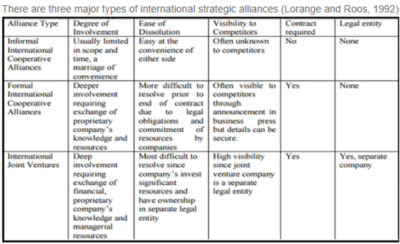

Types of Strategic Alliance[6]

Some types of strategic alliances include:

- Horizontal strategic alliances, which are formed by firms that are active in the same business area. That means that the partners in the alliance used to be competitors and work together In order to improve their position in the market and improve market power compared to other competitors. Research &Development collaborations of enterprises in high-tech markets are typical Horizontal Alliances. Raue & Wieland (2015) describe the example of horizontal alliances between logistics service providers. They argue that such companies can benefit twofold from such an alliance. On the one hand, they can "access tangible resources which are directly exploitable". This includes extending common transportation networks, their warehouse infrastructure and the ability to provide more complex service packages by combining resources. On the other hand, they can "access intangible resources, which are not directly exploitable". This includes know-how and information and, in turn, innovativeness.

- Vertical strategic alliances, which describe the collaboration between a company and its upstream and downstream partners in the Supply Chain, that means a partnership between a company its suppliers and distributors. Vertical Alliances aim at intensifying and improving these relationships and to enlarge the company´s network to be able to offer lower prices. Especially suppliers get involved in product design and distribution decisions. An example would be the close relation between car manufacturers and their suppliers.

Intersectional alliances are partnerships where the involved firms are neither connected by a vertical chain, nor work in the same business area, which means that they normally would not get in touch with each other and have totally different markets and know-how.

- Joint ventures, in which two or more companies decide to form a new company. This new company is then a separate legal entity. The forming companies invest equity and resources in general, like know-how. These new firms can be formed for a finite time, like for a certain project or for a lasting long-term business relationship, while control, revenues and risks are shared according to their capital contribution.

- Equity alliances, which are formed when one company acquires equity stake of another company and vice versa. These shareholdings make the company stakeholders and shareholders of each other. The acquired share of a company is a minor equity share, so that decision power remains at the respective companies. This is also called cross-shareholding and leads to complex network structures, especially when several companies are involved. Companies which are connected this way share profits and common goals, which leads to the fact that the will to competition between these firms is reduced. In addition this makes take-overs by other companies more difficult.

- Non-equity strategic alliances, which cover a wide field of possible cooperation between companies. This can range from close relations between customer and supplier, to outsourcing of certain corporate tasks or licensing, to vast networks in R&D. This cooperation can either be an informal alliance which is not contractually designated, which appears mostly among smaller enterprises, or the alliance can be set by a contract.

Michael Porter and Mark Fuller, founding members of the Monitor Group (now Monitor Deloitte), draw a distinction among types of strategic alliances according to their purposes:

- Technology development alliances, which are alliances with the purpose of improvement in technology and know-how, for example consolidated Research & Development departments, agreements about simultaneous engineering, technology commercialization agreements as well as licensing or joint development agreements.

- Operations and logistics alliances, where partners either share the costs of implementing new manufacturing or production facilities, or utilize already existing infrastructure in foreign countries owned by a local company.

- Marketing, sales and service strategic alliances, in which companies take advantage of the existing marketing and distribution infrastructure of another enterprise in a foreign market to distribute its own products to provide easier access to these markets.

- Multiple activity alliance, which connect several of the described types of alliances. Marketing alliances most often operate as single country alliances, international enterprises use several alliances in each country and technology and development alliances are usually multi-country alliances. These different types and characters can be combined in a multiple activity alliance.

Further kinds of strategic alliances include:

- Cartels: Big companies can cooperate unofficially, to control production and/or prices within a certain market segment or business area and constrain their competition

- Franchising: a franchiser gives the right to use a brand-name and corporate concept to a franchisee who has to pay a fixed amount of money. The franchisor keeps the control over pricing, marketing and corporate decisions in general.

- Licensing: A company pays for the right to use another companies´ technology or production processes.

- Industry Standard Groups: These are groups of normally large enterprises, that try to enforce technical standards according to their own production processes.

- Outsourcing: Production steps that do not belong to the core competencies of a firm are likely to be outsourced, which means that another company is paid to accomplish these tasks.

- Affiliate Marketing: Affiliate marketing is a web-based distribution method where one partner provides the possibility of selling products via its sales channels in exchange of a beforehand defined provision.

Strategic Alliance Criteria[7]

There are five general criteria that differentiate strategic alliances from conventional alliances. An alliance meeting any one of these criteria is strategic and should be managed accordingly.

- Critical to the success of a core business goal or objective: While the most common type of alliance generates revenue through a joint go-to-market approach, not every alliance that produces revenue is strategic. For example, consider the impact on revenue objectives if the relationship were terminated? Clearly, a truly strategic relationship would have a great bearing on the prospects for achieving revenue growth targets. In addition to a single strategic alliance, related groupings of alliances—networks or constellations—may also be critical to a business objective. Sun Microsystems has established a group of integrator alliances that function as an effective marketing channel and drive significant revenues for the company each quarter. This category also includes alliances with high potential, such as alliances that have large but unrealized revenue opportunity. Cost reduction may also be a core business objective of the alliance, particularly among supply-side partners. By investing together in new processes, technologies and standards, alliance partners can obtain substantial cost savings in their internal operations. Again, however, a cost-saving alliance is not truly strategic unless it has an underlying business objective, such as “to achieve an industry-leading cost structure.”

