Strategy

What is Strategy?

Strategy is an approach to apply capability and resources to achieve an objective(s). Strategy is formulated and executed factoring in the environment, landscape, players or actors, and forces affecting the achievement of the said objective(s). Strategic position is the relative placement of each player in the landscape and can provide an advantage or disadvantage in the achievement of the objective(s)

- Approach: Strategy concerns itself with "how" not the steps or process

- Capability: A player's core competency is a critical factor driving the selection of an approach

- Resources: Resources are limited by definition and include, but are not limited to, materials, tools, relationships, and time.

- Achieve: Provable results are critical to strategy. Measurement of metrics is a key indicator of progress toward an objective and proof of its realization.

- Objective: Whether taking a hill or delivering a higher share price must be achieved at the lowest cost and risk.

- Sustainable: Another critical aspect of the strategy is that its gains must be sustainable. This is helpful in defining an objective and measuring its achievement.

- Feedback: An effective strategy has built-in mechanisms to ingest real-time input of environmental and landscape information and adapt to changing circumstances.

Simply put, in business, strategy is the most efficient approach to value. The steps, their sequence, and the timeline used to execute a strategy are called a plan. The winning formula can be encapsulated into a strategic framework - essential components and their relationships - and a business model - how an entity creates and exchanges value.[1]

What Strategy Does and Does Not Do

Strategy is an approach to solving a problem. Strategy comprises two key components: guiding principles and algorithm

- Strategy is abstract

- Strategy DOES NOT specify the solution

- Strategy DOES NOT specify the steps of the solution

- Strategy requires analysis that picks from the different alternatives or options available to approach a given problem. A problem that lends itself to one and only one solution has, by definition, no use for a strategy.

- Strategy requires structure so results can be repeated.

However, strategy does not have to be formal or documented. By definition, a solution to a problem has a strategy albeit one that may not have the required structure, analysis, or documentation.

- Strategy involves optimization - getting to the most value with the least cost and risk.

- Strategy is iterative - multiple learn-and-do cycles that result in better outcomes over time.

- Strategy is measured on the value delivered with the least amount of cost and risk i.e. a strategic outcome is the sum total of value, cost, and risk. Therefore, a strategy that uses more money to deliver the same value but at lower risk might be preferred over one that uses less money but increases risk.

- Strategy takes a long-term view of the problem whereas tactics take a short-term view.

- Strategy can be broken into parts or sub-strategies - each building up to the desired outcome but still an abstraction lacking the specificity or detail of a solution, process, or plan.

- Strategy answers the question: How will you solve this problem without specifying the steps? Strategy can be an idea or a design or a method or a blueprint to solve a problem, accomplish a task, or achieve an objective. Strategy is often confused with a plan - a plan details the steps or process to implement the solution. A plan brings specificity to a strategy. Vision visualizes the state after the solution is implemented. Mission specifies the objective of the solution.[2]

Other Definitions of Strategy

Business Dictionary defines Strategy as a "method or plan chosen to bring about a desired future, such as achievement of a goal or solution to a problem." It also defines Strategy as "The art and science of planning and marshaling resources for their most efficient and effective use." The term is derived from the Greek word for generalship or leading an army.[3]

Strategy is all about gaining or at least attempting to gain, a position of advantage over adversaries or competitors. Being forward-looking there is always uncertainty and risk associated with deciding strategy. The question ‘what is strategy?’ therefore also implies a set of strategic options from which one chooses a course of action to achieve an advantage. Strategy is more about a set of options or "strategic choices" than a fixed plan.[4]

The strategic management discipline relies on different definitions of strategy for researchers and practitioners. Henry Mintzberg, an expert in the management discipline, developed five different meanings of strategy (5Ps) to help others in the application of strategy. According to Mintzberg, the different approaches to defining strategy are:

- Strategy as a plan: Strategy can be described as a plan—A course of action that is meticulously intended to deal with a specific situation. Going by this definition, strategy essentially has two characteristics: it is developed in advance of the action to which it applies, and it is developed purposefully and consciously.

- Strategy as a pattern: Mintzberg presented the definition of strategy as a carefully intended course of action whose resulting behavior can be identified. Hence, strategy is a pattern—particularly, a pattern within a series of actions. A corporate strategy, for example, may mean a pattern of actions that an organization undertakes for it to realize its goals.