- Critical to the development or maintenance of a core competency or other source of competitive advantage: Another way in which an alliance can prove to be strategic is to play a key role in developing or protecting a firm’s competitive advantage or core competency.Learning alliances are the most common form of competitive/competency strategic alliances. An organization’s need to build incremental skills in an area of importance is often accelerated with the help of an experienced partner. In some cases, the learning objective of the relationship is openly agreed between the partners; however, this is not always the case. Learning alliances work best when:

- 1. The objectives are openly shared

- 2. There is little chance of future competition (such as when the partners are in adjacent industries)

- 3. The cultures of the organizations are similar enough to enable process and methods to be leveraged, and

- 4. The governance structure of the alliances is established to promote learning at the executive, managerial and operational levels.

- Blocks a competitive threat: An alliance can be strategic even when it falls short of establishing a competitive advantage. Consider the case of an alliance that blocks a competitive threat. It is strategic to bring competitive parity to a secondary segment of a market in which the firm competes, when the absence of parity creates a competitive disadvantage in the related primary segments of that market. For example, competing in the high and medium price range of a market with a premium product may leave the firm vulnerable to a low-priced entry. If the firm’s manufacturing processes do not permit the creation of a low-priced product entry, a strategic alliance with a volume partner in an adjacent market can successfully block the competitive threat. Another example of strategic alliances that block competitive threats are the airline alliances that permit route-sharing among carriers. The two primary determinants of customer flight selection are routing and cost. Therefore, the adoption of route-sharing alliances by the airlines blocks the competitive threat of preferential routing in the specific markets in which the airline chooses to compete. In essence, strategic alliances within the airline industry ensure competitive parity with respect to routing and force other factors such as on-time departures and customer service to become the bases for competitive differentiation.

- Creates or maintains strategic choices for the firm:From a longer-term perspective, an alliance that is not fundamental to achieving a business objective today could become critical in the future. For example, in 1984, a U.S. consumer products company needed to expand distribution beyond the Midwestern states. Faced with the prospect of European competition at some point in the future, the firm made a strategic decision to invest in an alliance with a distribution and support services company that had incremental distribution capacity in the U.S. and a similar presence in Europe, rather than invest in expanding its own local distribution capabilities. With the option to expand into European distribution at any point, the firm could work to sew up the U.S. market before expanding too quickly internationally.

- Mitigates a significant risk to the business: When an alliance is driven by intent to mitigate significant risk to an underlying business objective, the nature of the risk and its potential impact on the underlying business objective are the key determinants of whether or not it is truly strategic. Dual sourcing strategies for critical production components or processes are excellent examples of how risk mitigation can become the context for supply-side strategic alliances. As process manufacturing companies advance the yield of their operations, suppliers often collaborate with the manufacturer to ensure their new products fit within its new operations. The benefits of such an alliance are cost savings to the manufacturer and accelerated product development for the supplier. In situations where the supplier’s product is critical to the manufacturer’s operation, it may be necessary for the manufacturer to have strategic alliances with two competing suppliers in order to mitigate such risks as unilateral cost increases or degradation in quality of service.

Historical Overview of Strategic Alliance[8]

Historically, strategic alliance in defined by numerous management theorists. In the decade of 70's, entrepreneurs were more concerned about the performance of the product. Alliances aimed to obtain the best raw materials, the lowest prices, advanced technology and improved market penetration globally. In the decades of 80's, the main objective of companies became merging of the company's position in the sector, using alliances to shape economies of scale and scope. In this period, there was an outburst of alliances. For example, the one between Boeing and a consortium of Japanese companies to build the fuselage of the passenger transport version of the 767; the alliance between Eastman Kodak and Canon, which allowed Canon to produce a line of photocopiers sold under the Kodak brand; an agreement between Toshiba and Motorola to combine their respective technologies in order to produce microprocessors. Harbison and Pekar (1998) stated that during 90's, collapsing barriers between many geographical markets and the distorting of borders between sectors brought the expansion of capabilities and competencies to the centre of attention. It became necessary to forestall one's competitors through a continuous flow of innovations giving recurrent competitive advantage.

source: Civil Service India

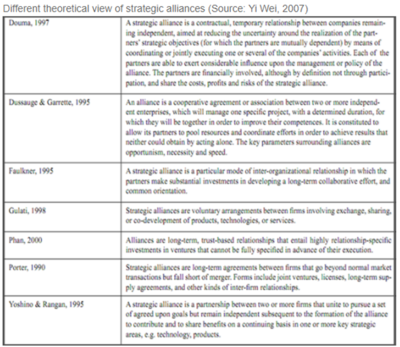

There are numerous theories developed on strategic alliance that concentrate on the reasons why firms enter into closer business relationships. These theories include transaction costs analysis (Williamson,1975,1985), competitive strategy(Porter,1980), resource dependence (Pfeffer and Salancik, 1978; Thompson (1967), political economy (Benson,1975;Stern and Reve,1980), social exchange theory (Anderson and Narus,1984).