- Strategy as a position: The term strategy being the position of an organization means placing the organization in the environment that best describes its goals and objectives. This, therefore, creates a mediating force between the organization and the environment. The environment, in this case, represents the internal and external views. A position can imply offering differentiated products, a niche, or employing unique competencies in the market to gain Competitive Advantage.

- Strategy as a ploy: According to Mintzberg, an organization gaining a competitive advantage by plotting to discourage, disrupt, influence, or even deter a rivaling organization can be termed as a strategy. In this case, a strategy becomes a ploy whereby it is a maneuver taken to get the better of a competitor.

- Strategy as a perspective: Strategy as a perspective is a look inside the organization, and indeed is how the collective strategist portrays an organization’s entrenched way of perceiving the world. For instance, some organizations are aggressive trendsetters, developing new markets and building new technologies; others perceive the universe as stable and set, and therefore become comfortable in their established markets, constructing protective ammunition around themselves. Understanding and implementing each element of strategy can help an organization develop a practical and robust business strategy.[5]

Harvard University’s Professor Michael E Porter addressing the question ‘What is strategy?’ in a classic article by that name in 1992 defined strategy by separating it from operational efficiency and effectiveness, and putting it in terms of market positioning. Porter asserts that operational effectiveness (OE) means performing similar activities better than rivals do. Better means more efficient, faster, and cheaper. It is necessary to achieve superior profitability. However, while OE is necessary, it is not sufficient. Operational effectiveness by itself is not a strategy. It is just the price of admission to the game so to speak. An enterprise needs to establish a difference that it can sustain. Strategy is about differentiating your organization from competitor enterprises. What is strategy? It is about being different in the choice of a different mix of activities to provide a product or service. Strategic positions can emerge from three distinct sources, which serve as a basis for positioning:

- Variety-based positioning: A company can specialize in a subset of an industry’s product (e.g. sell office chairs only, not office furniture in general)

- Needs-based positioning: A company can try to serve more needs of a target group than rivals (e.g. not only sell office chairs but other office furniture and perhaps business equipment as well)

- Access-based positioning: A company can segment customers who are accessible in different ways (e.g. only sell chairs in central business districts of major cities).

Trade-offs are required when two activities are incompatible (e.g. you sell low-cost chairs while offering highly customized office design and fit-out services. Companies have to make sure that their activities are coherent. This implies refraining from certain activities. Strategy is about choosing what not to do, as much as it is about choosing what things to do. Another important aspect is how an organization combines activities. By creating a fit among activities, competitors find it harder to imitate the configuration of activities and resources that make up the value delivering business model. Obviously, the strength of an enterprise can result from a combination of activities. We can think of themes (e.g. low-cost), that span across activities. Strategic fit is fundamental not only to the competitive advantage but also to the sustainability of that advantage. The biggest threat to strategy is the desire to grow. Trade-offs set by the strategy seem to limit growth. Trying to compete at numerous levels at once creates confusion and undermines organizational motivation and focus. The solution is to grow by deepening the strategic position. This means making the activities even more distinctive, strengthening fit, and communicating the strategy to new customers.[6]

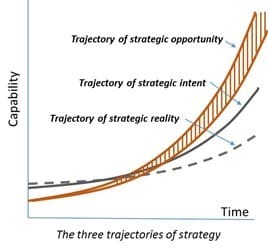

The Purpose and Trajectory of Strategy[7]

The purpose of strategy is to close the gap between an organization’s current reality and that which is strategically possible. As the following graph depicts, the strategic trajectory for a business should land somewhere between reality and opportunity. Consider the following three trajectories:

- Trajectory of strategic opportunity – the trajectory your organization could pursue if it faced no constraints.

- Trajectory of strategic reality – the trajectory your organization is currently taking.

- Trajectory of strategic intent – the trajectory your organization has chosen to take based upon an understanding of the trajectory of strategic reality and trajectory of strategic possibility.

In the case of strategic intent, it is where your organization has determined the goal or level of Contract Optimization and how long it expects to get there. That is determined by assessing budget, time, and resources for the trajectory.

Components of Strategy[8]

Professor Richard P. Rumelt described strategy as a type of problem-solving in 2011. He wrote that good strategy has an underlying structure he called a kernel. The kernel has three parts:

1) A diagnosis that defines or explains the nature of the challenge;

2) A guiding policy for dealing with the challenge; and

3) Coherent actions designed to carry out the guiding policy.

President Kennedy illustrated these three elements of strategy in his Cuban Missile Crisis Address to the Nation on 22 October 1962:

- Diagnosis: "This Government, as promised, has maintained the closest surveillance of the Soviet military buildup on the island of Cuba. Within the past week, unmistakable evidence has established the fact that a series of offensive missile sites is now in preparation on that imprisoned island. The purpose of these bases can be none other than to provide a nuclear strike capability against the Western Hemisphere."

- Guiding Policy: "Our unswerving objective, therefore, must be to prevent the use of these missiles against this or any other country, and to secure their withdrawal or elimination from the Western Hemisphere."

- Action Plans: First among seven numbered steps was the following: "To halt this offensive buildup a strict quarantine on all offensive military equipment under shipment to Cuba is being initiated. All ships of any kind bound for Cuba from whatever nation or port will, if found to contain cargoes of offensive weapons, be turned back."

Rumelt wrote in 2011 that three important aspects of strategy include "premeditation, the anticipation of others' behavior, and the purposeful design of coordinated actions." He described strategy as solving a design problem, with trade-offs among various elements that must be arranged, adjusted, and coordinated, rather than a plan or choice.

Levels of Strategy[9]

Strategy may operate at different levels of an organization – corporate level, business level, and functional level. The strategy changes based on the levels of strategy.

- Corporate Level Strategy: Corporate level strategy occupies the highest level of strategic decision-making and covers actions dealing with the objective of the firm, acquisition, and allocation of resources, and coordination of strategies of various SBUs for optimal performance. The top management of the organization makes such decisions. The nature of strategic decisions tends to be value-oriented, conceptual, and less concrete than decisions at the business or functional level.

- Business-Level Strategy: Business level strategy is – applicable in those organizations, which have different businesses-and each business is treated as strategic business unit (SBU). The fundamental concept in SBU is to identify the discrete independent product/market segments served by an organization. Since each product/market segment has a distinct environment, an SBU is created for each such segment. For example, Reliance Industries Limited operates in textile fabrics, yarns, fibers, and a variety of petrochemical products. For each product group, the nature of the market in terms of customers, competition, and marketing channels differs. Therefore, it requires different strategies for its different product groups. Thus, where SBU concept is applied, each SBU sets its own strategies to make the best use of its resources (its strategic advantages) given the environment it faces. At such a level, strategy is a comprehensive plan providing objectives for SBUs, allocation of resources among functional areas, and coordination between them for making an optimal contributions to the achievement of corporate-level objectives. Such strategies operate within the overall strategies of the organization. The corporate strategy sets the long-term objectives of the firm and the broad constraints and policies within which an SBU operates. The corporate level will help the SBU define its scope of operations and also limit or enhance the SBUs operations by the resources the corporate level assigns to it. There is a difference between corporate-level and business-level strategies. For example, in an organization of any size or diversity, corporate strategy usually applies to the whole enterprise, while business strategy, less comprehensive, defines the choice of product or service and market of individual business within the firm. In other words, business strategy relates to the ‘how’ and corporate strategy to the ‘what’. Corporate strategy defines the business in which a company will compete preferably in a way that focuses resources to convert distinctive competence into a competitive advantage. Corporate strategy is not the sum total of business strategies of the corporation but it deals with different subject matters. While the corporation is concerned with and has an impact on business strategy, the former is concerned with the shape and balancing of growth and renewal rather than in-market execution.

- Functional-Level Strategy: Functional strategy, as suggested by the title, relates to a single functional operation and the activities involved therein. Decisions at this level within the organization are often described as tactical. Such decisions are guided and constrained by some overall strategic considerations. Functional strategy deals with relatively restricted plans providing objectives for a specific function, allocation of resources among different operations within that functional area, and coordination between them for optimal contribution to the achievement of the SBU and corporate-level objectives. Below the functional-level strategy, there may be operations-level strategies as each function may be divided into several sub-functions. For example, marketing strategy, a functional strategy, can be subdivided into promotion, sales, distribution, and pricing strategies with each sub-function strategy contributing to the functional strategy.