Summary of different theories of strategic alliances (Source: Siew-Phaik Loke et.al, 2009)

source: Civil Service India

source: Civil Service India

Benefits of Strategic Alliances[9]

Enterprises that enter into strategic alliance usually expect to benefit in one or more ways. Some of the potential benefits that enterprises could achieve are such as:

- Gaining capabilities: An enterprise may want to produce something or to acquire certain resources that it lacks in the knowledge, technology and expertise. It may need to share those capabilities that the other firms have. Thus, strategic alliance is the opportunity for the enterprise to achieve its objectives in this aspect. Further to that, in later time the enterprise also could then use the newly acquired capabilities by itself and for its own purposes.

- Easier access to target markets: Introducing the product into a new market can be complicated and costly. It may expose the enterprise to several obstacles such as entrench competition, hostile government regulations and additional operating complexity. There are also the risks of opportunity costs and direct financial losses due to improper assessment of the market situations. Choosing a strategic alliance as the entry mode will overcome some of those problems and help reduce the entry cost. For example, an enterprise can license a product to its alliance to widen the market of that particular product.

- Sharing the financial risk: Enterprises can make use of the strategic arrangement to reduce their individual enterprise’s financial risk. For example, when two firms jointly invested with equal share on a project, the greatest potential that each of them stand to loose is only half of the total project cost in case the venture failed.

- Winning the political obstacle: Bringing a product into another country might confront the enterprise with political factors and strict regulations imposed by the national government. Some countries are politically restrictive while some are highly concerned about the influence of foreign firms on their economics that they require foreign enterprises to engage in the joint venture with local firms. In this circumstance, strategic alliance will enable enterprises to penetrate the local markets of the targeted country.

- Achieving synergy and competitive advantage: Synergy and competitive advantage are elements that lead businesses to greater success. An enterprise may not be strong enough to attain these elements by itself, but it might possible by joint efforts with another enterprise. The combination of individual strengths will enable it to compete more effectively and achieve better than if it attempts on its own. For example, to create a favorable brand image in the consumer’s mind is costly and time-consuming. For this reason, an enterprise deciding to introduce its new product may need a strategic arrangement with another enterprise that has a ready image in the market.

Disadvantages of Strategic Alliances[10]

Though, the strategic alliance brings lots of advantages for the partnered firms it has certain loopholes.

- Since each firm maintains its autonomy and has a different way to perform the business operations, there could be a difficulty in coping with each other’s style of performing the business operations.

- There could be a mistrust among the parties when some competitive or proprietary information is required to be shared.

- Often, the firms become so much dependent on each other that they find difficult to operate distinctively and individually at times when they are required to perform as a separate entity.

Risks of Strategic Alliances[11]

Though the arrangement is generally spelled out clearly, the differences in how the businesses operate can cause some struggles. Further, if the alliance requires informing one party of the other party’s proprietary information, there may be a level of distrust within the corresponding leadership. In cases of long-term strategic alliances, the involved parties may become dependent on one another. While the risk is lower if the dependency is experienced by both parties, the risk can increase significantly if the dependence becomes one sided, as this puts an advantage to one side.

See Also

- Strategic Management

- Strategic Alignment Maturity Model

- IT Value Mapping

- Strategic Planning Cycle

- Business Vision

- Strategy

- Business IT Alignment

- Business Strategy

- corporate strategy

- IT Strategy Framework

- IT Capability

- Business Capability

- IT Vision

- e-Business Strategy

- Business IT Alignment

- IT Strategy

- Strategic Alignment

References

- ↑ Definition of Strategic Alliance Peter Simmons

- ↑ Explaining Strategic Alliance Economist

- ↑ Examples of Strategic Alliance Financial Times

- ↑ What are the Objectives of Strategic Alliance? Global Negotiator

- ↑ The Stages of Alliance Formation Criss Ramirez

- ↑ Different Types of Strategic Alliance Wikipedia

- ↑ The five criteria of a strategic alliance Ivey Business Journal

- ↑ Historical Overview of Strategic Alliance CivilServiceIndia

- ↑ Benefits of Strategic Alliances Ahmed Karam

- ↑ Disadvantages of Strategic Alliances Business Jargons

- ↑ Risks of Strategic Alliances Investopedia

Further Reading

- The Interorganizational Learning Dilemma: Collective Knowledge Development in Strategic Alliances Rikard Larsson et al.

- Strategic Alliance Structuring: A Game Theoretic and Transaction Cost Examination of Interfirm Cooperation Arvind Parkhe

- Resource and Risk Management in the Strategic Alliance Making Process T. K. Das, Bing-Sheng Teng

- The Makings Of A Great Strategic Alliance Partnership Forbes

- An Introduction to Strategic Alliance Management Jeff Shuman and Jan Twombly