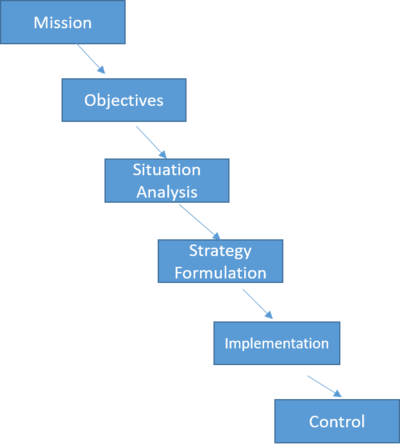

Strategic Planning Process (See Figure 1.)[10]

In the 1970's, many large firms adopted a formalized top-down strategic planning model. Under this model, strategic planning became a deliberate process in which top executives periodically would formulate the firm's strategy, then communicate it down the organization for implementation.

- Mission: A company's mission is its reason for being. The mission often is expressed in the form of a mission statement, which conveys a sense of purpose to employees and projects a company image to customers. In the strategy formulation process, the mission statementt sets the mood of where the company should go.

- Objectives: Objectives are concrete goals that the organization seeks to reach, for example, an earnings growth target. The objectives should be challenging but achievable. They also should be measurable so that the company can monitor its progress and make corrections as needed.

- Situation Analysis: Once the firm has specified its objectives, it begins with its current situation to devise a strategic plan to reach those objectives. Changes in the external environment often present new opportunities and new ways to reach objectives. An environmental scan is performed to identify the available opportunities. The firm also must know its own capabilities and limitations in order to select the opportunities that it can pursue with a higher probability of success. The situation analysis, therefore, involves an analysis of both the external and internal environment. The external environment has two aspects: the macro-environment that affects all firms and the micro-environment that affects only the firms in a particular industry. The macro-environmental analysis includes political, economic, social, and technological factors and sometimes is referred to as a PEST analysis. An important aspect of the micro-environmental analysis is the industry in which the firm operates or is considering operating. Michael Porter devised a five-forces framework that is useful for industry analysis. Porter's 5 forces include barriers to entry, customers, suppliers, substitute products, and rivalry among competing firms. The internal analysis considers the situation within the firm itself, such as:

- Company culture

- Company image

- Organizational structure

- Key staff

- Access to natural resources

- Position on the experience curve

- Operational efficiency

- Operational capacity

- Brand awareness

- Market share

- Financial resources

- Exclusive contracts

- Patents and trade secrets

Situation analysis can generate a large amount of information, much of which is not particularly relevant to strategy formulation. To make the information more manageable, it sometimes is useful to categorize the internal factors of the firm as strengths and weaknesses, and the external environmental factors as opportunities and threats. Such analysis often is referred to as a SWOT Analysis.

- Strategy Formulation: Once a clear picture of the firm and its environment is in hand, specific strategic alternatives can be developed. While different firms have different alternatives depending on their situation, there also exist generic strategies that can be applied across a wide range of firms. Michael Porter identified cost leadership, differentiation, and focus as three generic strategies that may be considered when defining strategic alternatives. Porter advised against implementing a combination of these strategies for a given product; rather, he argued that only one of the generic strategy alternatives should be pursued.

- Implementation: The strategy likely will be expressed in high-level conceptual terms and priorities. For effective implementation, it needs to be translated into more detailed policies that can be understood at the functional level of the organization. The expression of the strategy in terms of functional policies also serves to highlight any practical issues that might not have been visible at a higher level. The strategy should be translated into specific policies for functional areas such as:

- Marketing

- Research and development

- Procurement

- Production

- Human Resources

- Information systems

In addition to developing functional policies, the implementation phase involves identifying the required resources and putting into place the necessary organizational changes.

- Control:Once implemented, the results of the strategy need to be measured and evaluated, with changes made as required to keep the plan on track. Control systems should be developed and implemented to facilitate this monitoring. Standards of performance are set, the actual performance measured, and appropriate action is taken to ensure success.

The strategic management process is dynamic and continuous. A change in one component can necessitate a change in the entire strategy. As such, the process must be repeated frequently in order to adapt the strategy to environmental changes. Throughout the process, the firm may need to cycle back to a previous stage and make adjustments.

The Strategic Planning Process

Figure 1. source: CIO Index

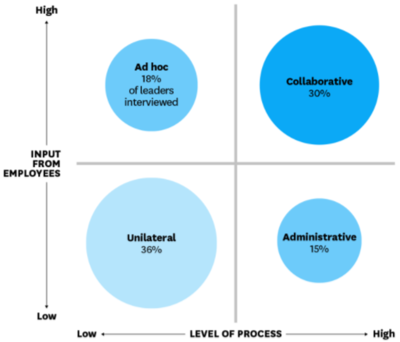

Approaches to Strategic Decision Making (See Figure 2).[11]

Companies’ processes differed from each other in two ways. The first was whether a firm uses a high or low level of process to make strategic decisions. That is, does it have recurring routines for discussing strategy, triggering strategic changes, and reviewing those changes? The second was the amount of input from other employees that the leader considers while making a strategic decision. This factor focuses on employee involvement in decision-making, not simply attendance at meetings or post-decision communication. These two factors can exist in any pairing, and based on our interviews, firms populate all boxes, which gives us four distinct archetypes of strategic decision-making.

- Unilateral firms are both low process and low input. They tend to have a top-down leader who makes decisions alone. During our interviews, these individuals often had difficulty explaining their decision-making process and the role other employees played. Interestingly, these interviewees had two different types of attitudes: Some disliked their process and admitted that they should do things differently, while others seemed very confident with how they made decisions. A potential benefit for Unilateral firms is that leaders can make decisions quickly, without the constraints of process complexity and debate. However, the bad news is that lacking checks and balances, Unilateral firms can make bad decisions fast. Moreover, speed is not a sure thing in a Unilateral firm: If the top-down leader chooses to procrastinate on a tough decision, no process is there to force timely action.

- Ad Hoc firms are low process and high input. These firms do not have a codified, recurring process that they follow every time they make a strategic change. But when a change needs to be made, the leader pulls the team together to take action. The exact steps the firm follows and the exact people in the room change from one decision to the next. The benefit of data collection and documentation that accompanies this extensive process. If Administrative firms are smart, they can leverage this information to improve future decision-making. But, similar to Unilateral firms, the low level of input can result in bad decisions if leaders do not consider key information or opinions. In fact, this risk can be especially grave in Administrative firms because the detailed process and the sheer quantity of information gathered can act as theater, masking the lack of broad input from internal and external stakeholders.

- Collaborative firms are both high process and high input. These firms have the rigorous process of an Administrative firm, but also the engaged employees of an Ad Hoc firm. During interviews, these leaders showed strong consistency across different types of decisions and could clearly articulate how employees added value during the process. The detailed process ensures that the leaders don’t miss any steps. The frequent input ensures that they don’t miss any information. However, the inflexible system can potentially slow down decision-making and prevent firms from acting on time-sensitive opportunities. For example, Collaborative firms may inadvertently include irrelevant parties in strategy discussions or spend too much time achieving consensus among the participants in order to maintain engagement.

Four Approaches to Strategic Decision Making

Figure 2. source: HBR

Strategy Implementation[12]

Strategy implementation is the translation of chosen strategy into organizational action so as to achieve strategic goals and objectives. Strategy implementation is also defined as the manner in which an organization should develop, utilize, and amalgamate organizational structure, control systems, and culture to follow strategies that lead to competitive advantage and better performance. Organizational structure allocates special value developing tasks and roles to the employees and states how these tasks and roles can be correlated so as maximize efficiency, quality, and customer satisfaction-the pillars of competitive advantage. But, the organizational structure is not sufficient in itself to motivate the employees. An organizational control system is also required. This control system equips managers with motivational incentives for employees as well as feedback on employees and organizational performance. Organizational culture refers to the specialized collection of values, attitudes, norms, and beliefs shared by organizational members and groups. The following are the main steps in implementing a strategy:

- Developing an organization having the potential of carrying out strategy successfully.

- Disbursement of abundant resources to strategy-essential activities.

- Creating strategy-encouraging policies.

- Employing best policies and programs for constant improvement.

- Linking reward structure to the accomplishment of results.

- Making use of strategic leadership.

Excellently formulated strategies will fail if they are not properly implemented. Also, it is essential to note that strategy implementation is not possible unless there is a stability between strategy and each organizational dimension such as organizational structure, reward structure, resource-allocation process, etc. Strategy implementation poses a threat to many managers and employees in an organization. New power relationships are predicted and achieved. New groups (formal as well as informal) are formed whose values, attitudes, beliefs, and concerns may not be known. With the change in power and status roles, the managers and employees may employ confrontational behavior.

Why Strategy Fails[13]

There are three key reason strategy fails. Do you recognize any of these?

1. It’s incorrectly formulated: Many times senior leadership or marketing teams approach their strategy planning with the attitude that it’s a tedious but necessary evil ostensibly undertaken in order to tick a box. If your approach to strategy is about ticking the box, there are two things that may happen: Firstly, it’s probably going to end up in the CEO’s bottom drawer. Secondly, that’s where it belongs. Because a strategy designed to tick a box will be both worthless and wrong. The formulation of strategy must be taken seriously, a commitment made by each member of the executive team. It must be a collaborative effort that begins with creating a vision for the organization with strategies that align with that vision as well as the external environment and the organization’s capabilities.

2. Organisational structure and processes don’t align with the strategy: Frequently a strategy is formulated, without consideration of operational execution. Too often a strategy is gridlocked as soon as it meets execution because an organization’s structure and processes hinder the execution of the strategy. This may be due to organization design, human resource or skill limitations, internal capabilities, technological structures, and systems. If the structure and processes are not aligned with the strategy then the strategy has failed before it’s even started. Strategy formulation and execution must be part of the same process.

3. Staff and stakeholders don’t engage: This is the key reason strategy fails – because the executive team has failed to engage the people that are critical to the execution of the strategy – the staff and stakeholders. When a strategy is formulated in isolation by the executive team, when they fail to engage staff and critical stakeholders in the formulation but expect that they’ll execute it upon command there’s generally only one response - resistance. When staff or stakeholders resist executing your strategy it’s all over – your strategy has failed. The most important factor in strategy development is its execution. That means engaging all those you depend on for the delivery of the strategy – and engaging them early. When people feel that they are a part of the process, that they understand the vision, and acknowledge the need for change, and when they see their role in it, they engage. If they don’t your strategy is toast. So make this the most important factor in strategy creation and execution.

See Also

- Strategic Alignment

- Strategic Architecture

- Strategic Analysis

- Strategic Change

- Strategic Goal

- Strategic Influence

- Strategic Leadership

- Strategic Risk Management

- Strategy Change Cycle

- Strategy Dynamics

- Strategy Execution

- Strategy Maps

- Strategy Markup Language (StratML)

- Strategy Process Steps

- Strategy Visualization

- Strategic Altitude

- Strategic Fit

- Strategic Grid for IT

- Strategic Human Resource Management (SHRM)

- Strategic Infliction Point

- Strategic Initiatives

- Strategic Stakeholder

- Strategic Stakeholder Management

- Strategic Synergy

- Strategic Themes

- Strategic Thrusts

- Strategic Window

- Adaptive Strategy

References

- ↑ What Does Strategy Mean? by Sourabh Hajela

- ↑ Business Strategy Knowledge Base on CIO Index

- ↑ Definition - What does Strategy Mean?

- ↑ What is Strategy

- ↑ Mizberg's Definition of Strategy (5Ps)

- ↑ Porter's definition of Strategy

- ↑ What is the purpose of Strategy?

- ↑ Components of Strategy

- ↑ The Three Levels of Strategy

- ↑ The Strategic Planning Process

- ↑ hbr.org The Different Approaches Firms Use to Set Strategy

- ↑ Strategy Implementation - Meaning and Steps in Implementing a Strategy

- ↑ The three reasons strategy fails

Further Reading

- What is Strategy? -Harvard Business Review

- What is Strategy Again? -HBR

- Five Steps to a Strategic Plan -Forbes

- Strategic Planning Process - PowerPoint Presentation -Randy Taylor

- Five Reasons Most Companies Fail at Strategy Execution -indead

- Porter or Mintzberg: Whose View of Strategy Is the Most Relevant Today? -Karl Moore